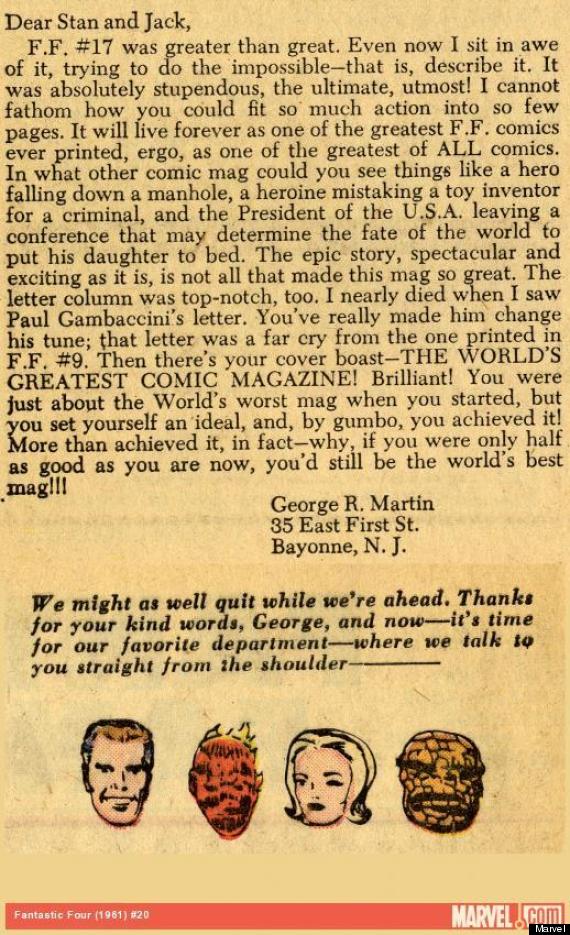

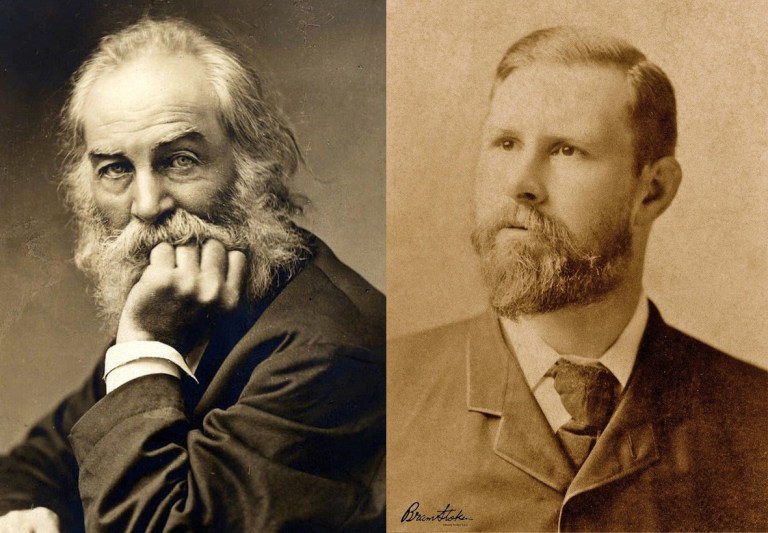

Every artist starts out as a fan, and in general we see the marks of early fandom on their mature work. The best, after all—as figures from Igor Stravinsky to William Faulkner have remarked—steal without compunction, taking what they like from their heroes and making it their own. But what exactly, we might wonder, did Dracula author Bram Stoker steal from his literary hero, Walt Whitman? I leave it to you to read the 1897 Gothic novel that spawned innumerable undead franchises and fandoms next to Whitman’s Leaves of Grass, the book that most inspired Stoker when it made its British debut in 1868.

First published in 1855, then rewritten over the rest of Whitman’s life, the book of poetry boldly celebrated the same pleasure and sensuality that Stoker’s novel made so dangerous. But Dracula was the work of a 50-year old writer. When Stoker first read Whitman, he was only 22, wide-eyed and romantic, and “grown from a sickly boy into a brawny athlete,” writes Meredith Hindley at the National Endowment for the Humanities magazine.

Whitman—himself a champion of robust masculine health (he once penned a manual called “Manly Health & Training”)—so appealed to the young Irish writer’s deep sensibilities that he wrote the older poet a gushing letter two years later in 1870.

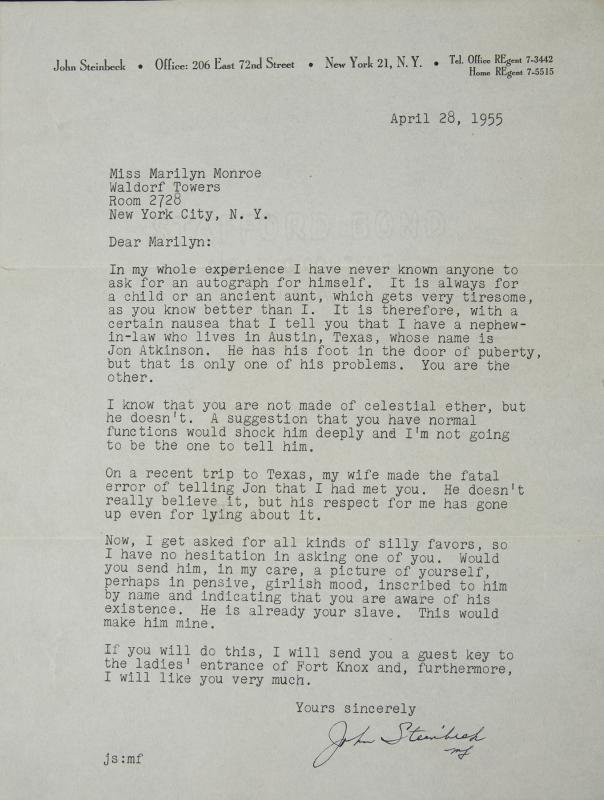

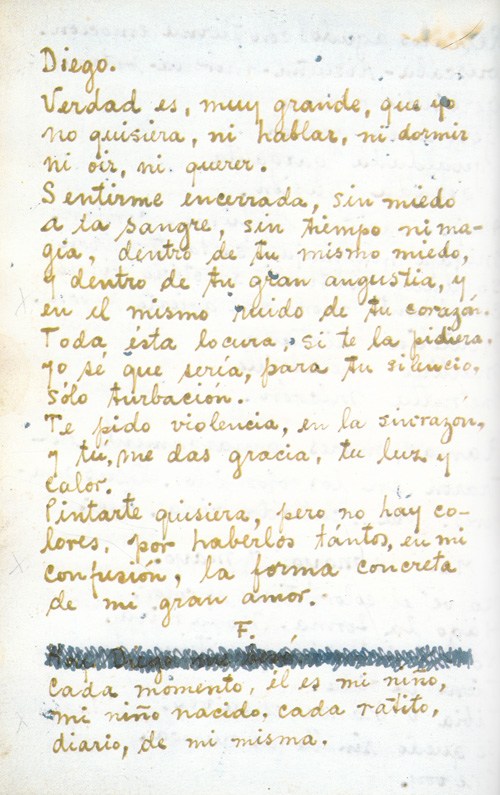

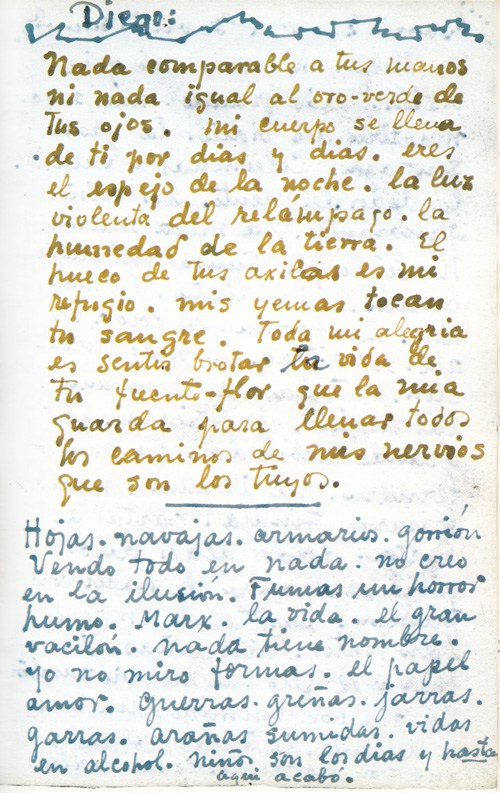

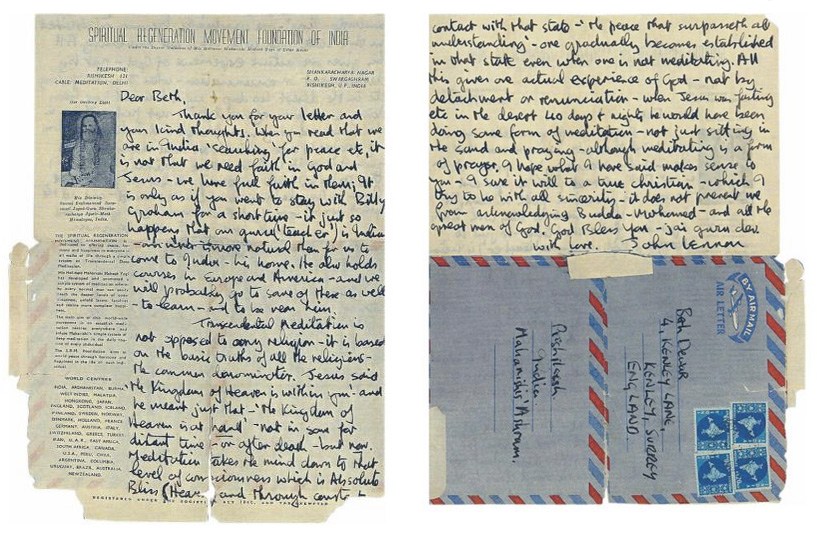

Stoker’s fan letter certainly shows the Whitmanian influence, “a long stream of sentiment cascading through various emotions,” as Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova describes it, including “surging confidence bordering on hubris, delicate self-doubt, absolute artist-to-artist adoration.” Whitman, flattered and charmed, wrote a reply, but only after four years, during which Stoker sat on his letter, ashamed to mail it. “For four years, it haunted his desk, part muse and part goblin.” When he finally gathered the courage in 1876 to rewrite the emotional letter and put it in the mail, he was rewarded with the kind of praise that must have absolutely thrilled him.

“You did so well to write to me,” Whitman replied, “so unconventionally, so fresh, so manly, and affectionately too.” Thus began a literary friendship that lasted until Whitman’s death in 1892 and seems to have been as welcome to Whitman as to his biggest fan. A stroke had nearly incapacitated the poet in 1873 and sapped his health and strength for the last two decades of his life, leaving him, as he wrote, with a physique “entirely shatter’d—doubtless permanently—from paralysis and other ailments.” But “I am up and dress’d,” he added, “and get out every day a little, live here quite lonesome, but hearty, and good spirits.”

One also wonders if Stoker would have received such a warm response if he had mailed his original letter unchanged. The “previously unsent effusion,” notes Popova, “opens with an abrupt directness unguarded even by a form of address.” Put another way, it’s blunt, melodramatic, and overly familiar to the point of rudeness: “If you are the man I take you to be,” he begins, “you will like to get this letter. If you are not I don’t care whether you like it or not and only ask that you put it in to the fire without reading any farther.” Contrast this with the revised communication, which begins with the respectful salutation, “My dear Mr. Whitman,” and continues in relatively formal, though still highly spirited, vein.

Stoker had mellowed and matured, but he never left behind his adoration for Whitman and Leaves of Grass. When he eloquently sums up the effect reading the book and its original 1855 preface had on him—he echoes the feelings of millions of fans throughout the ages who have found a voice that speaks to them from far away of feelings they know intimately but cannot express at home:

Be assured of this Walt Whitman—that a man of less than half your own age, reared a conservative in a conservative country, and who has always heard your name cried down by the great mass of people who mention it, here felt his heat leap towards you across the Atlantic and his soul swelling at the words or rather the thoughts.

Read Stoker’s original and revised letters and Whitman’s brief, touching response at Brain Pickings.

Related Content:

Mark Twain Writes a Rapturous Letter to Walt Whitman on the Poet’s 70th Birthday (1889)

Horror Legend Christopher Lee Reads Bram Stoker’s Dracula

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness