Women in the entertainment business who have taken a stand against racism and state violence and oppression have often found their careers ruined as a result, their albums and performances boycotted, opportunities rescinded. This, according to Nina Simone, is what happened to her after she began her fight for Civil Rights with the ferocious “Mississippi Goddam.” She continued performing in Europe until the 1990s, but her cultural stock in her own country declined after the 60s. She was largely unknown to younger generations until Lauryn Hill and later hip hop artists turned her music into a “secret weapon.”

Maybe the music of Hazel Scott will enjoy a similar revival now that her name has been returned to popular consciousness by Alicia Keys, who paid tribute to Scott at last year’s Grammys. Once the biggest star in jazz, Scott’s career was destroyed by the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) in the 1950s when a publication called Red Channels accused her of Communist sympathies. Blacklisted, she moved to Paris and performed exclusively in Europe until the mid-sixties. As with many an artist who suffered this fate during the Cold War, Scott stood accused of anti-Americanism not for any actual support of the Soviets but because she challenged racial segregation and discrimination at home.

Born in Trinidad and raised by her mother in New York City, like Simone, Scott was a classically trained child prodigy (see her play jazz-infused Liszt for World War II soldiers in the video below), whose early, sometimes violent, experiences with racism left lasting scars. She auditioned for Julliard at age 8. “When she finished,” writes Lorissa Rineheart at Narratively, “the auditions director whispered, ‘I am in the presence of a genius.” Julliard founder Frank Damrosch agreed, and she was admitted.

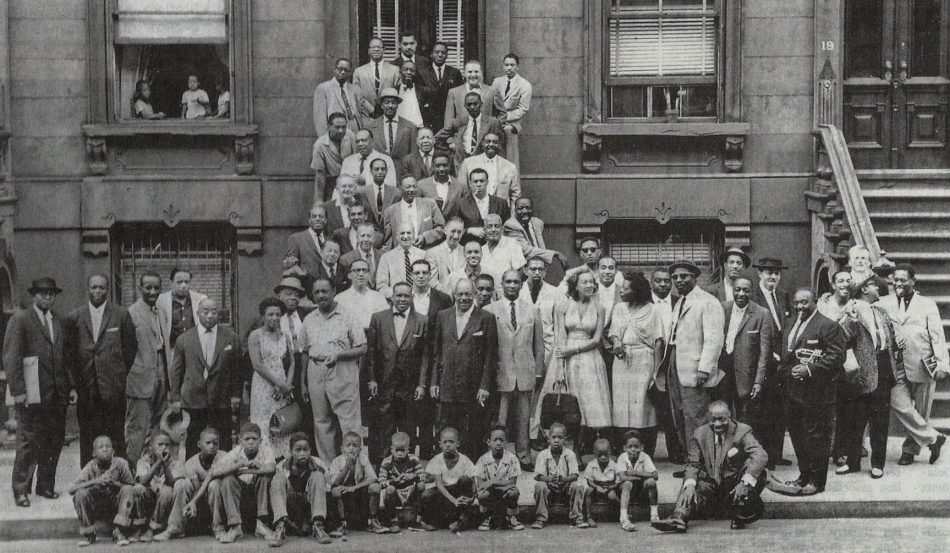

Scott’s mother Alma, herself a jazz musician, “befriended some of the Harlem Renaissance’s brightest stars,” and the young Scott grew up surrounded by the leading lights of jazz. When she got her big break at 19, taking over a three-week engagement for Billie Holiday, she immediately joined the ranks of Harlem’s finest.

As it turned out, not only was Scott a brilliant pianist, she also had a hell of a voice: deep and sonorous, comforting yet provocative — the sort of singing style that makes you want to embrace the sublime melancholy that is love and life and whiskey on a midwinter’s night.

She was flown to Hollywood in the early 40s to appear in musicals, but refused to countenance the usual racist stereotypes in film. Relegated to bit parts, she returned to New York. “I had antagonized the head of Columbia Pictures,” she wrote in her journal. “In short, committed suicide.” But she continued her activism, and her career continued to thrive. Finally, “she came to break the color barrier on the small screen” becoming the first black woman to host her own show in 1950. “Three nights a week, Scott played her signature mix of boogie-woogie, classics, and jazz standards to living rooms across America. It was a landmark moment.”

And it was not to last. That same year, Scott voluntary appeared before HUAC to answer the supposed charges against her, remaining calm in the face of hours of questioning and reading an eloquent prepared statement. “It has never been my practice to choose the popular course,” she said. “When others lie as naturally as they breathe, I become frustrated and angry.” She concluded “with one request—and that is that your committee protect those Americans who have honestly, wholesomely, and unselfishly tried to perfect this country and make the guarantees in our Constitution live. The actors, musicians, artists, composers, and all of the men and women of the arts are eager and anxious to help, to serve. Our country needs us more today than ever before. We should not be written off by the vicious slanders of little and petty men.”

Weeks later, her show was canceled “and concert bookings became few and far between,” writes her biographer Karen Chilton at Smithsonian. “The government’s suspicions were enough to cause irreparable damage to her career,” and damn her to obscurity when she deserves a place next to contemporary greats like Holiday, Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, and others. “After a decade of living abroad, she would return to an American music scene that no longer valued what she had to offer.” Learn much more about Hazel Scott in the short documentary video, “What Ever Happened to Hazel Scott,” at the top, and in Chilton’s book Hazel Scott: The Pioneering Journey of a Jazz Pianist, from Café Society to Hollywood to HUAC.

via Narratively

Related Content:

Bertolt Brecht Testifies Before the House Un-American Activities Committee (1947)

Ayn Rand Helped the FBI Identify It’s A Wonderful Life as Communist Propaganda

Watch a New Nina Simone Animation Based on an Interview Never Aired in the U.S. Before

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness