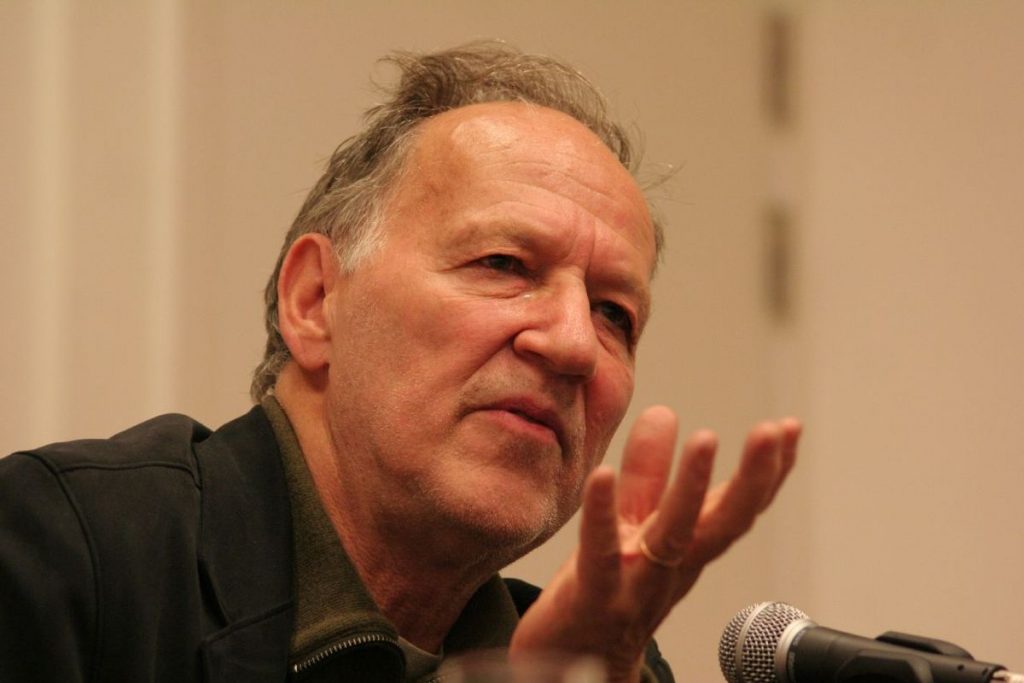

Image by Erinc Salor via Wikimedia Commons

There are few filmmakers alive today who have the mystique of Werner Herzog. His feature films and his documentaries are brilliant and messy, depicting both the ecstasies and the agonies of life in a chaotic and fundamentally hostile universe. And his movies seem very much to reflect his personality – uncompromising, enigmatic and quite possibly crazy. How else can you explain his willingness to risk life and limb to shoot in such forbidding places as the Amazonian rain forest or Antarctica?

In perhaps his greatest film, Fitzcarraldo — which is about a dreamer who hatches a scheme to drag a riverboat over a mountain — Herzog decides, for the purposes of realism, to actually drag a boat over a mountain. No special effects. No studios. In the middle of the Peruvian jungle.

The production, perhaps the most miserable in the history of film, is the subject of the documentary The Burden of Dreams. After six punishing months, a weary-looking Herzog described his surroundings:

I see it more full of obscenity. It’s just — Nature here is vile and base. I wouldn’t see anything erotical here. I would see fornication and asphyxiation and choking and fighting for survival and… growing and… just rotting away. Of course, there’s a lot of misery. But it is the same misery that is all around us. The trees here are in misery, and the birds are in misery. I don’t think they — they sing. They just screech in pain. […] But when I say this, I say this all full of admiration for the jungle. It is not that I hate it, I love it. I love it very much. But I love it against my better judgment.

His worldview brims with a heroic pessimism that is pulled straight out of the German Romantic poets. Nature is not some harmonious anthropomorphized playground. It is instead nothing but “chaos, hostility and murder.” For those sick of the cynical dishonesty of Hollywood’s current crop of Award-ready fare (hello, The Imitation Game), Herzog comes as a bracing tonic. An icon of what independent cinema should be rather than what it has largely become.

Below is Herzog’s list of advice for filmmakers, found on the back of his latest book Werner Herzog – A Guide for the Perplexed. (Hat tip goes to Jason Kottke for bringing it to our attention.) Some maxims are pretty specific to the world of moviemaking – “That roll of unexposed celluloid you have in your hand might be the last in existence, so do something impressive with it.” Other points are just plain good lessons for life — “Always take the initiative,” “Learn to live with your mistakes.” Read along and you can almost hear Herzog’s malevolent Teutonic lilt.

1. Always take the initiative.

2. There is nothing wrong with spending a night in jail if it means getting the shot you need.

3. Send out all your dogs and one might return with prey.

4. Never wallow in your troubles; despair must be kept private and brief.

5. Learn to live with your mistakes.

6. Expand your knowledge and understanding of music and literature, old and modern.

7. That roll of unexposed celluloid you have in your hand might be the last in existence, so do something impressive with it.

8. There is never an excuse not to finish a film.

9. Carry bolt cutters everywhere.

10. Thwart institutional cowardice.

11. Ask for forgiveness, not permission.

12. Take your fate into your own hands.

13. Learn to read the inner essence of a landscape.

14. Ignite the fire within and explore unknown territory.

15. Walk straight ahead, never detour.

16. Manoeuvre and mislead, but always deliver.

17. Don’t be fearful of rejection.

18. Develop your own voice.

19. Day one is the point of no return.

20. A badge of honor is to fail a film theory class.

21. Chance is the lifeblood of cinema.

22. Guerrilla tactics are best.

23. Take revenge if need be.

24. Get used to the bear behind you.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in January 2015.

Related Content:

Portrait Werner Herzog: The Director’s Autobiographical Short Film from 1986

Werner Herzog Picks His 5 Top Films

Werner Herzog and Cormac McCarthy Talk Science and Culture

Werner Herzog’s Eye-Opening New Film Reveals the Dangers of Texting While Driving

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring lots of pictures of badgers and even more pictures of vice presidents with octopuses on their heads. The Veeptopus store is here.