In a time when people offer up every gesture as fodder for their adoring social media public, it’s a little difficult to imagine living a life as private as Jane Austen (1775–1817) did. And yet, the impression we have of her as shy and retiring is misleading. She did not achieve literary fame during her lifetime, it’s true, and it’s not clear that she desired it. As her nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh wrote in the Memoir of Jane Austen, the 1870 biographical sketch that helped popularize Austen in the 19th century, “her talents did not introduce her to the notice of other writers, or connect her with the literary world, or in any degree pierce through the obscurity of her domestic retirement.” Yet, reducing Austen’s personality, as Austen-Leigh does, to “the moral rectitude, the correct taste, and the warm affections with which she invested her ideal characters” misses her fierce intelligence and complexity.

Austen’s nephew’s portrait of her seems concerned with preserving those canons of propriety that she scrupulously documented and satirized in her novels. Perhaps this is partly why he characterizes her as a very shy person. But we know that Austen maintained a lively social life and kept up regular correspondence with family and friends. Her letter-writing, some of it excerpted in Austen-Leigh’s biography, gives us the distinct impression that she used her letters to practice the sharp portraits she drew in the novels of the mores and strictures of her social class. Thus it is surprising when her nephew tells us we are “not to expect too much from them.” “The style is always clear,” he opined, “and generally animated, while a vein of humour continually gleams through the whole; but the materials may be thought inferior to the execution, for they treat only of the details of domestic life. There is in them no notice of politics or public events; scarcely any discussions on literature, or other subjects of general interest.”

What Austen’s nephew seems not to understand is what her legions of adoring readers and critics have since come to see in her work: in Austen, the “details of domestic life” are revealed as microcosms of her society’s politics, public events, literature, and “subjects of general interest.” Austen-Leigh almost admits as much, despite himself, when he compares his aunt’s letters to “the nest some little bird builds of the materials nearest at hand, of the twigs and mosses supplied by the tree in which it is placed; curiously constructed out of the simplest matters.” In Austen’s hands, however, the small domestic dramas proceeding on the country estates around her were anything but simple matters. Letter-writing plays a central role in novels like Pride and Prejudice, as in most fiction of the period. The surviving Austen letters are worth reading as source material for the novels—or worth reading for their own sake, so enjoyable are their turns of phrase and withering characterizations.

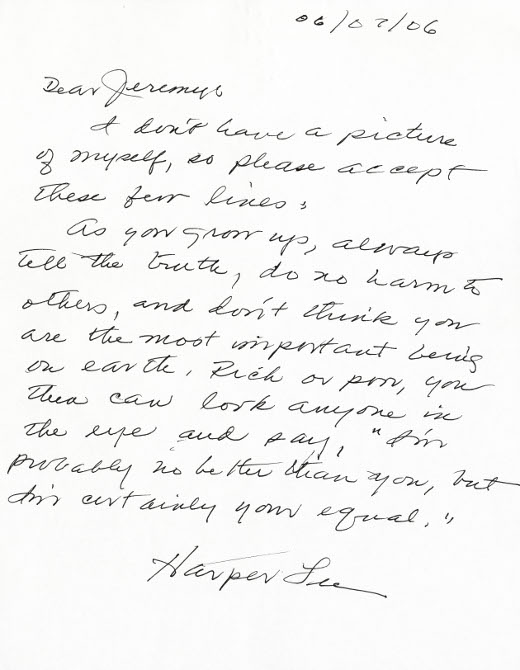

Take a November, 1800 letter Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra (preserved in the so-called “Brabourne edition” of her letters). Austen begins by confessing, “I believe I drank too much wine last night at Hurstbourne; I know not how else to account for the shaking of my hand to-day.” To the “venial error” of her hangover she attributes “any indistinctness of writing.” She then goes on to describe in vivid and very witty detail the ball she’d attended the night previous, taking the risk of boring her sister “because one is prone to think much more of such things the morning after they happen, than when time has entirely driven them out of one’s recollection.” Read an excerpt of her description below and see if the scene doesn’t come alive before your eyes:

There were very few beauties, and such as there were were not very handsome. Miss Iremonger did not look well, and Mrs. Blount was the only one much admired. She appeared exactly as she did in September, with the same broad face, diamond bandeau, white shoes, pink husband, and fat neck. The two Miss Coxes were there: I traced in one the remains of the vulgar, broad-featured girl who danced at Enham eight years ago; the other is refined into a nice, composed-looking girl, like Catherine Bigg. I looked at Sir Thomas Champneys and thought of poor Rosalie; I looked at his daughter, and thought her a queer animal with a white neck. Mrs. Warren, I was constrained to think, a very fine young woman, which I much regret. She has got rid of some part of her child, and danced away with great activity looking by no means very large. Her husband is ugly enough, uglier even than his cousin John; but he does not look so very old. The Miss Maitlands are both prettyish, very like Anne, with brown skins, large dark eyes, and a good deal of nose. The General has got the gout, and Mrs. Maitland the jaundice. Miss Debary, Susan, and Sally, all in black, but without any stature, made their appearance, and I was as civil to them as their bad breath would allow me.

You can read the letter in full at Letters of Note, who have included it in their excellent follow-up correspondence collection, More Letters of Note. For more context and other letters to Cassandra from this period, see this section of the Brabourne Austen letters.

via Letters of Note

Related Content:

Jane Austen Used Pins to Edit Her Abandoned Manuscript, The Watsons

Download the Major Works of Jane Austen as Free eBooks & Audio Books

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness