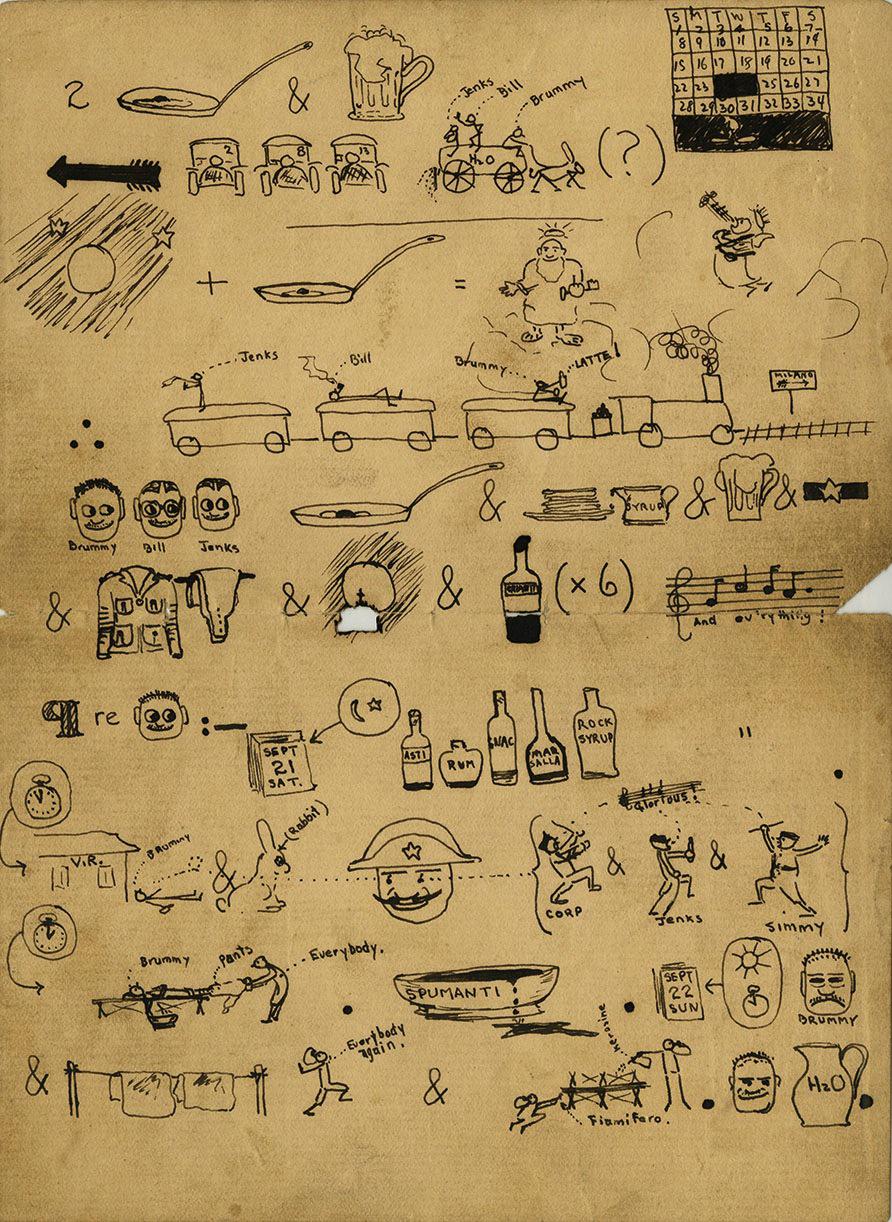

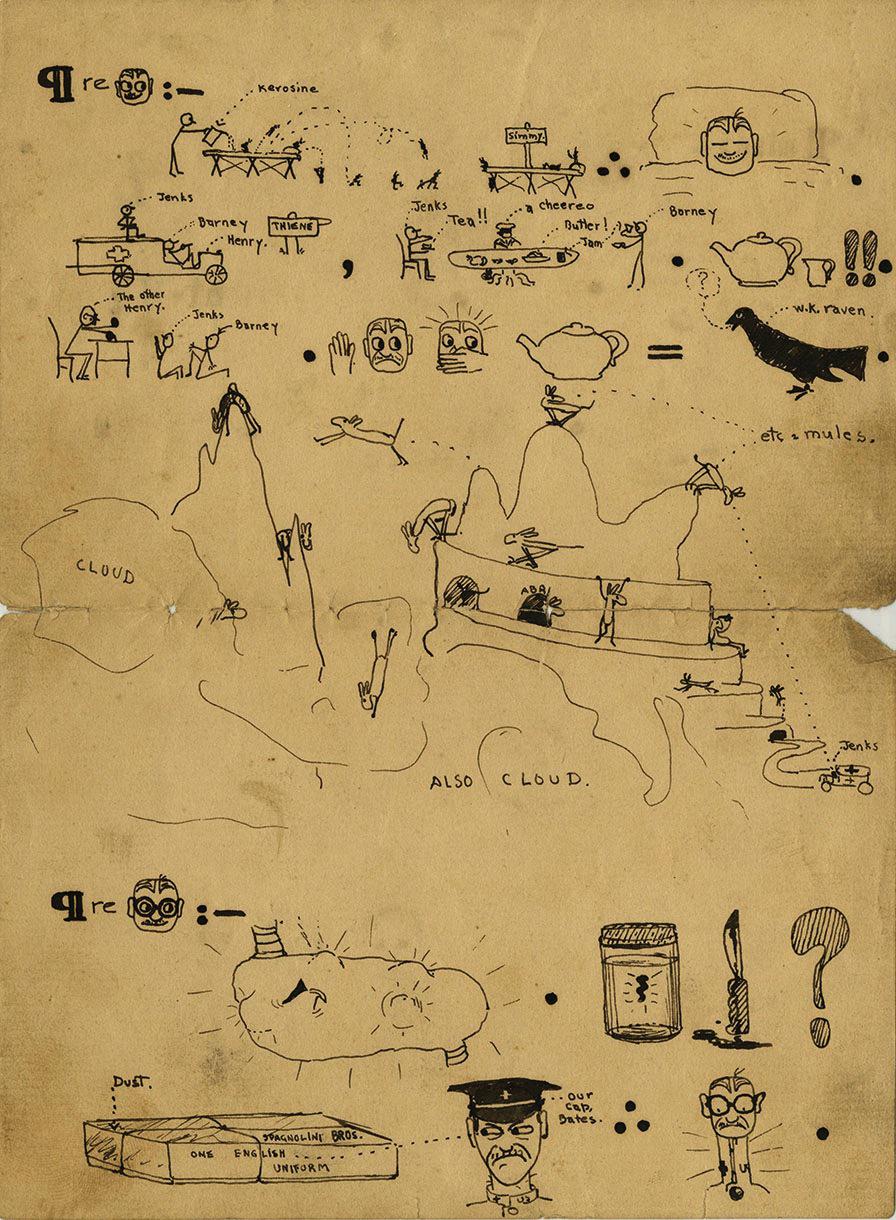

Most of us enter Jack Kerouac’s world through his 1959 novel On the Road. Those of us who explore it more deeply thereafter may find much more than we expected to: Kerouac’s inner life came out not just in his formidable body of written work, but in spoken-word jazz albums, fantasy baseball materials, and even paintings. Though Kerouac has now been gone for nearly half a century, it wasn’t until just last year that his works of visual art were brought together: Kerouac: Beat Painting did it in book form, and the Museo Maga near Milan put on an exhibition of the more than 80 pieces it could find, beginning with his first self-portrait, drawn at the age of nine.

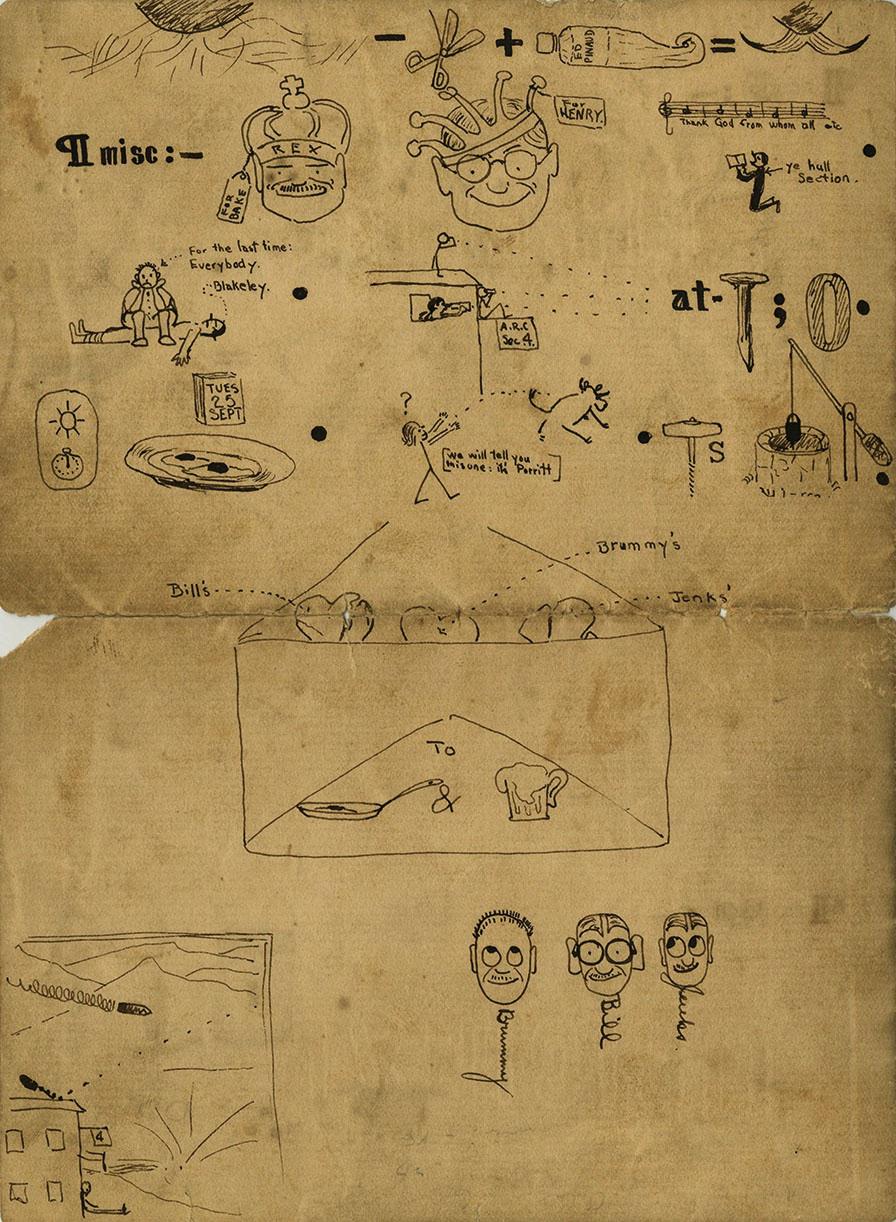

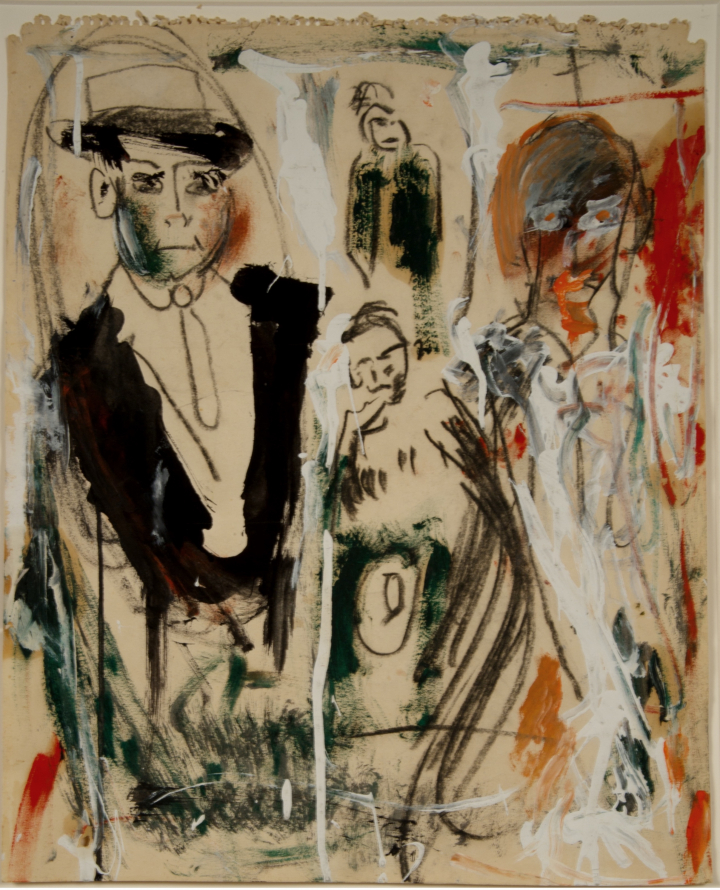

Kerouac had an interest in portraiture in general: the book, the Independent’s David Barnett writes, “begins with a series of portraits of people Kerouac knew or admired. They also highlight Kerouac’s complicated spirituality: brought up a Catholic, he later embraced Buddhism and developed an almost ‘holy fool’ persona.” Cardinal Giovanni Montini, later to become Pope Paul VI, counts as one particularly notable subject of a Kerouac portrait; another is Kerouac’s fellow culture-defining writer Truman Capote (above), who at the time Kerouac painted him had already criticized On the Road publicly, and harshly. Sandrina Bandera, a curator of the exhibition and editor of Kerouac: Beat Painting, ascribes to the Capote portrait “a dynamic, almost violent quality.”

The same could perhaps be said of all of Kerouac’s creative output, and certainly of much of his best-known writing. And like many a creator known for his visceral nature, Kerouac made strict rules and built systems to work within: his 1959 manifesto for painting includes the commandments “use only one brush” and “stop when you want to ‘improve’… it’s done.” Detractors of Kerouac’s work will certainly see a connection between his visual art and his verbal art in his self-directed commandment to “pile it on,” but who could call the “beat painting” of this Beat Generation figurehead not of an aesthetic and intellectual piece with everything else that Bandera describes, unimprovably, as “that potent entity known as Jack Kerouac.”

via Hyperallergic

Related Content:

Jack Kerouac’s Hand-Drawn Map of the Hitchhiking Trip Narrated in On the Road

Jack Kerouac Lists 9 Essentials for Writing Spontaneous Prose

Jack Kerouac Reads from On the Road (1959)

Jack Kerouac Was a Secret, Obsessive Fan of Fantasy Baseball

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.