51 years ago, Hunter S. Thompson wrote Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail ’72, which “is still considered a kind of bible of political reporting,” noted Matt Taibbi in a 40th anniversary edition of the book. Fear and Loathing ’72 entered the canon of American political writing for many reasons. But if you’re looking for one bottom-line explanation, it probably comes down to this: Says Taibbi, “Thompson stared right into the flaming-hot sun of shameless lies and cynical horseshit that is our politics, and he described exactly what he saw—probably at serious cost to his own mental health, but the benefit to us was [his legendary book].”

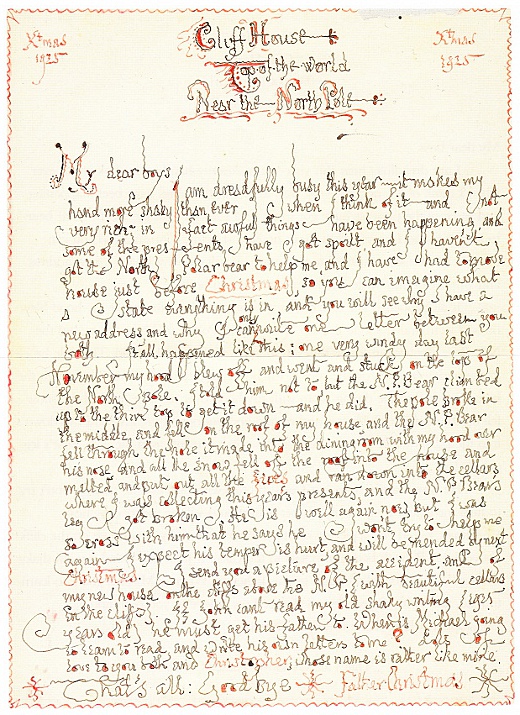

Thompson may have reached some journalistic apogee with his coverage of the ’72 Nixon-McGovern campaign. But his political writing hardly stopped there. The Gonzo journalist covered the ’76 election for Rolling Stone magazine. And inevitably he crossed paths with Jimmy Carter (RIP), the eventual winner of the election. Above, Thompson recalls the day when Carter first made an impression upon him.

It happened at the University of Georgia School of Law on May 4, 1974. Speaking before a gathering of alumni lawyers, Carter upset their celebratory occasion when he dismantled the criminal justice system they were so proud of. And Carter particularly caught Thompson’s attention when he traced his sense of social justice back to a song written by Bob Dylan:

The other source of my understanding about what’s right and wrong in this society is from a friend of mine, a poet named Bob Dylan. After listening to his records about “The Ballad of Hattie Carol” and “Like a Rolling Stone” and “The Times, They Are a‑Changing,” I’ve learned to appreciate the dynamism of change in a modern society.

I grew up as a landowner’s son. But I don’t think I ever realized the proper interrelationship between the landowner and those who worked on a farm until I heard Dylan’s record, “I Ain’t Gonna Work on Maggie’s Farm No More.” So I come here speaking to you today about your subject with a base for my information founded on Reinhold Niebuhr and Bob Dylan.

You can read the full text of Carter’s speech here. It’s also worth watching a related clip below, where Thompson elaborates on Carter, his famous speech and his alleged mean streak that put him on the same plane as Muhammad Ali and Sonny Barger (the godfather of The Hells Angels).

Note: An earlier version of this post first appeared on our site in 2012. With the passing of President Carter, it seemed like a good time to bring it back.

Related Content

The 2,000+ Films Watched by Presidents Nixon, Carter & Reagan in the White House

Hunter Thompson Explains What Gonzo Journalism Is, and How He Writes It (1975)