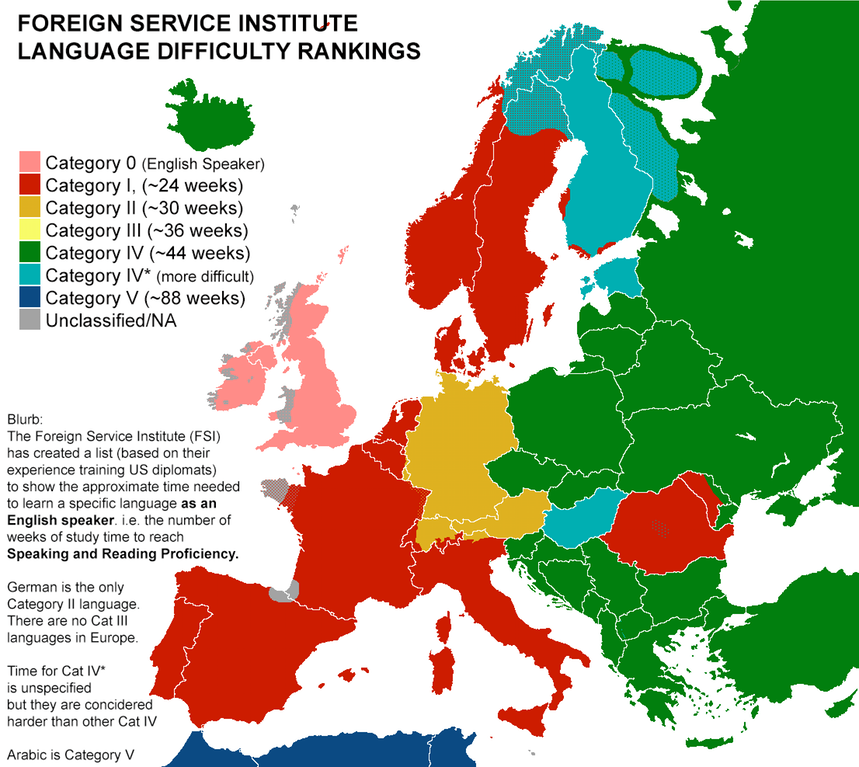

Earlier this week we featured the Foreign Service Institute’s list of languages ranked by how long they take to learn. Now that you have a sense of the relative life investment required to learn the tongue or tongues of your choice, how about a few words of advice on how to start? Or perhaps we’d do better, before the how, to consider the why. “A lot of us start with the wrong motivation to learn a language,” says Benny Lewis in his TED Talk “Hacking Language Learning.” Those motivations include “just to pass an exam, to improve our career prospects, or in my case for superficial reasons, to impress people.”

Real language learning, on the other hand, comes from passion for a language, for “the literature and the movies and being able to read in the language, and of course, to use it with people.” But Lewis, who now brands himself as “The Irish Polyglot,” says he got a late start on language-learning, convinced up until his early twenties that he simply couldn’t do it.

He cites five flimsy defenses he once used, and so many others still do, for their monolingualism: lack of a “language gene or talent,” being “too old to learn a second language,” not having the resources to “travel to the country right now,” and not wanting to “frustrate native speakers” by using the language before attaining fluency.

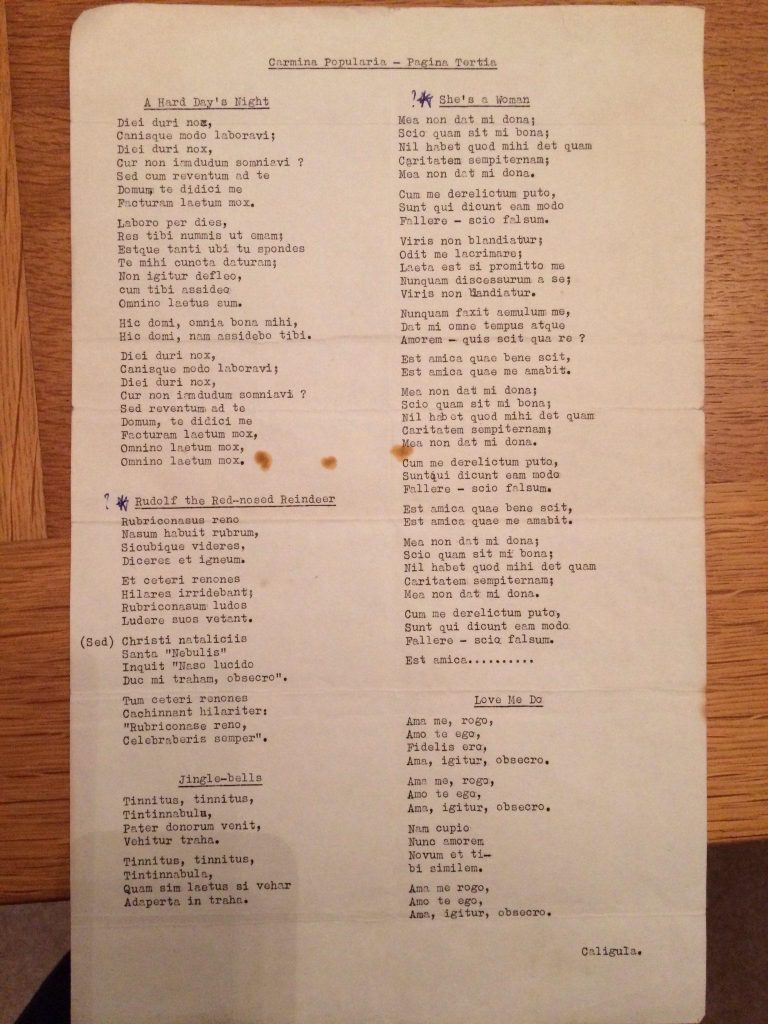

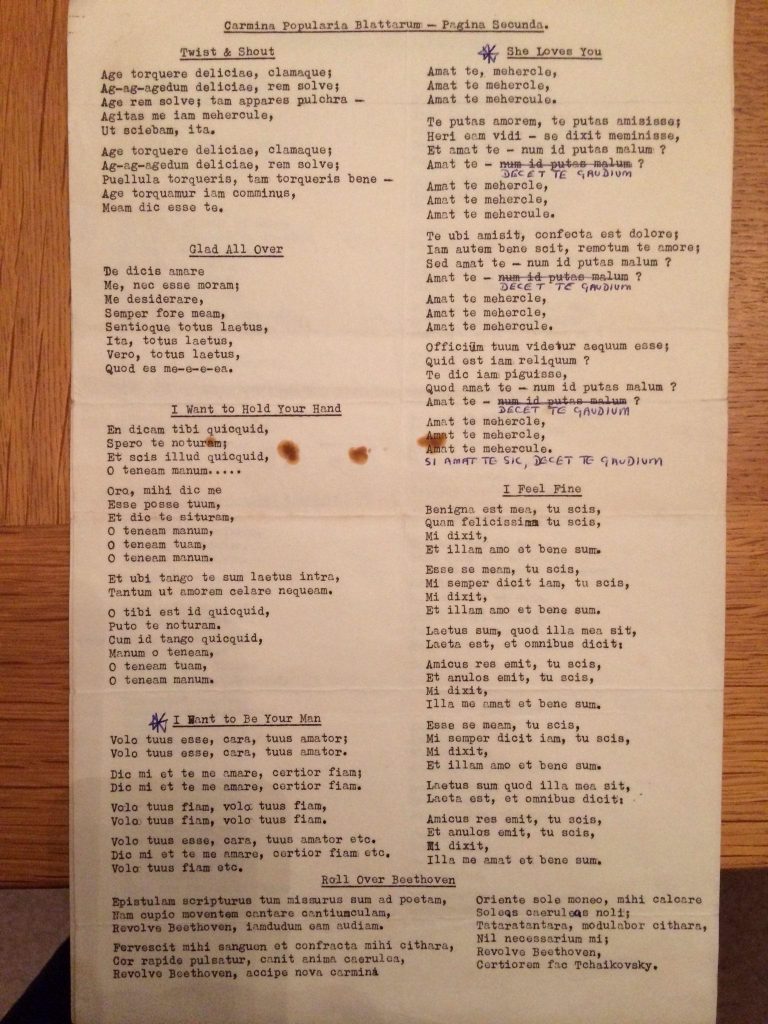

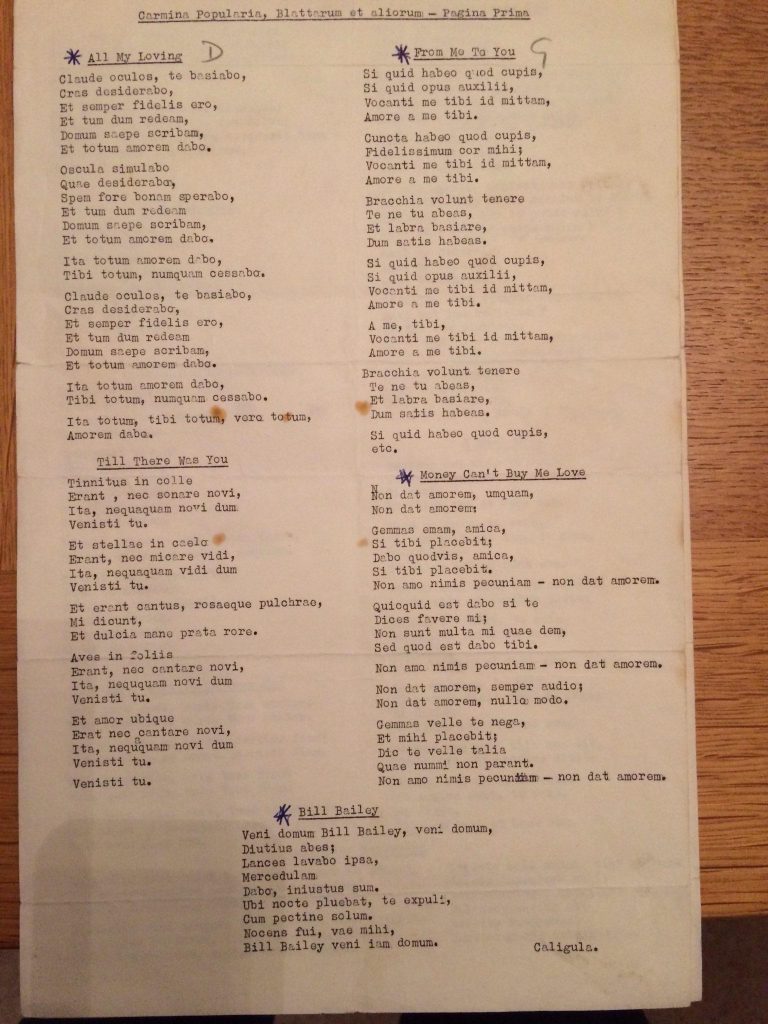

None of these, however, seem to have occurred to Tim Doner, who went viral at sixteen years with a video wherein he spoke twenty languages that he taught himself. He discusses that experience, and the fascinations and techniques that got him to that point and now well past it, in his talk “Breaking the Language Barrier.” At first put off by the drudgery of French classes in school, he only began to grasp the nature of language itself, as a kind of system breakable into masterable rules, when he began studying Latin.

Wanting to understand more about the conflict between Israel and Palestine, Doner decided to find his way into the subject through Hebrew, and specifically through rap music recorded in it. Using language study as a means of dealing with his insomnia, he discovered techniques to expand into other linguistic realms, such as the method of loci (i.e., remembering words by associating them with places), learning vocabulary in batches of similar sounds rather than similar meanings, and seeking out the foreign-language learners and speakers all around him — a relatively easy task for a New Yorker like Doner, but applicable nearly everywhere.

In “How to Learn Any Language in Six Months,” Chris Lonsdale delivers, and with a passion bordering on fury, a set of useful principles like “Focus on language content that is relevant to you,” “Use your new language as a tool to communicate from day one,” “When you first understand the message, you will unconsciously acquire the language.” This resonates with the advice offered by the much more laid-back Sid Efromovich in “Five Techniques to Speak any Language,” including an encouragement to “get things wrong and make mistakes,” a suggestion to “find a stickler” to help you identify and correct those mistakes, and a strategy for overcoming the pronunciation-hindering limitations of the “database” of sounds long established in your brain by your native language.

Your native language, in fact, will play the role of your most aggressive and persistent enemy in the struggle to learn a foreign one — especially if your native language is as widely used, to one degree or another, as English. And so Scott Young and Vat Jaiswal, in their talk “One Simple Method to Learn Any Language,” propose an absolute “no-English rule.” You can get results using it with a conversation partner in your homeland, while traveling for the purpose of language-learning, and especially if you’ve relocated to another country permanently.

With the rule in place, you’ll avoid the sorry fate of one fellow Young and Jaiswal know, “an American businessman who went to Korea, married a Korean women, had children in Korea, lived in Korea for twenty years, and still couldn’t have a decent conversation in Korean.” As an American living in Korea myself, I had to laugh at that: I could name at least three dozen long-term Western expatriates I’ve met in that very same situation. In my case, I spent a few years developing self-study habits for Korean and a couple other languages while still in America, and so didn’t have to implement them on the fly after moving here.

Even so, I still must constantly refine my language-learning strategy, incorporating routines like those laid out by English polyglot Matthew Youlden in “How to Speak any Language Easily”: seeking out exploitable similarities between the languages I know and the ones I want to know better, say, or finding sources of constant “passive” linguistic input. Personally, I like to listen to podcasts not just in foreign languages, but that teach one foreign language through another. And just as English-learners get good listening practice out of TED Talks like these, I seek them out in other languages: Korean, Japanese, Spanish, or wherever good old linguistic passion leads me next.

Related Content:

A Map Showing How Much Time It Takes to Learn Foreign Languages: From Easiest to Hardest

Learn 48 Languages Online for Free: Spanish, Chinese, English & More

The Tree of Languages Illustrated in a Big, Beautiful Infographic

Where Did the English Language Come From?: An Animated Introduction

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.