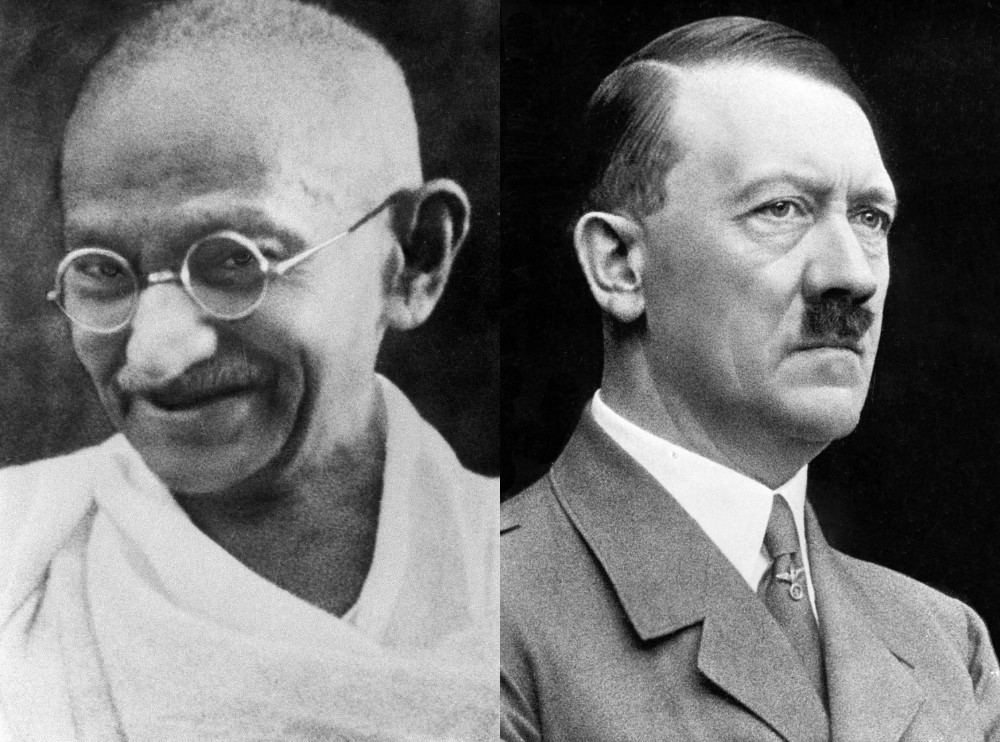

Image by George Leite, via Wikimedia Commons

At one time, writer Anaïs Nin’s reputation largely rested on her passionate, long-term love affair with novelist Henry Miller, whom she also financially supported while he wrote his best-known novels and became, writes Sady Doyle, a “darling of the avant-garde.” Nin herself was a marginalized, “unfashionable” writer, whose “frank portrayals of illegal abortions, extramarital affairs and incest” brought such critical opprobrium down on her that “by 1954, Nin believed the entire publishing industry saw her as a joke.” She had good reason to think so.

Miller’s notoriously censored books won him cult literary status, and inspired the Beats, Norman Mailer, Philip Roth, and many more hedonistic male writers seeking to turn their lives into art. Nin’s equally explicit work was met, she lamented, “with indifference, with insults.” Critics either ignored her novels, several of them self-published, or dismissed them as vulgar, artless, and worse. One headline, Doyle notes, called Nin “a monster of self-centeredness whose artistic pretentions now seem grotesque.”

All of that changed when Nin published the first volume of her diary in 1966. Thereafter, she achieved global fame as a feminist icon, and the next ten years saw the publication of an additional six volumes of her journals, then several more excerpts after her death in 1977. Most notably, Henry and June appeared in 1986 (subsequently made into a film by Philip Kaufman), a book which—in conjunction with the publication of her and Miller’s letters the following year—further added to the mythology of the two passionately erotic writers.

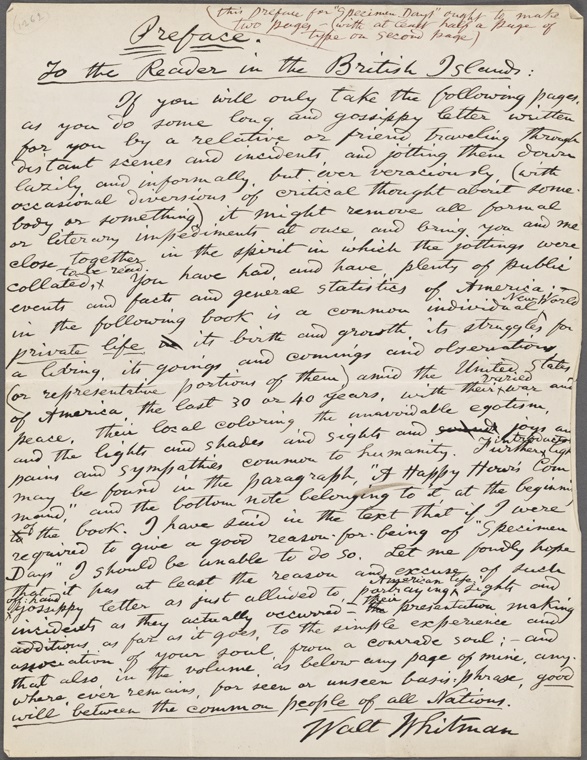

Nin had kept her diaries religiously since age 11, and has become known as “modernity’s most prolific and perceptive diarist,” writes Maria Popova, a distinction that has led to a tremendous resurgence in pop culture popularity in our time, when well-crafted self-revelation is de rigeur for artists, activists, online personalities, and aspirants of all kinds. Henry Miller is now “a marginalized and largely forgotten American writer” (or so claims his biographer Arthur Hoyle), and Nin has become a “patron saint of social media,” writes Doyle, a “proto-Lena-Dunham.” Pithy quotations from her diaries—properly credited or not—constantly circulate on Tumblr, Facebook, and Twitter.

A new generation just discovering Anaïs Nin can access her work in any number of ways—from hip, meme-heavy Tumblr accounts like Fuck Yeah Anais Nin to more formal online venues like the Anais Nin Blog, which aggregates biographies, podcasts, scholarship, bibliographies, controversies, and anything else one might want to know about the author. Anaïs Nin fans can also hear the author herself read from her famous diary in the audio here. At the top of the post, hear Nin’s reading, recorded in ’66, the year of the first volume’s publication. The complete recording runs about 60 minutes.

After the acclaim of Nin’s diaries, and the celebrity she enjoyed in her last decade, her reputation once again suffered, posthumously, as biographers and critics savaged her life and work in moralistic torrents of what would today be called “slut-shaming.” But Nin is now once again rightly revered as a writer fully dedicated to the art, no matter the reception or the audience. The astonishing stream of words that flowed from her, recording every detail of her experiences, “seems nothing less than phenomenal,” wrote Noel Young of Nin’s nonstop letter writing. When it came to the detailed, insightful, and acutely philosophical recording of her life, “the act of writing may have even surpassed the act of living.”

Related Content:

Simone de Beauvoir Explains “Why I’m a Feminist” in a Rare TV Interview (1975)

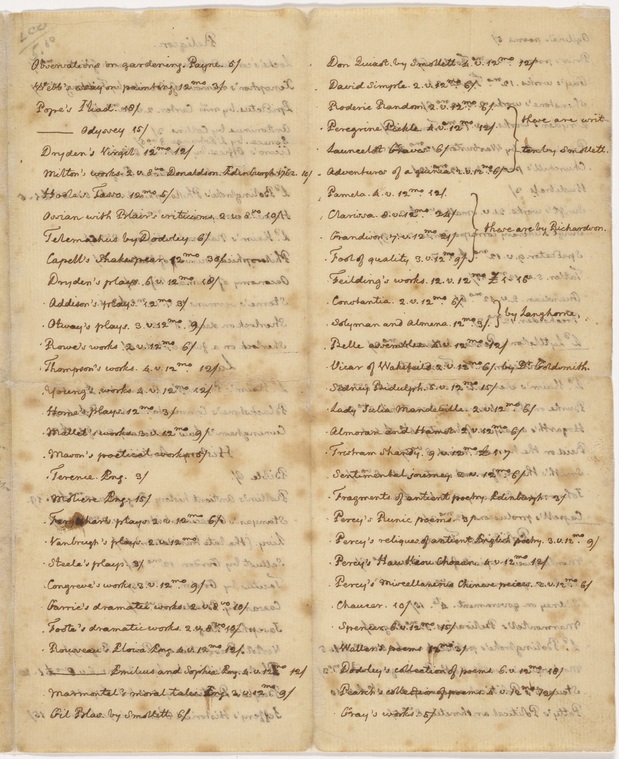

Henry Miller Makes a List of “The 100 Books That Influenced Me Most”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness