Had the gloom-haunted Edward Gorey found a way to have a love child with Dorothy Parker, their issue might well have been Lemony Snicket, the pseudonymous author of a multivolume family chronicle brought out under the genteel appellation A Series of Unfortunate Events.

- Gregory Maguire, The New York Times

Author Daniel Handler—aka Lemony Snicket—was but a child when he fortuitously stumbled onto the curious oeuvre of Edward Gorey.

The little books were illustrated, hand-lettered, and mysterious. They alluded to terrible things befalling innocents in a way that made young Handler laugh and want more, though he shied from making such a request of his parents, lest the books constitute pornography.

(His fear strikes this writer as wholly reasonable—my father kept a copy of The Curious Sofa: A Pornographic Work by Ogdred Weary—aka Edward Gorey—stashed in the bathroom of my childhood home. Its perversions were many, though far from explicit and utterly befuddling to a third grade bookworm. The exceedingly economical text hinted at a multitude of unfamiliar taboos, and Gorey the illustrator understood the value of a well-placed ornamental urn.)

Interviewed above for Christopher Seufert’s upcoming feature-length Gorey documentary, Handler is effusive about the depth of this early influence:

The gothic setting. (Handler always fancied that an in-person meeting with Gorey would resemble the first 20 minutes of a Hammer horror movie.)

The dark, unwinking humor arising from a plot as grim as that of The Hapless Child, or The Blue Aspic, the first title young Handler purchased with his own money.

An intentionally murky pseudonym geared to ignite all manner of wildly readerly speculation as to the author’s lifestyle and/or true identity. (Gorey attributed various of his works to Dogear Wryde, Ms. Regera Dowdy, Eduard Blutig, O. Müde and the aforementioned Ogdred Weary, among others.)

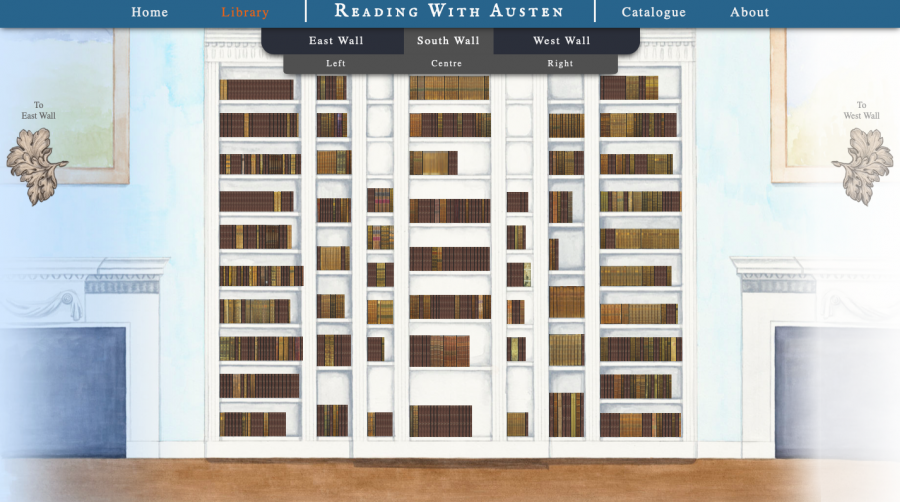

Even Lemony Snickett’s website carries a strong whiff of Gorey.

In acknowledgment of this debt, Handler sent copies of the first two Snickett books to the reclusive author, along with a fan letter that apologized for ripping him off. Gorey died in April 2000, a couple of weeks after the package was posted, leaving Handler doubtful that it was even opened.

Handler namechecks other artists who operate in Gorey’s thrall: filmmakers Tim Burton and Michel Gondry, musicians Amanda Palmer and Trent Reznor, and novelist Neil Gaiman.

Perhaps owing to the spectacular popularity of Snickett’s Series of Unfortunate Events, Gorey has lately become a bit more of an above-ground discovery for young readers. Scholastic has a free Edward Gorey lesson plan, geared to grades 6–12.

More information about Christopher Seufert’s Gorey documentary, with animations by Ben Wickey and the active participation of its subject during his final four years of life, can be found here.

Related Content:

Edward Gorey Talks About His Love Cats & More in the Animated Series, “Goreytelling”

Edward Gorey Illustrates H.G. Wells’ The War of the Worlds in His Inimitable Gothic Style (1960)

The First American Picture Book, Wanda Gág’s Millions of Cats (1928)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 9 for another season of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.