Image via the Wiltshire Museum

The burial rites of ancient and exotic peoples can seem outlandish to us, but there’s nothing particularly normal about the funeral traditions in the United States and the UK, where corpses are sent off to professional undertakers and made to look alive before they’re sealed in boxes and buried or turned into piles of ash.

Andrea DenHoed at The New Yorker refers to the practice of Tibetan Buddhist sky burials, in which “bodies are ritually dissected and left in the open to be consumed by vultures” and of the Torajans of Indonesia, who “have a ritual called Ma’Nene, in which bodies are disinterred, dressed in new clothes, and carried in a parade around the village.” These rites seem almost to mock our western fears of death.

Innovations on the funeral displace us further from the body. DenHoed writes, in 2016, of the then-relatively rare experience of attending a funeral over Skype, now commonplace by virtue of bleak necessity. It’s hard to say if high-tech mourning rituals like turning human remains into playable vinyl records brings us closer to accepting dead bodies, but they certainly bring us closer to an ancestral prehistoric past when at least some Bronze Age Britons turned the bones of their dead into musical instruments.

Is it any more macabre than turning relatives into diamonds? Who’s to say. The researchers who made this discovery, Dr. Thomas Booth and Joanna Brück, published their findings in the journal Antiquity under the tongue-in-cheek title “Death is not the end: radiocarbon and histo-taphonomic evidence for the curation and excarnation of human remains in Bronze Age Briton.”

What’s that now? Through radiocarbon-dating, the researchers, in other words, were able to determine that ancient people who lived between 2500–600 BC “were keeping and curating body parts, bones and cremated remains” of people they knew well, sometimes exhuming and ritually re-burying the remains in their homes, or just keeping them around for a couple generations.

“It’s indicative of a broader mindset where the line between the living and the dead was more blurred than it is today,” Booth tells The Guardian. “There wasn’t a mindset that human remains go in the ground and you forget about them. They were always present among the living.” This is hardly strange. The incredible amount of loss people will feel after COVID-19 will likely bring a proliferation of such rituals.

The find making headlines is a human thigh bone “that had been carved into a whistle” Josh Davis writes at the British Natural History Museum, and buried with another adult male. “When dated, it revealed that the thigh bone came from a person who probably lived around the same date as the man that it was buried with, meaning it is likely that it was someone that they knew in life, or were fairly close to.”

There doesn’t seem to be any suggestion that this was a common or widespread practice, but it’s not that dissimilar to wearing the remains of the dead as jewelry. “The Romans did it,” notes Glenn McDonald at National Geographic, “The Persians did it. The Maya did it.” And the Victorians, also, wore the remains of their dead, 4,000 years after their ancient ancestors. “The technologies change,” says McDonald, “but the basic human experience” of death, loss, and mourning remains the same.

The thigh bone whistle is on display at the Wiltshire Museum in the UK.

Related Content:

Hear the World’s Oldest Instrument, the “Neanderthal Flute,” Dating Back Over 43,000 Years

Hear a 9,000 Year Old Flute—the World’s Oldest Playable Instrument—Get Played Again

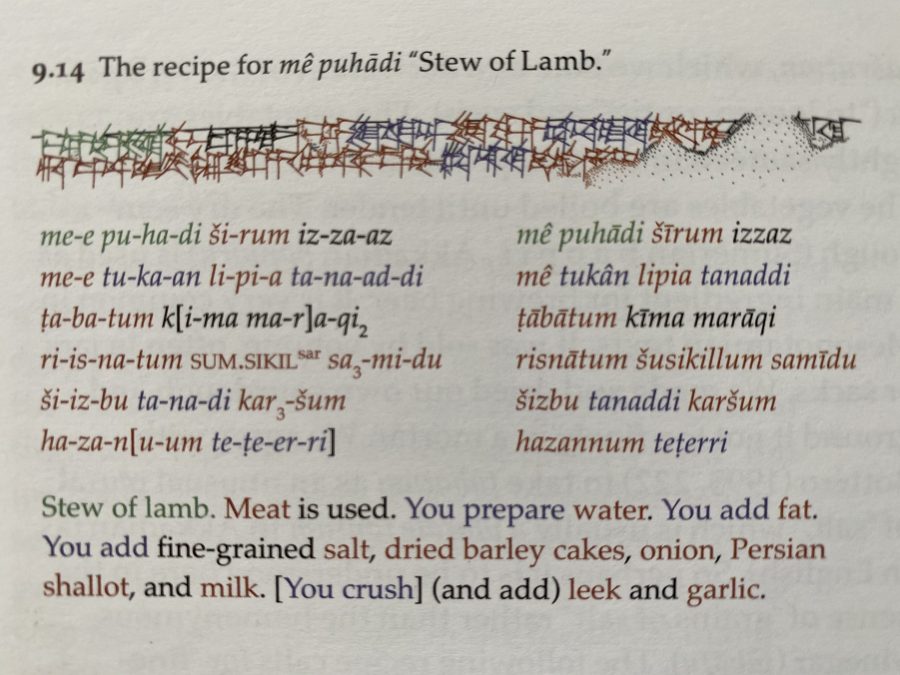

Listen to the Oldest Song in the World: A Sumerian Hymn Written 3,400 Years Ago

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness