Contrary to somewhat popular belief, Chinese characters aren’t just little pictures. In fact, most of them aren’t pictures at all. The very oldest, whose evolution can be traced back to the “oracle bone” script of thirteenth century BC etched directly onto the remains of turtles and oxen, do bear traces of their pictograph ancestors. But most Chinese characters, or hanzi, are logographic, which means that each one represents a different morpheme, or distinct unit of language: a word, or a single part of a word that has no independent meaning. Nobody knows for sure how many hanzi exist, but nearly 100,000 have been documented so far.

Not that you need to learn all of them to attain literacy: for that, a mere 3,000 to 5,000 will do. While it’s technically possible to memorize that many characters by rote, you’d do better to begin by familiarizing yourself with their basic nature and structure — and in so doing, you’ll naturally learn more than a little about their long history.

The TED-Ed lesson at the top of the post provides a brief but illuminating overview of “how Chinese characters work,” using animation to show how ancient symbols for concrete things like a person, a tree, the sun, and water became versatile enough to be combined into representations of everything else — including abstract concepts.

In the Mandarin Blueprint video just above, host Luke Neale goes deeper into the structure of the hanzi in use today. Whether they be simplified versions of mainland China or the traditional ones of Taiwan, Hong Kong, and elsewhere, they’re for the most part constructed not out of whole cloth, he stresses, but from a set of existing components. That may make a prospective learner feel slightly less daunted, as may the fact that roughly 80 percent of Chinese characters are “semantic-phonetic compounds”: one component of the character provides a clue to its meaning, and another a clue to its pronunciation. (Not that it necessarily makes deciphering them an effortless task.)

In the distant past, hanzi were also the only means of recording other Asian languages, like Vietnamese and Korean. Still today, they remain central to the Japanese writing system, but like any other cultural form transplanted to Japan, they’ve hardly gone unaltered there: the NativLang video just above explains the transformation they’ve undergone over millennia of interaction with the Japanese language. It wasn’t so very long ago that, even in their homeland, hanzi were threatened with the prospect of being scrapped in the dubious name of modern efficiency. Now, with those aforementioned almost-100,000 characters incorporated into Unicode, making them usable throughout our 21st-century digital universe, it seems they’ll stick around — even longer, perhaps, than the Latin alphabet you’re reading right now.

Related content:

What Ancient Chinese Sounded Like — and How We Know It: An Animated Introduction

Discover Nüshu, a 19th-Century Chinese Writing System That Only Women Knew How to Write

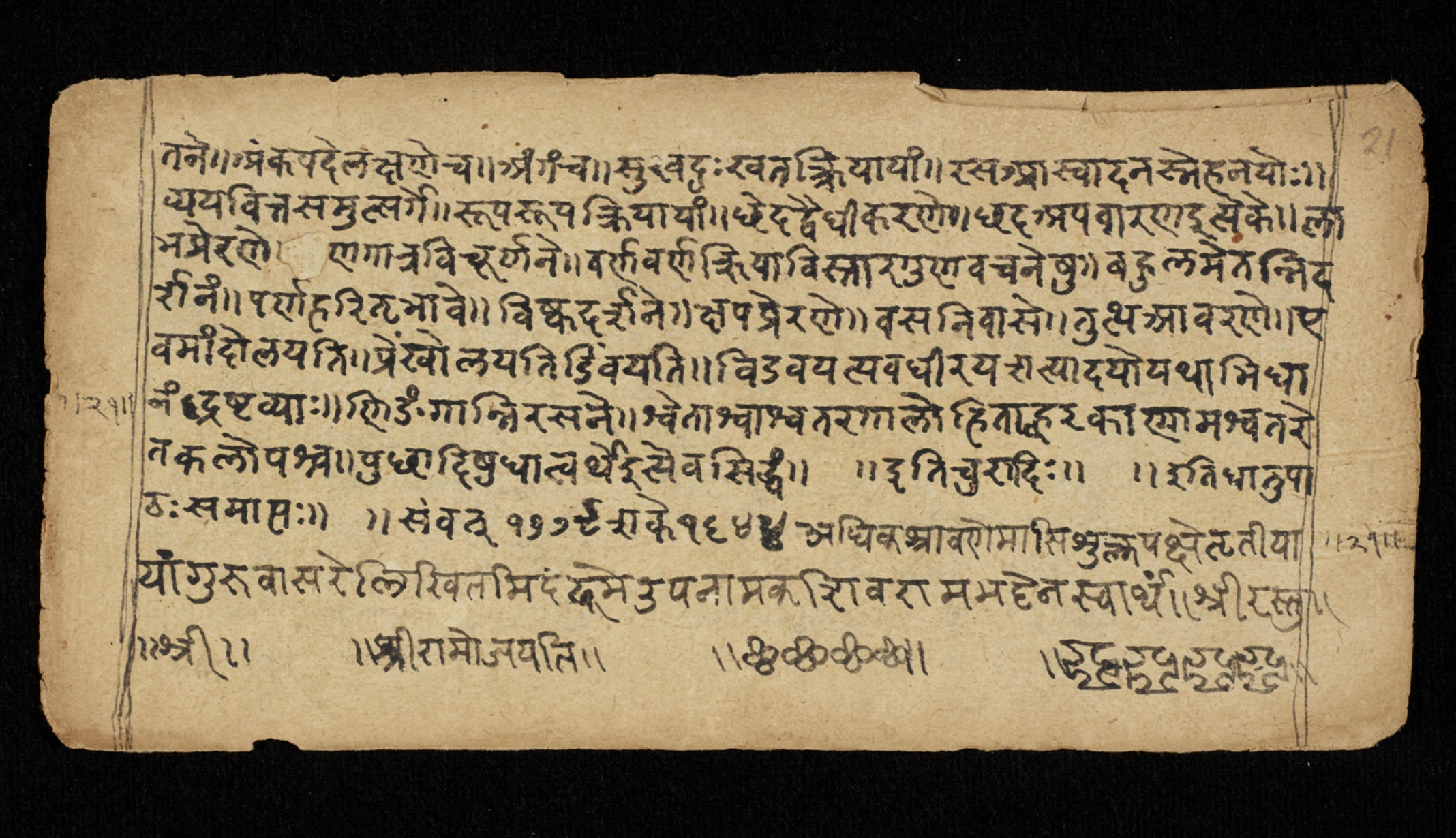

The Writing Systems of the World Explained, from the Latin Alphabet to the Abugidas of India

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on the social network formerly known as Twitter at @colinmarshall.