Image by Arielle Fragassi, via Flickr Commons

In May of 1967,” writes Patrick Iber at The Awl, “a former CIA officer named Tom Braden published a confession in the Saturday Evening Post under the headline, ‘I’m glad the CIA is ‘immoral.’” With the hard-boiled tone one might expect from a spy, but the candor one may not, Braden revealed the Agency’s funding and support of all kinds of individuals and activities, including, perhaps most controversially, in the arts. Against objections that so many artists and writers were socialists, Braden writes, “in much of Europe in the 1950’s [socialists] were about the only people who gave a damn about fighting Communism.”

Whatever truth there is to the statement, its seeming wisdom has popped up again in a recent Washington Post op-ed by Sonny Bunch, editor and film critic of the conservative Washington Free Beacon. The CIA should once again fund “a culture war against communism,” Bunch argues. The export (to China) he offers as an example? Boots Riley’s hip, anti-neoliberal, satirical film Sorry to Bother You, a movie made by a self-described Communist.

Proud declarations in support of CIA funding for “socialists” may seem to take the sting out of moral outrage over covert cultural tactics. But they fail to answer the question: what is their effect on artists themselves, and on intellectual culture more generally? The answer has been ventured by writers like Joel Whitney, whose book Finks looks deeply into the relationship between dozens of famed mid-century writers and literary magazines—especially The Paris Review—and the agency best known for toppling elected governments abroad.

In an interview with The Nation, Whitney calls the CIA’s containment strategies “the inversion of influence. It’s the instrumentalization of writing.… It’s the feeling of fear dictating the rules of culture, and, of course, therefore, of journalism.” According to Eric Bennett, writing at The Chronicle of Higher Education and in his book Workshops of Empire, the Agency instrumentalized not only the literary publishing world, but also the institution that became its primary training ground, the writing program at the University of Iowa.

The Iowa Writer’s Workshop “emerged in the 1930s and powerfully influenced the creative-writing programs that followed,” Bennett explains. “More than half of the second-wave programs, about 50 of which appeared by 1970, were founded by Iowa graduates.” The program “attained national eminence by capitalizing on the fears and hopes of the Cold War”—at first through its director, self-appointed cold warrior Paul Engle, with funding from CIA front groups, the Rockefeller Foundation, and major corporations. (Kurt Vonnegut, an Iowa alum, described Engle as “a hayseed clown, a foxy grandpa, a terrific promoter, who, if you listened closely, talks like a man with a paper asshole.”)

Under Engle writers like Raymond Carver, Flannery O’Connor, Robert Lowell, and John Berryman went through the program. In the literary world, its dominance is at times lamented for the imposition of a narrow range of styles on American writing. And many a writer has felt shut out of the publishing world and its coteries of MFA program alums. When it comes to certain kinds of writing at least, some of them may be right—the system has been informally rigged in ways that date back to a time when the CIA and conservative funders approved and sponsored the high modernist fiction beloved by the New Critics, witty realism akin to F. Scott Fitzgerald’s (and later John Cheever), and magical realism (part of the agency’s attempt to control Latin American literary culture.)

These categories, it so happens, roughly correspond to those Bennett identifies as acceptable in his experience at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, and to the writing one finds filling the pages of The Best American Short Stories annual anthologies and the fiction section of The New Yorker and The Paris Review. (Exceptions often follow the path of James Baldwin, who refused to work with the agency, and whom Paris Review co-founder and CIA agent Peter Matthiessen subsequently derided as “polemical.”)

Bennett’s personal experiences are merely anecdotal, but his history of the relationships between the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, the explosion of MFA programs in the last 40 years under its influence, and the CIA and other groups’ active sponsorship are well-researched and substantiated. What he finds, as Timothy Aubry summarizes at The New York Times, is that “writing programs during the postwar period” imposed a discipline instituted by Engle, “teaching aspiring authors certain rules of propriety.”

“Good literature, students learned, contains ‘sensations, not doctrines; experiences, not dogmas; memories, not philosophies.’” These rules have become so embedded in the aesthetic canons that govern literary fiction that they almost go without question, even if we encounter thousands of examples in history that break them and still manage to meet the bar of “good literature.” What is meant by the phrase is a kind of currency—literature that will be supported, published, marketed, and celebrated. Much of it is very good, and much happens to have sufficiently satisfied the gatekeepers’ requirements.

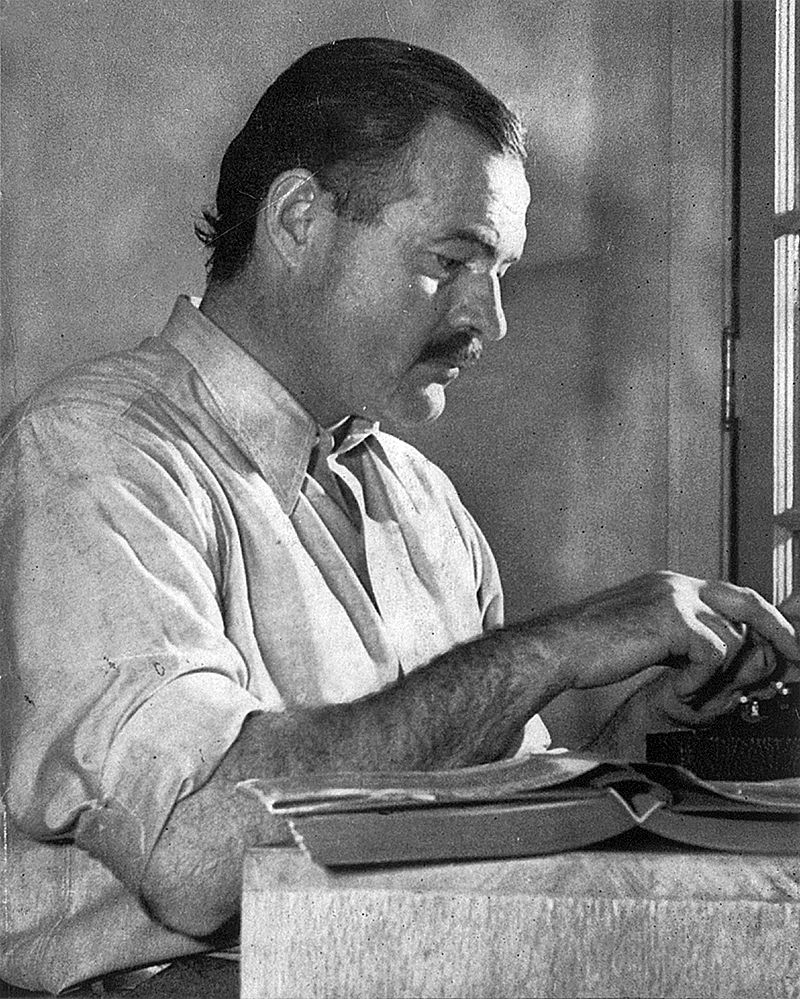

In a reductive, but interesting analogy, Motherboard’s Brian Merchant describes “the American MFA system, spearheaded by the infamous Iowa Writers’ Workshop” as a “content farm” first designed to optimize for “the spread of anti-Communist propaganda through highbrow literature.” Its algorithm: “More Hemingway, less Dos Passos.” As Aubry notes, quoting from Bennett’s book:

Frank Conroy, Engle’s longest-serving successor, who taught Bennett, “wanted literary craft to be a pyramid.” At the base was syntax and grammar, or “Meaning, Sense, Clarity,” and the higher levels tapered off into abstraction. “Then came character, then metaphor … everything above metaphor Conroy referred to as ‘the fancy stuff.’ At the top was symbolism, the fanciest of all. You worked from the broad and basic to the rarefied and abstract.”

The direct influence of the CIA on the country’s preeminent literary institutions may have waned, or faded entirely, who can say—and in any case, the institutions Whitney and Bennett write about have less cultural valence than they once did. But even so, we can see the effect on American creative writing, which continues to occupy a fairly narrow range and show some hostility to work deemed too abstract, argumentative, experimental, or “postmodern.” One result may be that writers who want to get funded and published have to conform to rules designed to co-opt and corral literary writing.

Related Content:

How the CIA Secretly Funded Abstract Expressionism During the Cold War

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness