Before her literary fame, her stormy relationship with Ted Hughes and her crippling battles with depression, Sylvia Plath was an enthusiastic student at Smith College. “The world is splitting open at my feet like a ripe, juicy watermelon,” she wrote to her mother. “If only I can work, work, work to justify all of my opportunities.”

During her junior year, she broke her leg on a skiing trip in upstate New York. The accident landed her briefly in the hospital and she wound up with a cast on her leg. Her mood darkened.

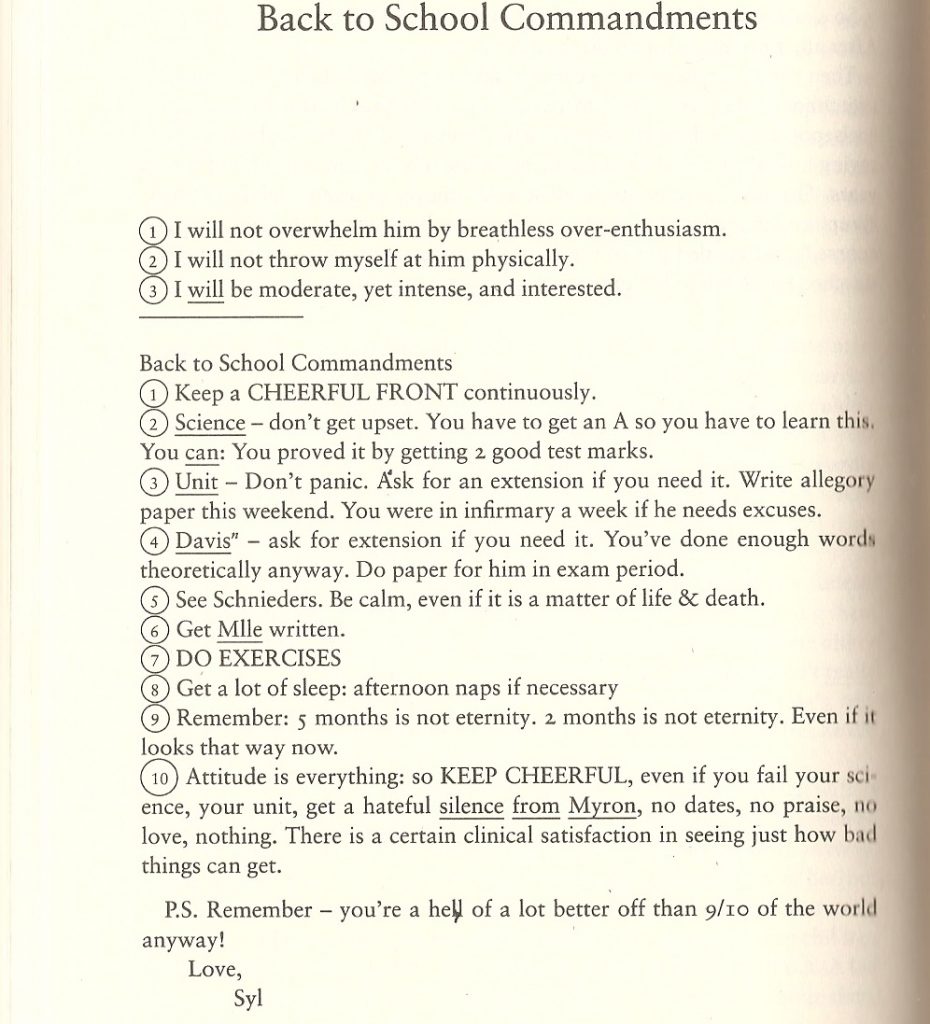

Psyching herself out for her return to college, she wrote in her diary a pair of lists.

The first list is a short series of rules about how to behave around her new beau, Myron Lotz. All three points are good advice for anyone who is utterly smitten, particularly number two – “I will not throw myself at him physically.” In the end, Plath’s relationship with Lotz didn’t amount to much. She reportedly commemorated him within her poem “Mad Girl’s Love Song” with the refrain “I think I made you up inside my head.”

The second list is a collection of “Back to School Commandments.” These commandments included asking her English prof Robert Gorham Davis for an extension; consulting with her German teacher Marie Schnieders (“Be calm,” she writes mysteriously, “even it is a matter of life & death.”); and completing her application to be a guest editor for Mademoiselle magazine. (She nailed that last task.)

The list’s final commandment comes off bleaker than the mildly panicky motivational tone of the rest of the list. “Attitude is everything: so KEEP CHEERFUL, even if you fail your science, your unit, get a hateful silence from Myron, no dates, no praise, no love, nothing. There is a certain clinical satisfaction in seeing just how bad things can get.”

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2015.

via The Excellent Lists of Note book

Related Content:

Why Should We Read Sylvia Plath? An Animated Video Makes the Case

Christopher Hitchens Creates a Revised List of The 10 Commandments for the 21st Century

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.