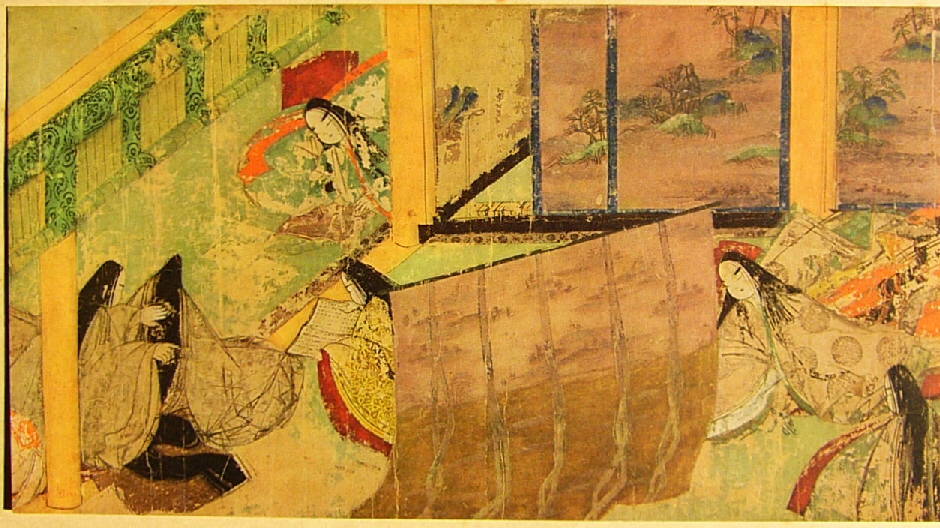

In 1936 — perhaps the darkest year of his life — F. Scott Fitzgerald was convalescing in a hotel in Asheville, North Carolina, when he offered his nurse a list of 22 books he thought were essential reading. The list, above, is written in the nurse’s hand.

Fitzgerald had moved into Asheville’s Grove Park Inn that April after transferring his wife Zelda, a psychiatric patient, to nearby Highland Hospital. It was the same month that Esquire published his essay “The Crack Up”, in which he confessed to a growing awareness that “my life had been a drawing on resources that I did not possess, that I had been mortgaging myself physically and spiritually up to the hilt.”

Fitzgerald’s financial and drinking problems had reached a critical stage. That summer he fractured his shoulder while diving into the hotel swimming pool, and sometime later, according to Michael Cody at the University of South Carolina’s Fitzgerald Web site, “he fired a revolver in a suicide threat, after which the hotel refused to let him stay without a nurse. He was attended thereafter by Dorothy Richardson, whose chief duties were to provide him company and try to keep him from drinking too much. In typical Fitzgerald fashion, he developed a friendship with Miss Richardson and attempted to educate her by providing her with a reading list.”

It’s a curious list. Shakespeare is omitted. So is James Joyce. But Norman Douglas and Arnold Bennett make the cut. Fitzgerald appears to have restricted his selections to books that were available at that time in Modern Library editions. At the top of the page, Richardson writes “These are books that Scott thought should be required reading.”

- Sister Carrie, by Theodore Dreiser

- The Life of Jesus, by Ernest Renan

- A Doll’s House, by Henrik Ibsen

- Winesburg, Ohio, by Sherwood Anderson

- The Old Wives’ Tale, by Arnold Bennett

- The Maltese Falcon, by Dashiel Hammett

- The Red and the Black, by Stendhal

- The Short Stories of Guy De Maupassant, translated by Michael Monahan

- An Outline of Abnormal Psychology, edited by Gardner Murphy

- The Stories of Anton Chekhov, edited by Robert N. Linscott

- The Best American Humorous Short Stories, edited by Alexander Jessup

- Victory, by Joseph Conrad

- The Revolt of the Angels, by Anatole France

- The Plays of Oscar Wilde

- Sanctuary, by William Faulkner

- Within a Budding Grove, by Marcel Proust

- The Guermantes Way, by Marcel Proust

- Swann’s Way, by Marcel Proust

- South Wind, by Norman Douglas

- The Garden Party, by Katherine Mansfield

- War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy

- John Keats and Percy Bysshe Shelley: Complete Poetical Works

via The University of South Carolina

Related Content:

Ernest Hemingway Creates a Reading List for a Young Writer, 1934

Seven Tips From F. Scott Fitzgerald on How to Write Fiction

Rare Footage of Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald From the 1920s