What do you see when you read the work of Edgar Allan Poe? The great age of the illustrated book is far behind us. Aside from cover designs, most modern editions of Poe’s work circulate in text-only form. That’s just fine, of course. Readers should be trusted to use their imaginations, and who can forget indelible descriptions like “The Tell-Tale Heart”’s “eye of a vulture—a pale, blue eye, with a film over it”? We need no picture book to make that image come alive.

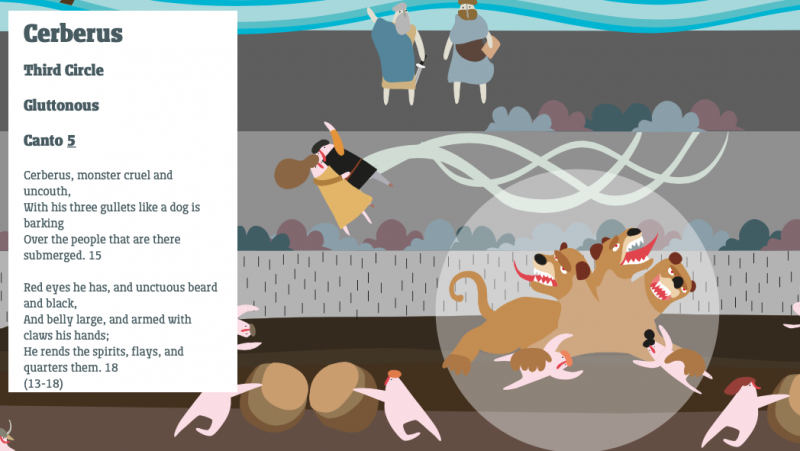

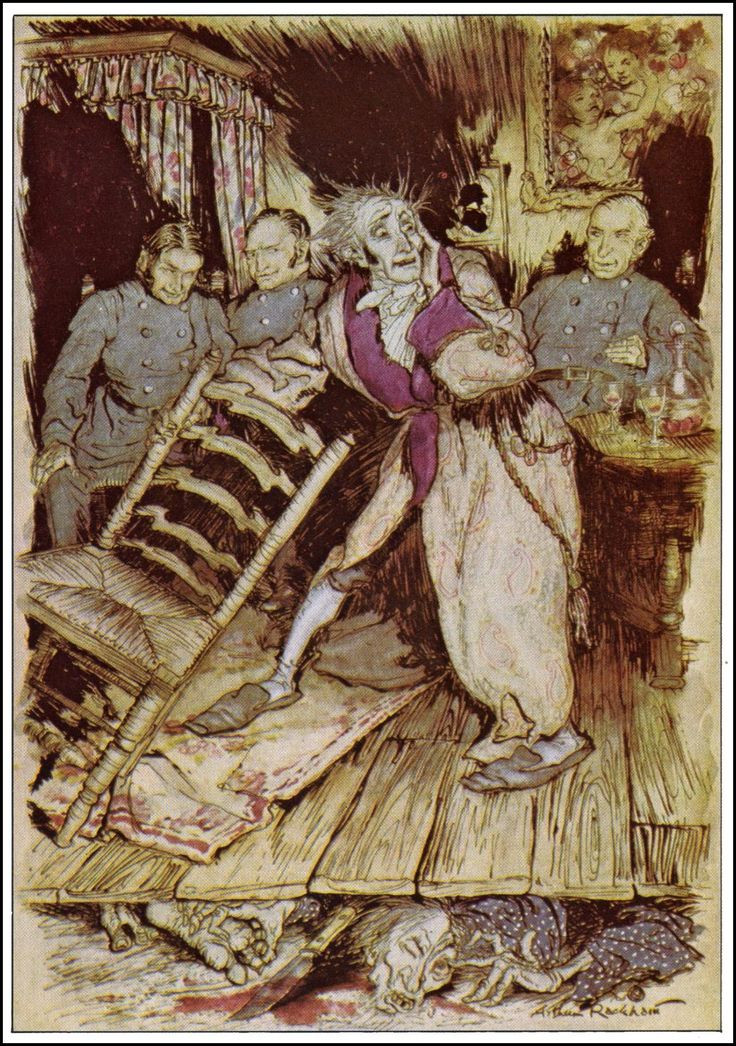

Yet, when we first discover the many illustrated editions of Poe published in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, we might wonder how we ever did without them. A copy of Tales of Mystery and Imagination illustrated by Arthur Rackham in 1935 (above) served as my first introduction to this rich body of work.

Known also for his editions of Peter Pan, The Wind in the Willows, Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and Alice in Wonderland, Rackham’s “signature watercolor technique” was “always in high demand,” Sadie Stein writes at The Paris Review.

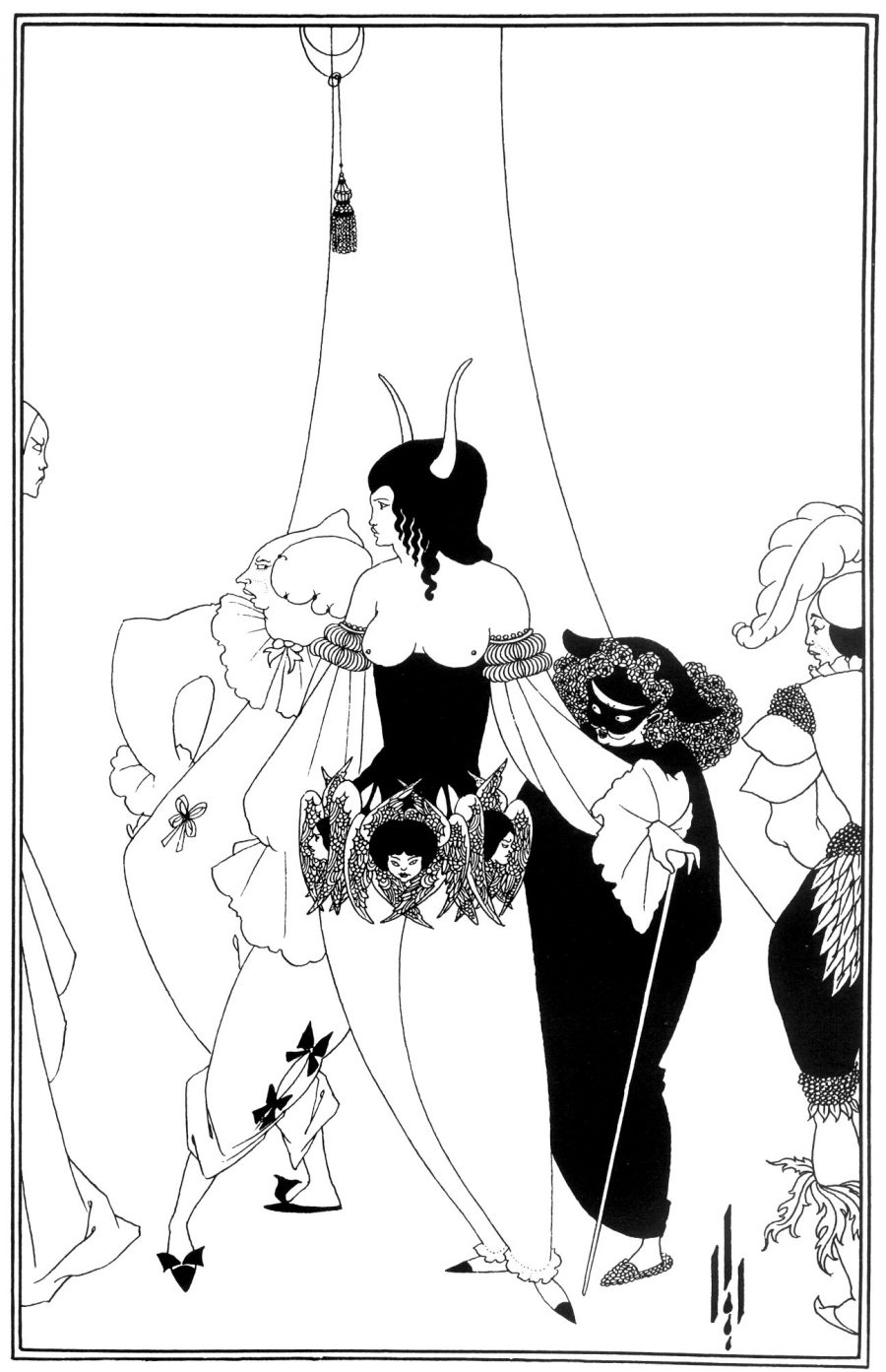

Sometime later, I came across the 1894 Symbolist illustrations of Aubrey Beardsley, and for a while, when Poe came to mind so too did Beardsley’s sensually creepy prints, influenced by Japanese woodcuts and Art Nouveau posters. His stylized take on Poe, notes Print magazine, offers “a very different aesthetic from the works of his predecessors.” Most prominent among those earlier illustrators was the hugely prolific Gustave Doré, whose classical renderings of the Divine Comedy and Don Quixote may have few equals in a field crowded with illustrated editions of those books.

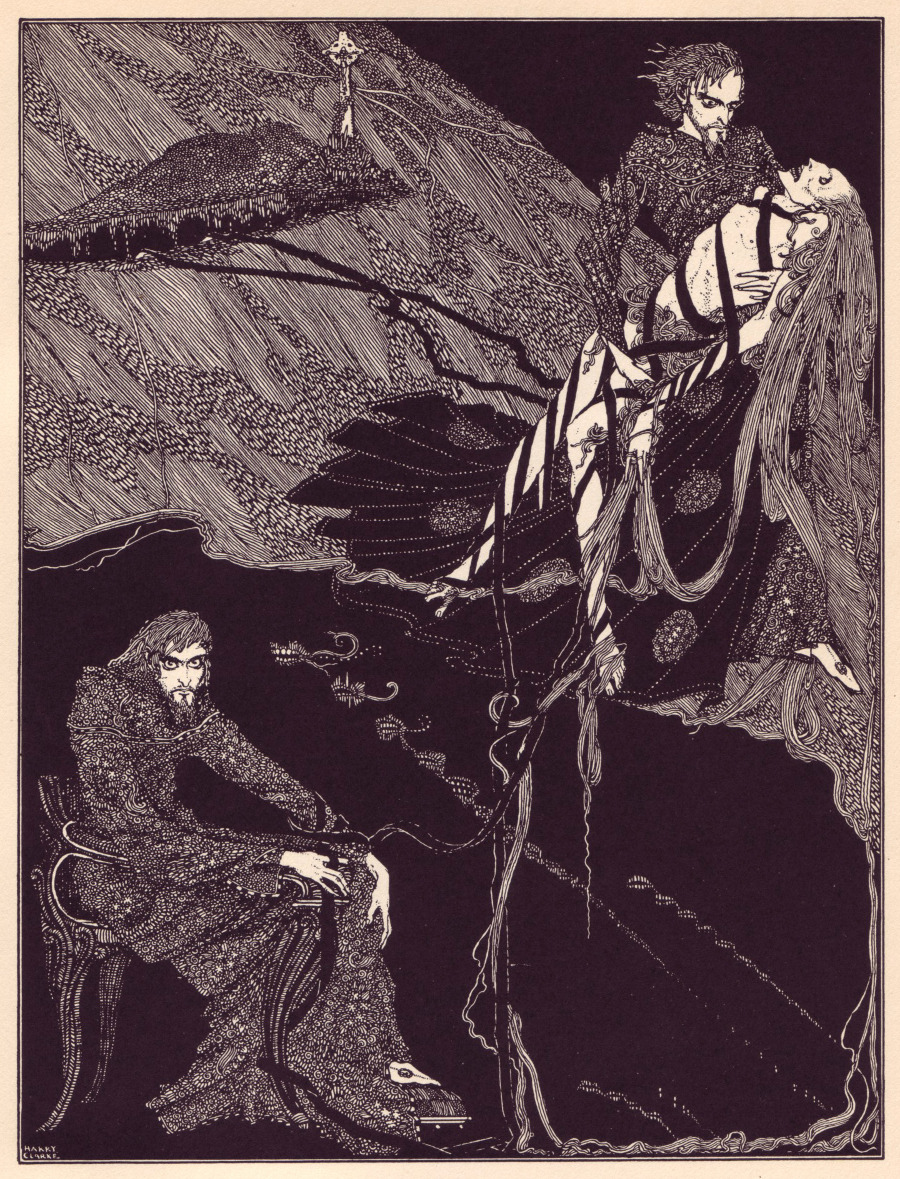

But for me, there’s something lacking, in the 26 steel engravings Doré made for an 1884 edition of Poe’s “The Raven.” They are, like all of his work, classically accomplished works of art. But unlike Beardsley, Doré seems to miss the strain of absurdism and dark humor that runs through all of Poe’s work (or at least the way I’ve read him), though it’s true that “The Raven” relies on atmosphere and suggestion for its effect, rather than torture, murder, and plague. In the later, 1923 edition of Tales of Mystery and Imagination illustrated by Irish artist Harry Clarke, we find the best qualities of Beardsley and Doré combined: finely-detailed, fully-realized scenes, suffused with gothic sensuality, symbolism, grotesque weirdness, and an almost comically exaggerated sense of dread.

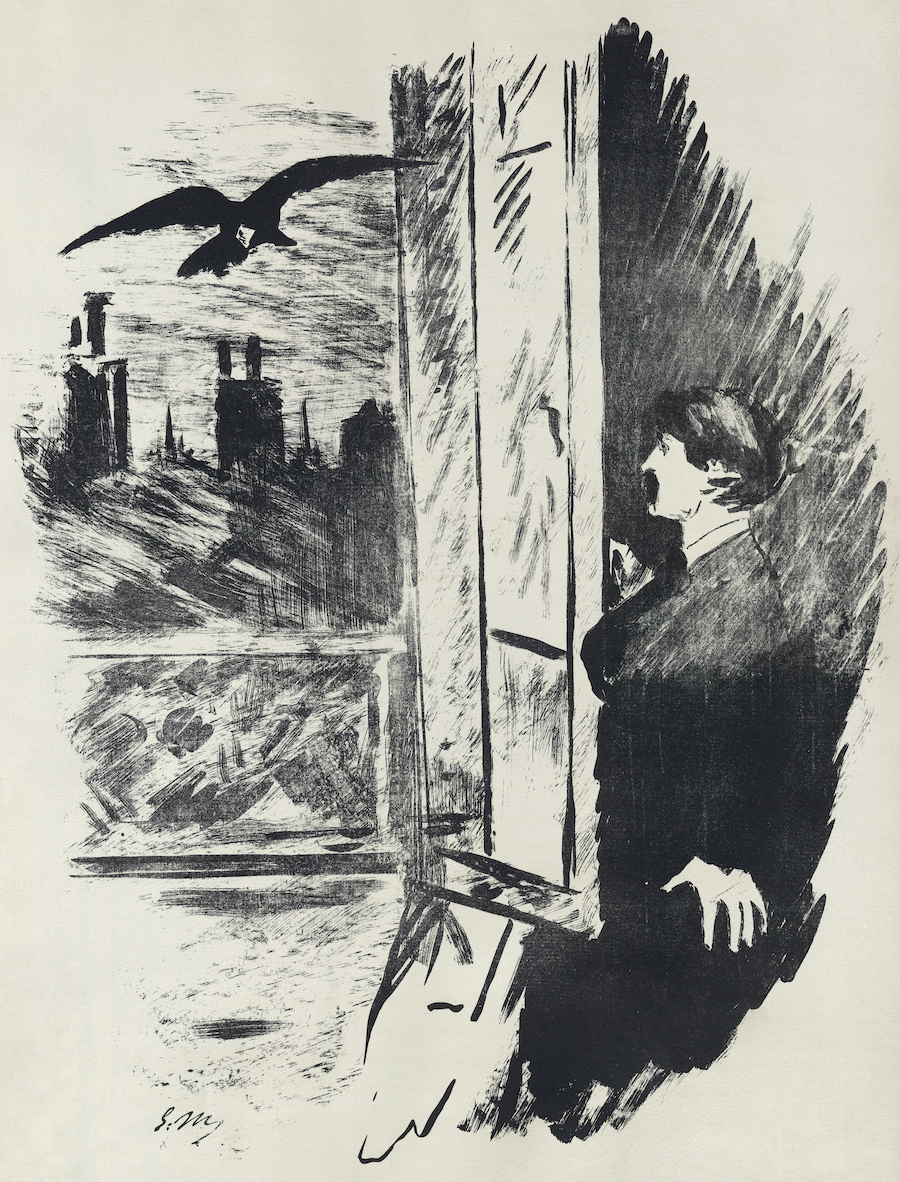

Poe significantly influenced the poetry of Charles Baudelaire and Stéphane Mallarmé, and Clarke foregrounds in his work many of the qualities those poets did—the tangling up of sex and death in images that attract and repulse at the same time. Early Impressionist master Édouard Manet also illustrated an 1875 edition of “The Raven,” translated into French by Mallarmé. Manet draws the French poet/translator as the speaker of the poem (recognizable by his pushbroom mustache).

Manet’s minimal drawings of the poem contrast starkly with Doré’s elaborate engravings. Just as readers might imagine Poe’s macabre stories in innumerable ways, so too the artists who have illustrated his work. See contemporary illustrations for “The Tell-Tale Heart,” for example, by South African artist Pencilheart Art and Brooklyn-based illustrator Daniel Horowitz, and recommend your favorite Poe artist in the comments below.

Related Content:

Harry Clarke’s Hallucinatory Illustrations for Edgar Allan Poe’s Stories (1923)

Aubrey Beardsley’s Macabre Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s Short Stories (1894)

Gustave Doré’s Splendid Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Raven” (1884)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness