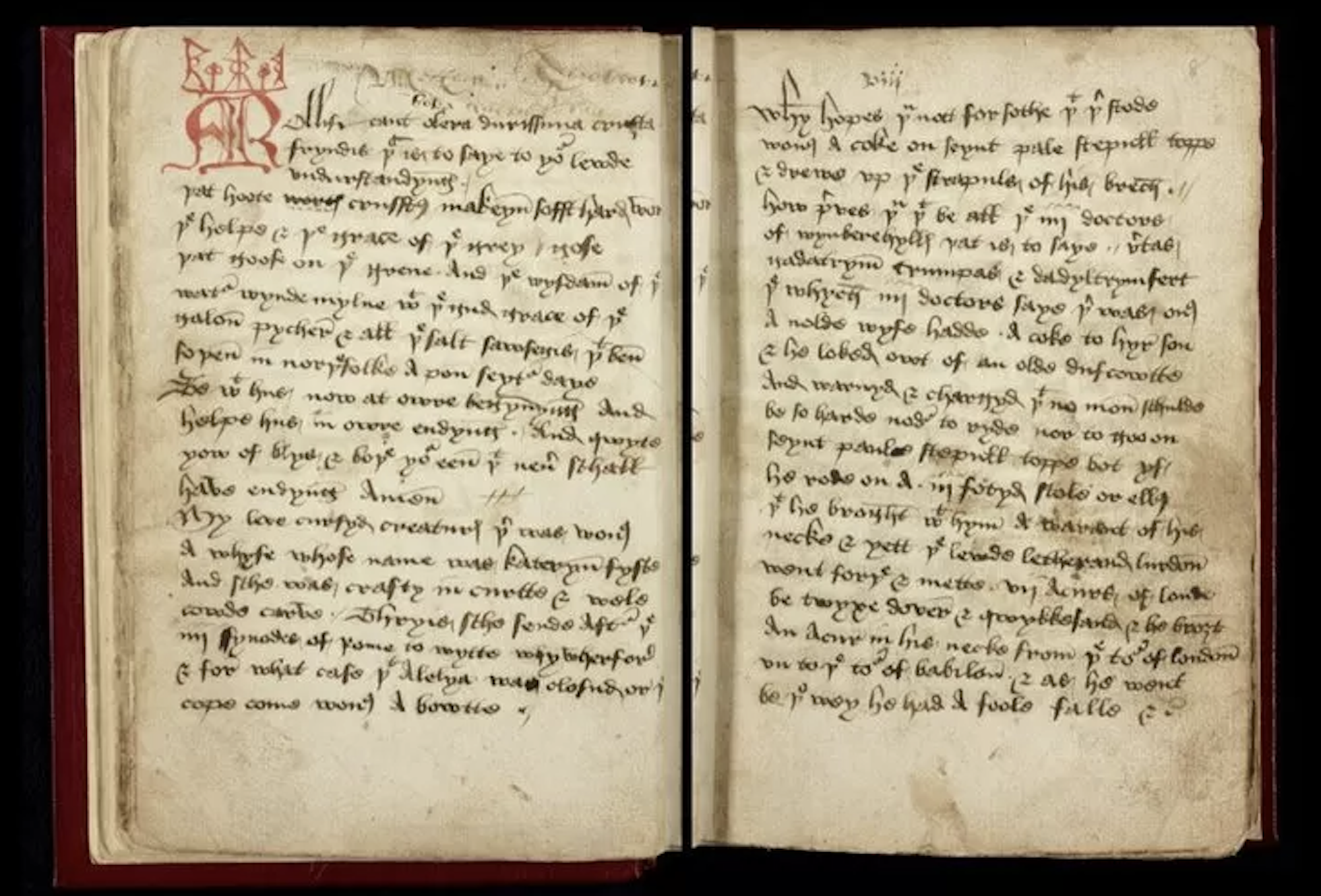

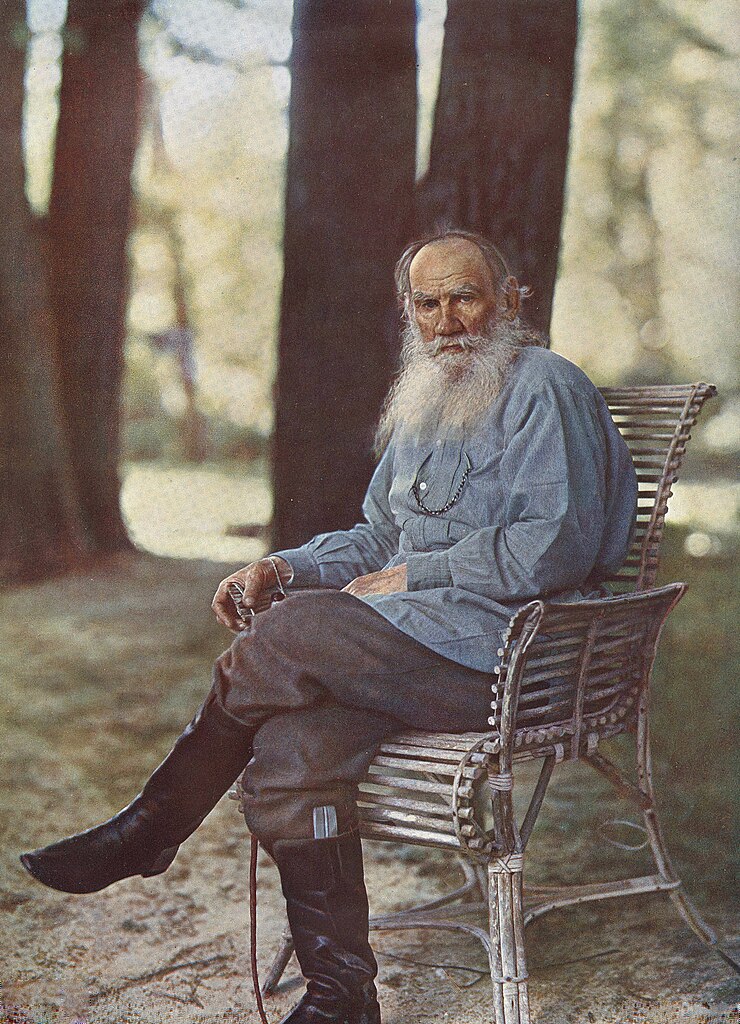

The photo above depicts Lev Nikolayevich Tolstoy, better known in the English-speaking world as Leo Tolstoy. It dates from 1908, when he had nearly all his work behind him: the major novels War and Peace and Anna Karenina, of course, but also the acclaimed late book The Death of Ivan Ilyich. His own death, in fact, lay not much more than two years before him. (See footage of the final days of his life here.) This didn’t offer much of a window of opportunity to the chemist Sergey Prokudin-Gorsky, who had recently developed a photography process that could capture the great man of letters in “true color” — and who understood that such a portrait would score a promotional coup for his innovation.

“After many years of work, I have now achieved excellent results in producing accurate colors,” Prokudin-Gorsky wrote to Tolstoy early that same year. “My colored projections are known in both Europe and in Russia. Now that my method of photography requires no more than 1 to 3 seconds, I will allow myself to ask your permission to visit for one or two days (keeping in mind the state of your health and weather) in order to take several color photographs of you and your spouse.” After receiving that permission, Prokudin-Gorsky spent two days at Yasnaya Polyana, Tolstoy’s family estate, where he took color pictures of not just the man himself but his working quarters and the surrounding grounds.

“A few months later, in its August 1908 issue, The Proceedings of the Russian Technical Society ran the following announcement describing ‘the first Russian color photoportrait,’ a color photograph of L. N. Tolstoy,” according to Tolstoy Studies Journal. The resulting fame drew Prokudin-Gorsky an invitation to show his work to Tsar Nicholas II, who subsequently furnished him with the resources to spend ten years photographically documenting Russia in color. “To this day, nobody knows exactly what camera Prokudin-Gorsky used,” writes Kai Bernau at Words that Work, “but it was likely a large wooden camera with a special holder for a sliding glass negative plate, taking three sequential monochrome photographs, each through a different colored filter.” This appears to be a technological descendant of the process developed in the early eighteen-sixties by Scottish physicist-poet James Clerk Maxwell, creator of the first color photograph in history.

To view that photograph, Maxwell “projected the three slides using three different projectors, each affixed with the same color filter that had been used to produce the slide.” Prokudin-Gorsky, too, had to project his photos, though he did later make color prints; “he also published it, in significant numbers, as a collectible postcard,” says Tolstoy Studies Journal, adding that the version seen here is a scan of one such postcard. “How accurately a lithographed reproduction like the one above of Tolstoy represents the ‘real’ colors of Prokudin-Gorsky’s original projected image is debatable”; the basic technological difference between “subtractive” lithography and “additive’ projection means that we can’t be seeing quite the same picture of Tolstoy that the Tsar did — but then, it’s a good a likeness of him as we’re ever going to get.

Related content:

The Very Last Days of Leo Tolstoy Captured on Video

Tsarist Russia Comes to Life in Vivid Color Photographs Taken Circa 1905–1915

Colorized Photos Bring Walt Whitman, Charlie Chaplin, Helen Keller & Mark Twain Back to Life

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.