Knowing the transformative effect an inspired teacher can have on an “unreachable” student, one can only hope that geography and luck will conspire to bring the two together at an early point in the child’s development.

Helen Keller, author, activist, and poster girl for surmounting near-impossible odds, certainly lucked out in the teacher department. Rendered deaf and blind by a fever contracted at 19 months, Keller earned a reputation as a holy terror in a family ill-equipped to understand what her wild rages might signify.

Her well-connected parents consulted various experts, including soon-to-be-friend, inventor Alexander Graham Bell, a trail that ultimately led to the Perkins School for the Blind and the 20-year-old Annie Sullivan.

Within a few short months of her arrival at the Keller family home, Sullivan led the nearly-seven-year-old Keller to her famous breakthrough at the water pump.

In a more conventional arrangement, the student would eventually leave her teacher for further educational pursuits, but Keller depended on Sullivan to translate other teachers’ lectures and classroom interactions. Sullivan accompanied her to Perkins School for the Blind, the Wright-Humason School for the Deaf, the Cambridge School for Young Ladies, and finally Radcliffe College, where Keller earned her BA.

The unusual boundaries of their teacher-student bond meant Keller lived with Sullivan and her husband in their Forest Hills home, a move that hastened the marriage’s unofficial but permanent end, according to Sullivan’s biographer, Kim Nielsen. It likely thwarted Keller’s single attempt at romance, with her temporary secretary, writer Peter Fagan, too.

For better and worse, their lives were forever entwined, each made more extraordinary by the presence of the other.

Their appearance in the 1930 Vitaphone newsreel, above, highlights the mandatory physical closeness they shared, as they demonstrate the process by which Keller learned to speak. Having learned to communicate via letters Sullivan finger spelled into her palm, Keller placed her fingers against Sullivan’s lips, throat and nose, to feeling the vibrations made when these familiar letters were spoken aloud.

Sullivan died six years after the newsreel was filmed, at which point, Polly Thomson, originally engaged as the ladies’ housekeeper, took over, serving as Keller’s interpreter and traveling companion for the next twenty years.

Related Content:

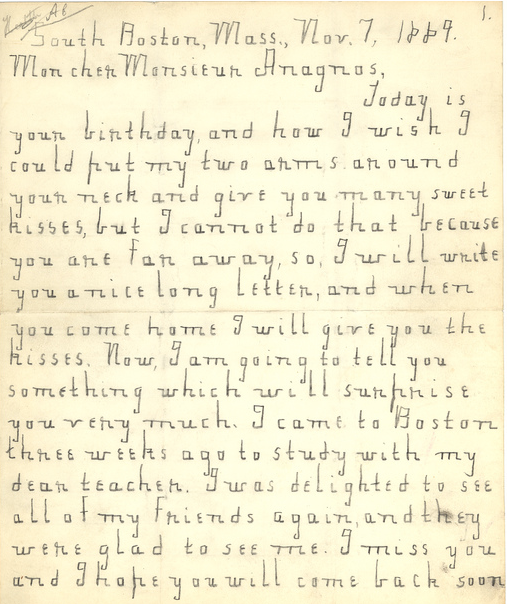

Helen Keller Had Impeccable Handwriting: See a Collection of Her Childhood Letters

Helen Keller Speaks About Her Greatest Regret — Never Mastering Speech

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Her play Zamboni Godot is opening in New York City in March 2017. Follow her @AyunHalliday.