The first subway train, as we know such things today, entered service in 1890. Its path is now part of the Northern line of the London Underground, itself the first urban metro system. The success of the Tube, as it’s commonly known, didn’t come right away; the whole thing was on the brink of failure, in fact, before creations like 1914’s Wonderground Map of London Town aided its public understanding and bolstered its public image.

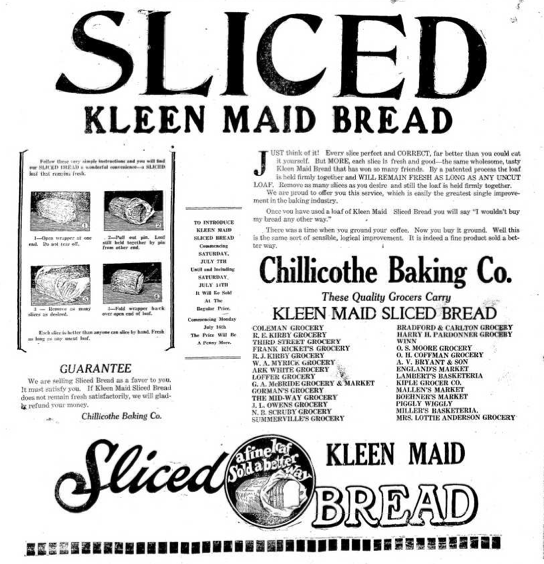

At the time, Britain still commanded a great empire with London as its capital; the Wonderground Map placed the London Underground in the context of the city, making legible the still fairly novel concept of an underground train system with copious whimsical detail.

Nor was the Roman Empire anything to sneeze at, even during the fourth and fifth centuries after its decline had set in. Though it came up with some still-impressive inventions, including long-lasting concrete and monumental aqueducts, the technology to build and operate a subway system still lay some way off.

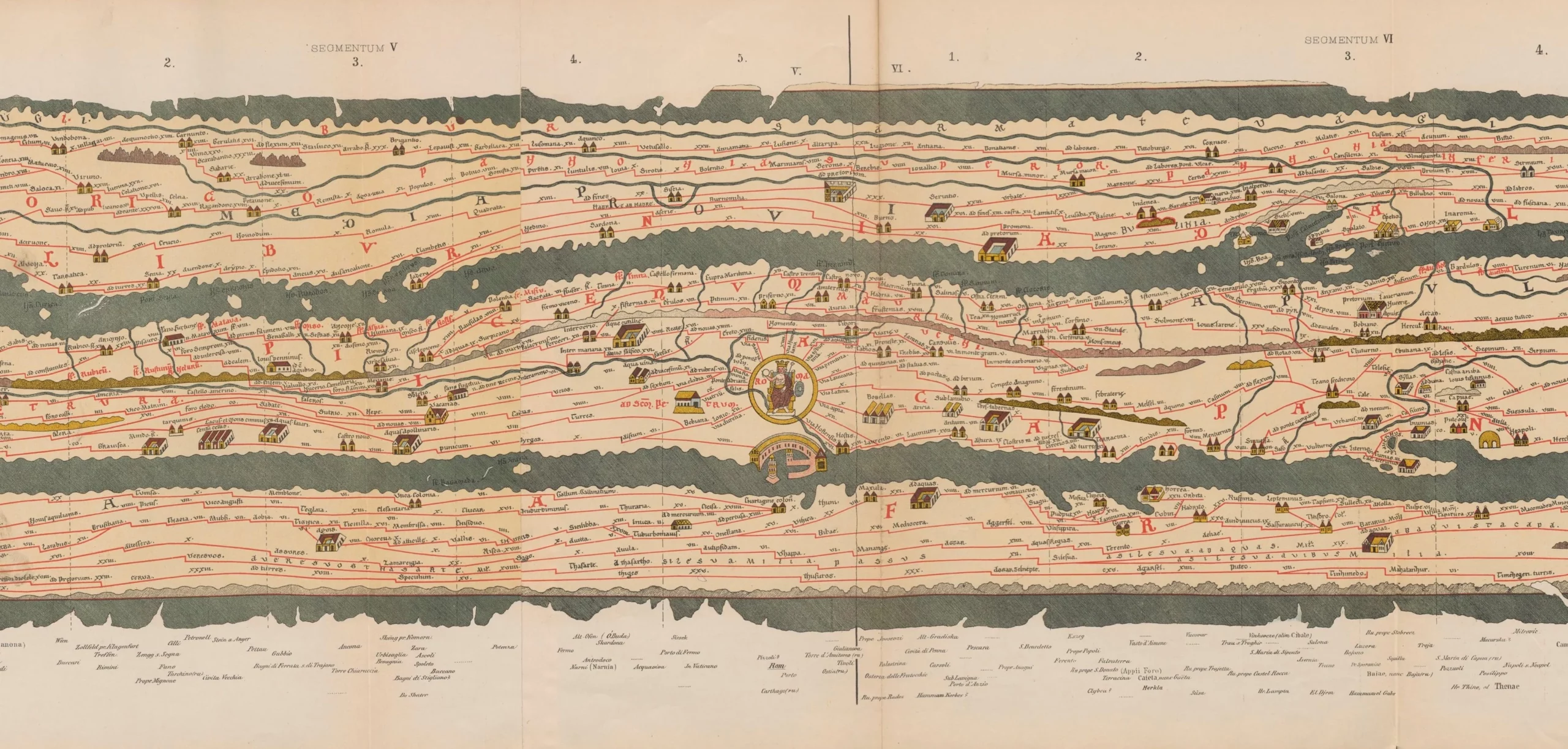

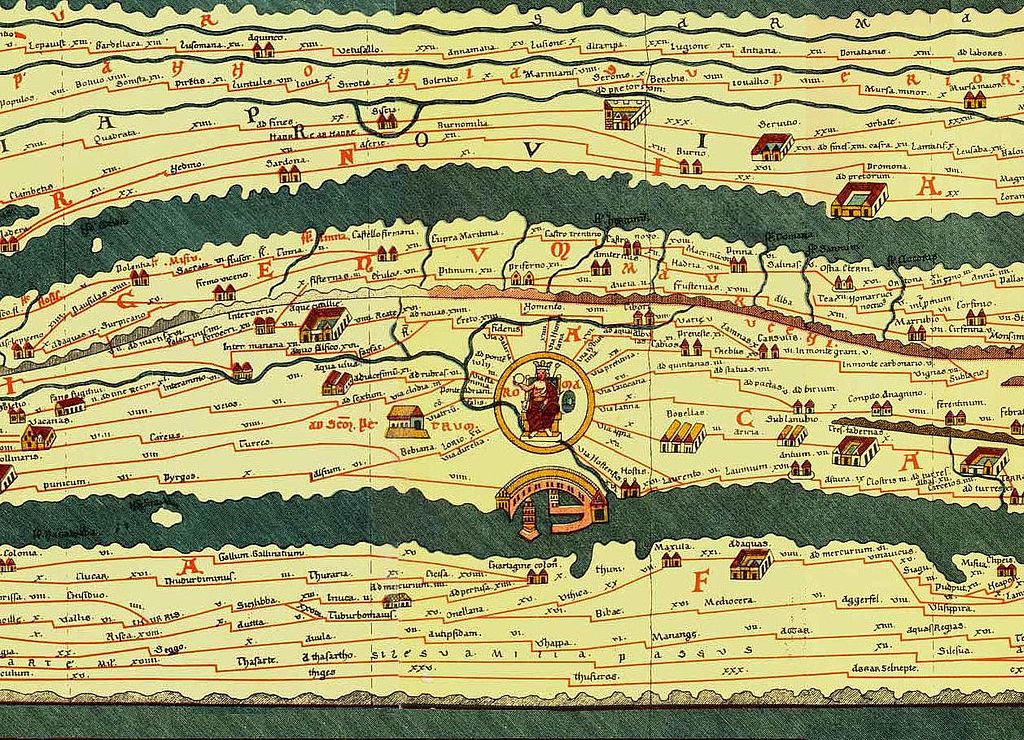

But that didn’t stop Marcus Vipsanius Agrippa, a general, architect, and friend of emperor Augustus, from commissioning a map of the empire that read more or less like Massimo Vignelli’s 1972 map of the New York subway. That ambitious work of cartography, historians now believe, inspired the Tabula Peutingeriana, which survives today as the only large world map from antiquity. The video above from Youtuber Jeremy Shuback approaches the Tabula Peutingeriana as “the first transit map,” despite its dating from the thirteenth century, and even then probably being a copy of a fourth- or fifth-century original.

While the Roman Empire didn’t have electric trains and payment cards, they did, of course, have transit: the word descends from the Latin transire, “go across.” Many a Roman had to go across, if not the whole empire, then at least large stretches of it. In theory, they would have found a map like Tabula useful, with its simplification of geography in order to emphasize city-to-city connections. But that wasn’t its primary purpose: as Shuback puts it, this oversized map of all lands dominated by the Romans was “made to brag.” Whoever owned it surely wanted to imply that they possessed not just a map, but the world itself.

Related content:

A Wonderful Archive of Historic Transit Maps: Expressive Art Meets Precise Graphic Design

The Roman Roads of Britain Visualized as a Subway Map

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.