This past month, on the eve of the June 22nd feast of St Alban, the library of Trinity College Dublin announced that it had digitized the “13th century masterpiece” the Book of St Alban, a richly illustrated manuscript that “features 54 individual works of medieval art and has fascinated readers across the centuries, from royalty to renaissance scholars.”

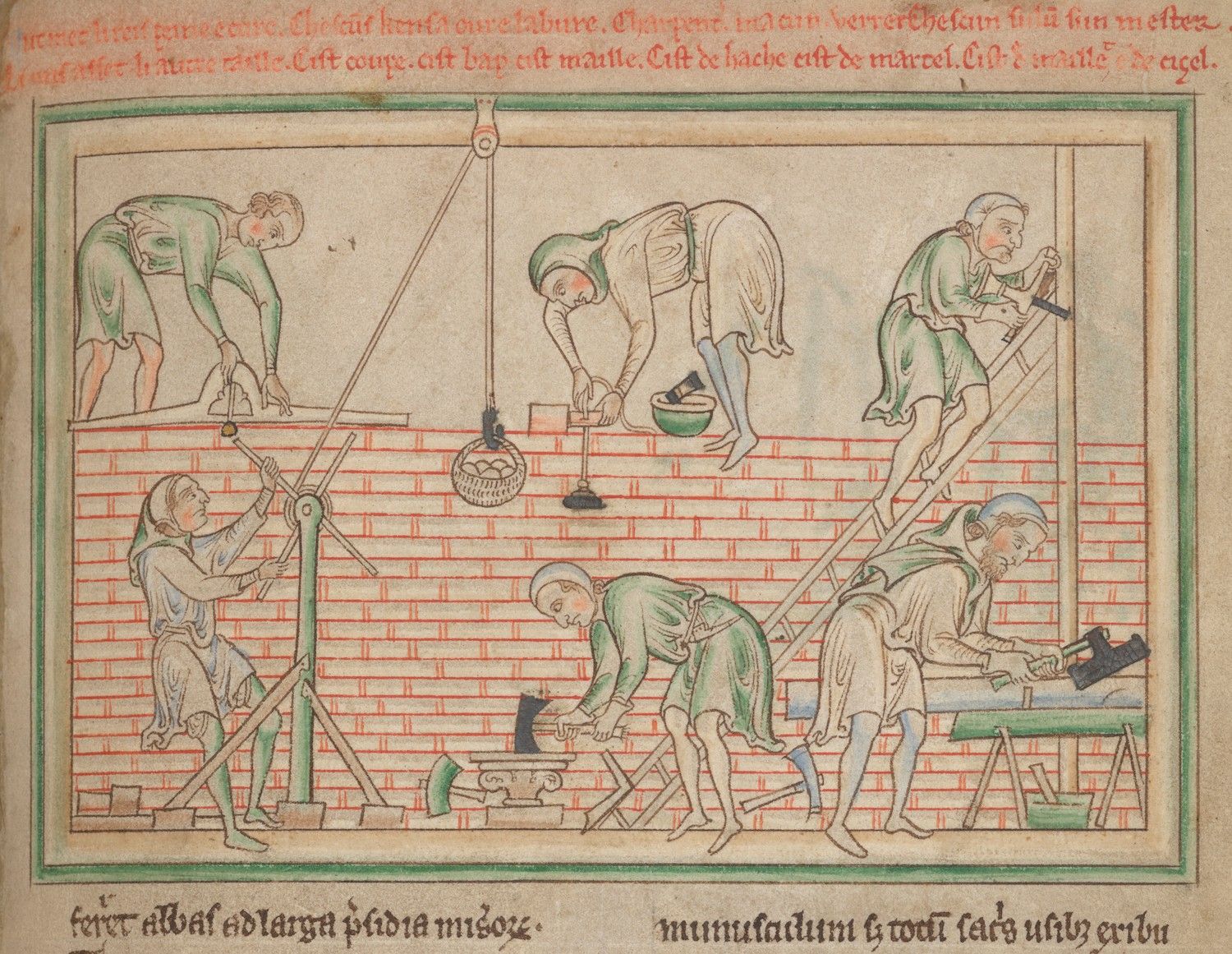

Created by the Benedictine monk Matthew Paris, the manuscript “chronicles the life of St Alban,” notes The Irish Times, “and also outlines the construction of St Alban’s Cathedral in Hertfordshire.” The text and illustrations explain the origins of a cult of St. Alban, the first English martyr, that began to spring up after his 4th century death.

According to the Venerable Bede, the English monk who wrote the Ecclesiastical History of the English People, the martyrdom of Alban involved a few miraculous events. Sentenced to die for his refusal to renounce Christianity, Alban supposedly petitioned God to dry up the River Ver so he could more quickly reach the place of his execution.

This miracle caused Alban’s Roman executioner to fall to his feet, spontaneously convert, and refuse to kill the saint. A second executioner stepped in to behead them both, whereupon this man’s eyes popped out of his head. “He who gave the wicked stroke,” writes Bede, “was not permitted to rejoice over the deceased; for his eyes dropped upon the ground together with the blessed martyr’s head.”

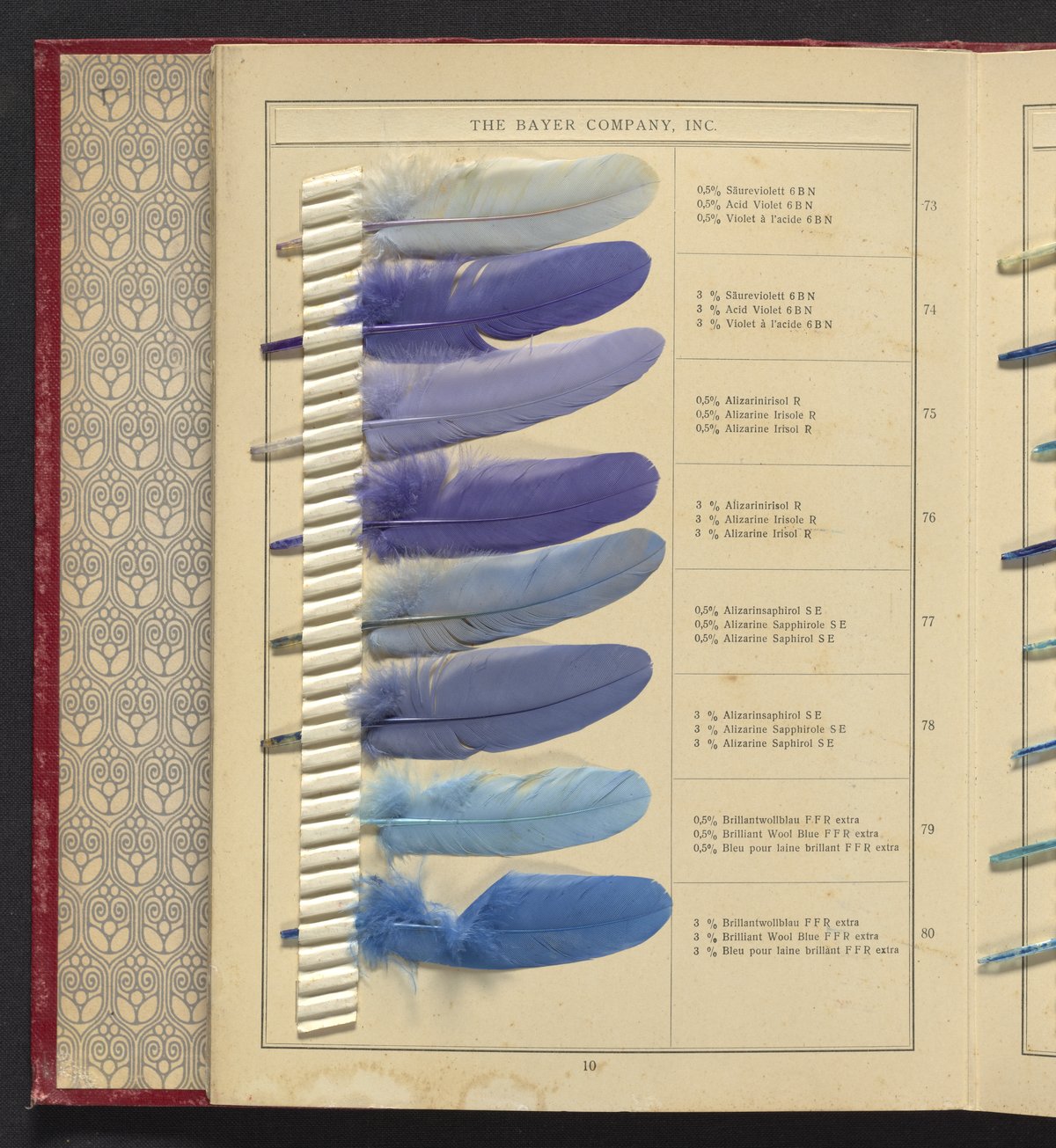

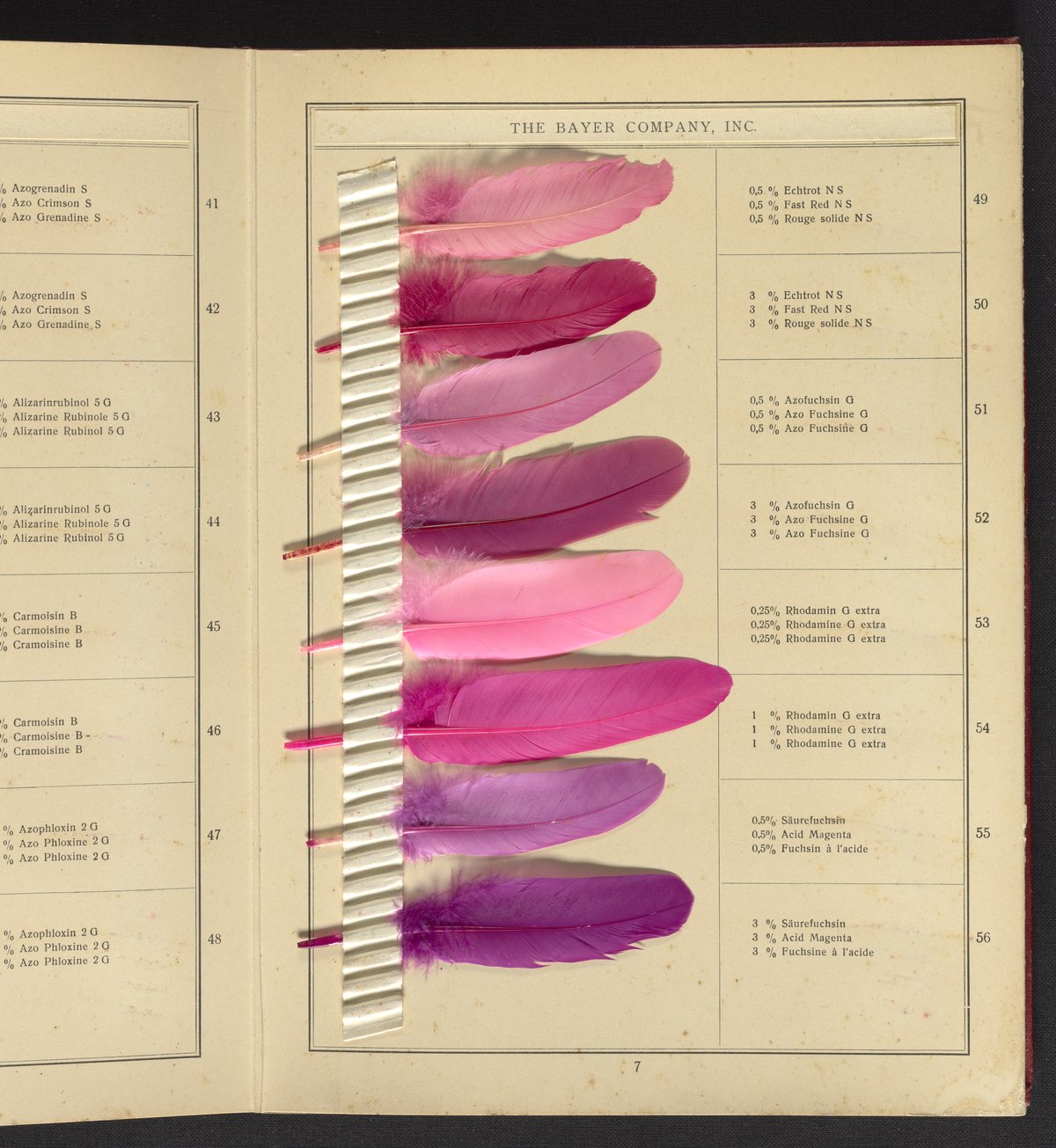

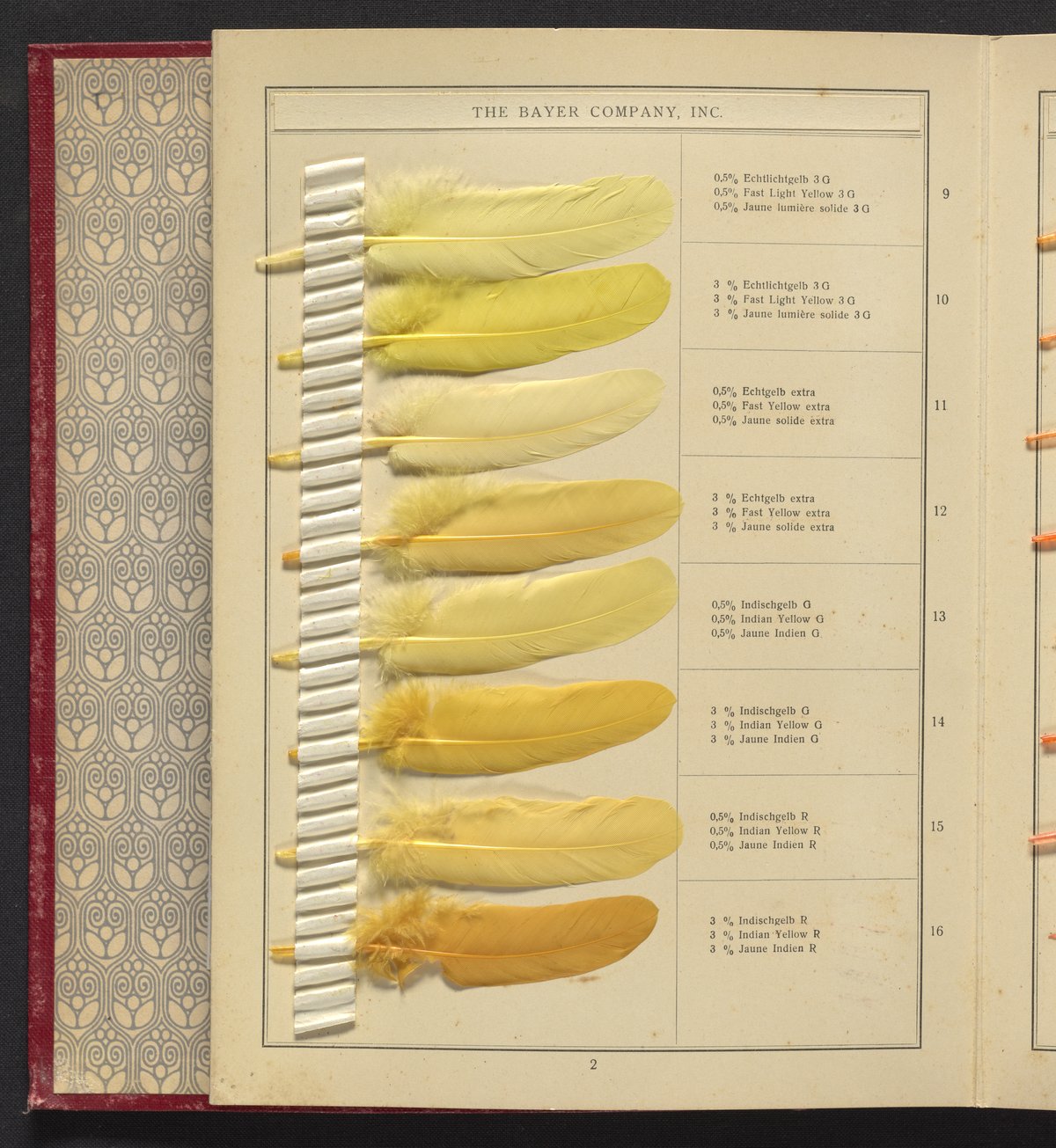

In the illustration of this grisly story (top) from the manuscript, we see the executioner holding his eyes in his hand, and Alban’s head appears to have been caught by the hair on a tree branch above. Another illustration, further up, shows a character named Heraclius making off with Alban’s head.

In a later legend, Alban’s head rolled to the bottom of Holywell Hill, and a well sprang from where it came to rest. On the supposed site of Alban’s execution now stands St Albans Cathedral, once St Albans Abbey, where the Book of St Albans remained for 300 years until Henry VIII dissolved Britain’s monasteries in 1539.

The book is written in both Latin and Anglo-Norman French, “which made it accessible to a wider secular audience including educated noble women,” Trinity College’s Caoimhe Ni Lochlainn writes. “It was borrowed by noble ladies of the period, including the King’s sister-in-law Countess of Cornwall, Sanchia of Provence, and others.”

The manuscript eventually made its way to Trinity College Dublin in 1661, where it has remained ever since, and where its “mostly framed narrative scenes” have been admired by a select few. Now everyone can access the book and its illustrations, made with a “tinted drawing technique,” Lochlainn notes, “where outlined drawings are highlighted with colored washes from a limited palette. This technique was distinctly English, dating back to the Anglo Saxon art of the 10th century.”

See all the grisly details of this fascinating artifact at Trinity College Dublin’s Digital Collections, and learn more about the manuscript in the video just above.

Related Content:

The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Has Been Digitized and Put Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness