We don’t hear the phrase “very rich hours” as much as we used to, back when it was occasionally employed in the headlines of magazine articles or the titles of novels. Today, it’s much to be doubted whether even one in a hundred thousand of us could begin to identify its referent — or at least it was much to be doubted until an elaborate New York Times online feature appeared just last week. Written by art critic Jason Farago, “Searching for Lost Time in the World’s Most Beautiful Calendar” takes a close look at the Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry, a late-medieval illuminated manuscript created (between 1412 and 1416) for the bibliophilic John, Duke of Berry by a trio of Flemish artists known as the Limbourg brothers.

The word “hours” in the title refers not to units of time, exactly, but to the prayers that believers must speak at certain hours: this is a book of hours, a hugely popular form of manuscript in the Middle Ages. But compared to most surviving books of hours, Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry is, well, very rich indeed.

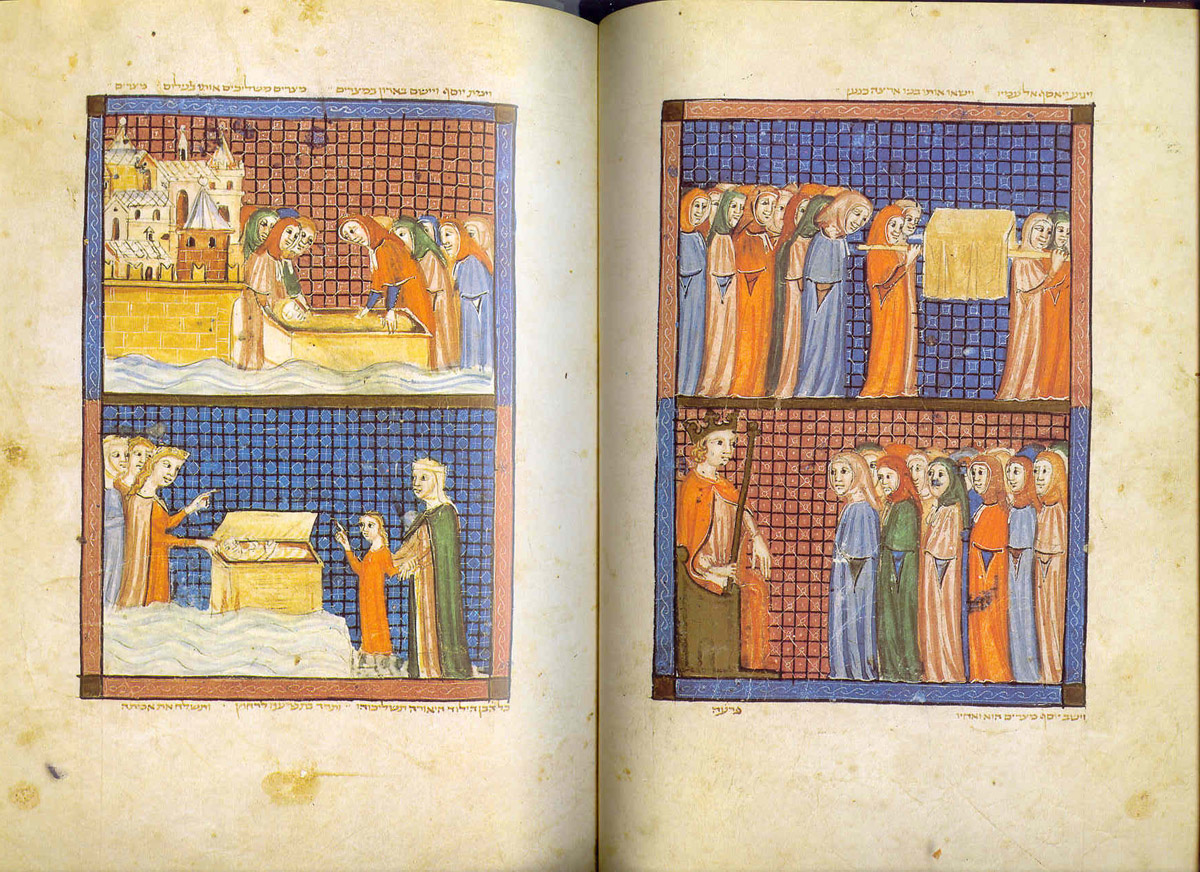

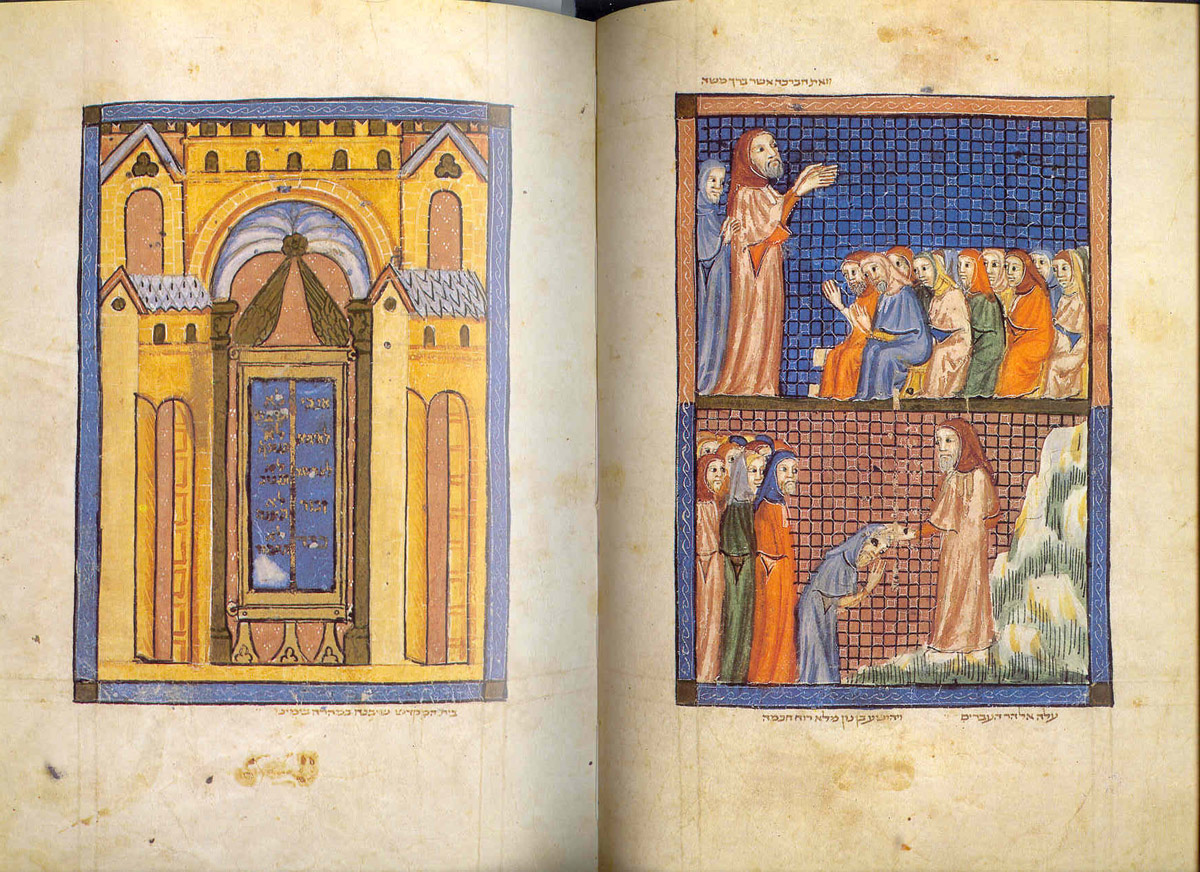

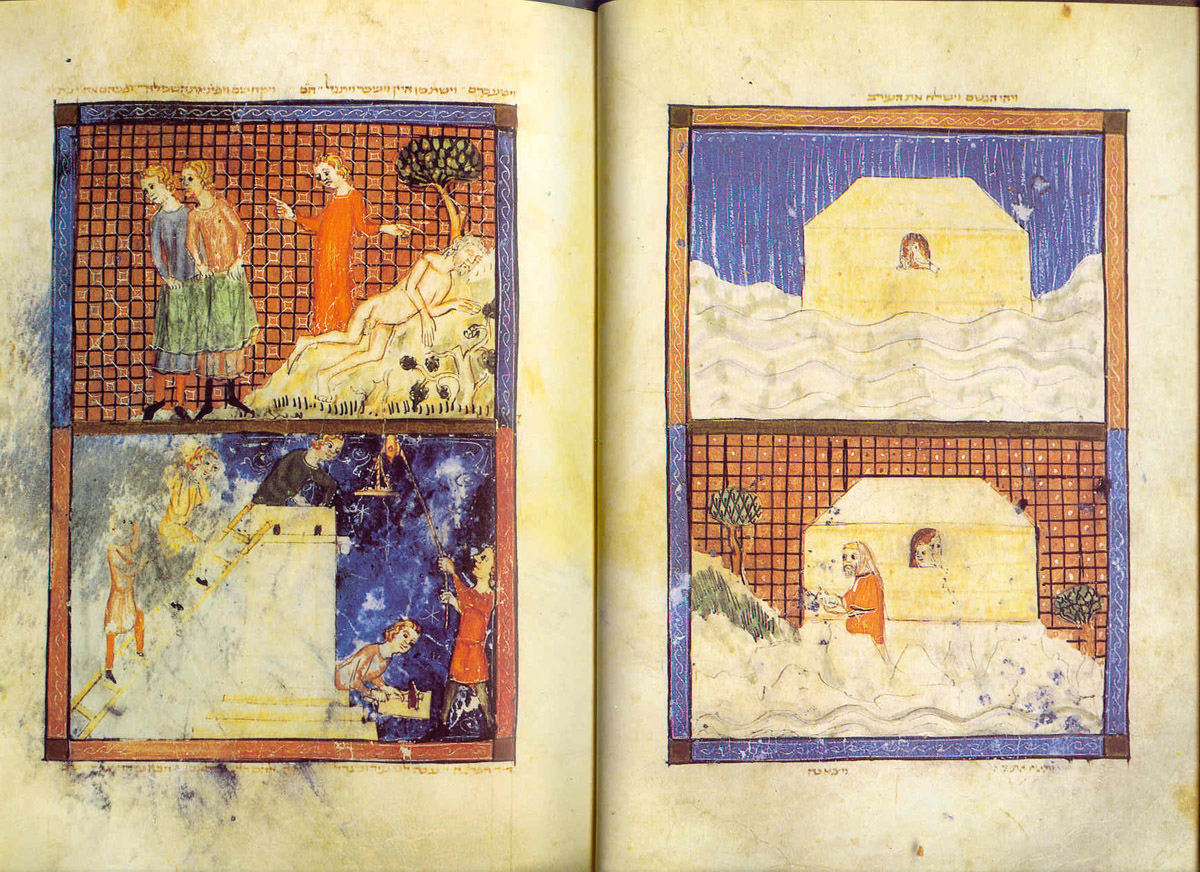

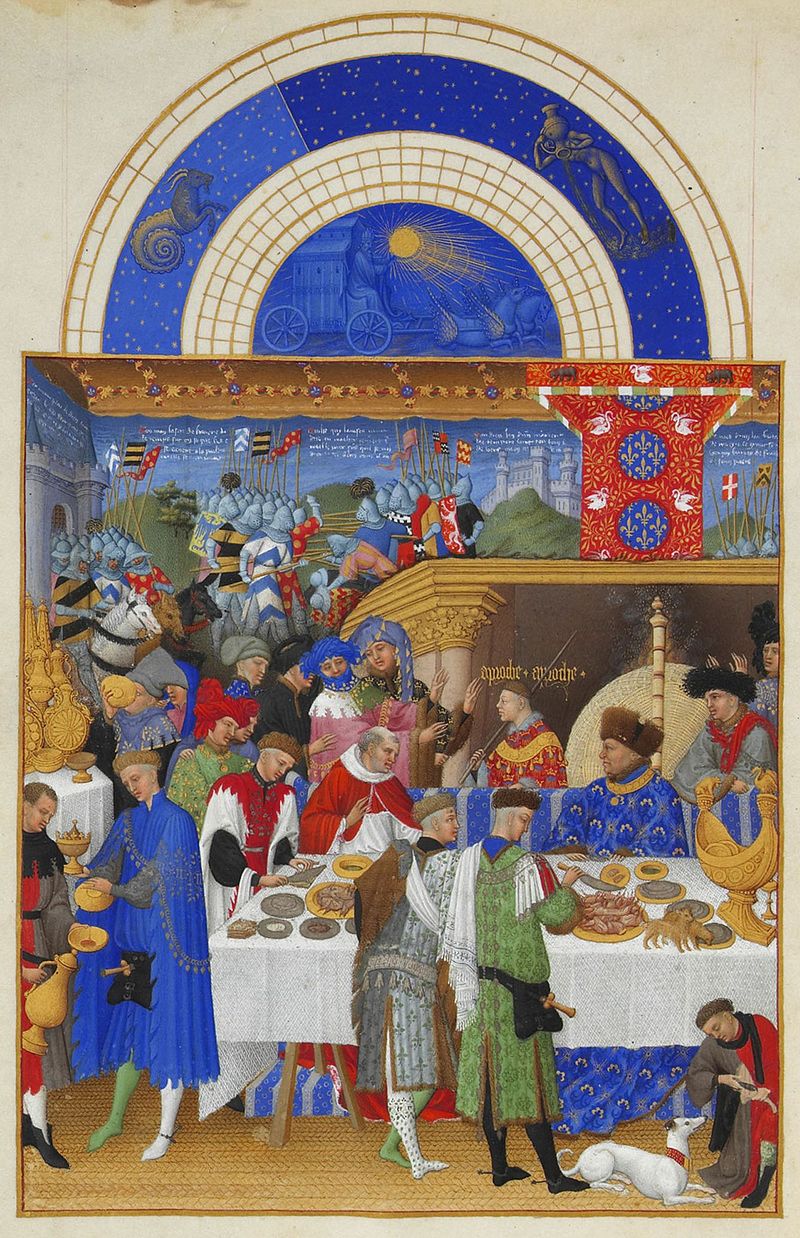

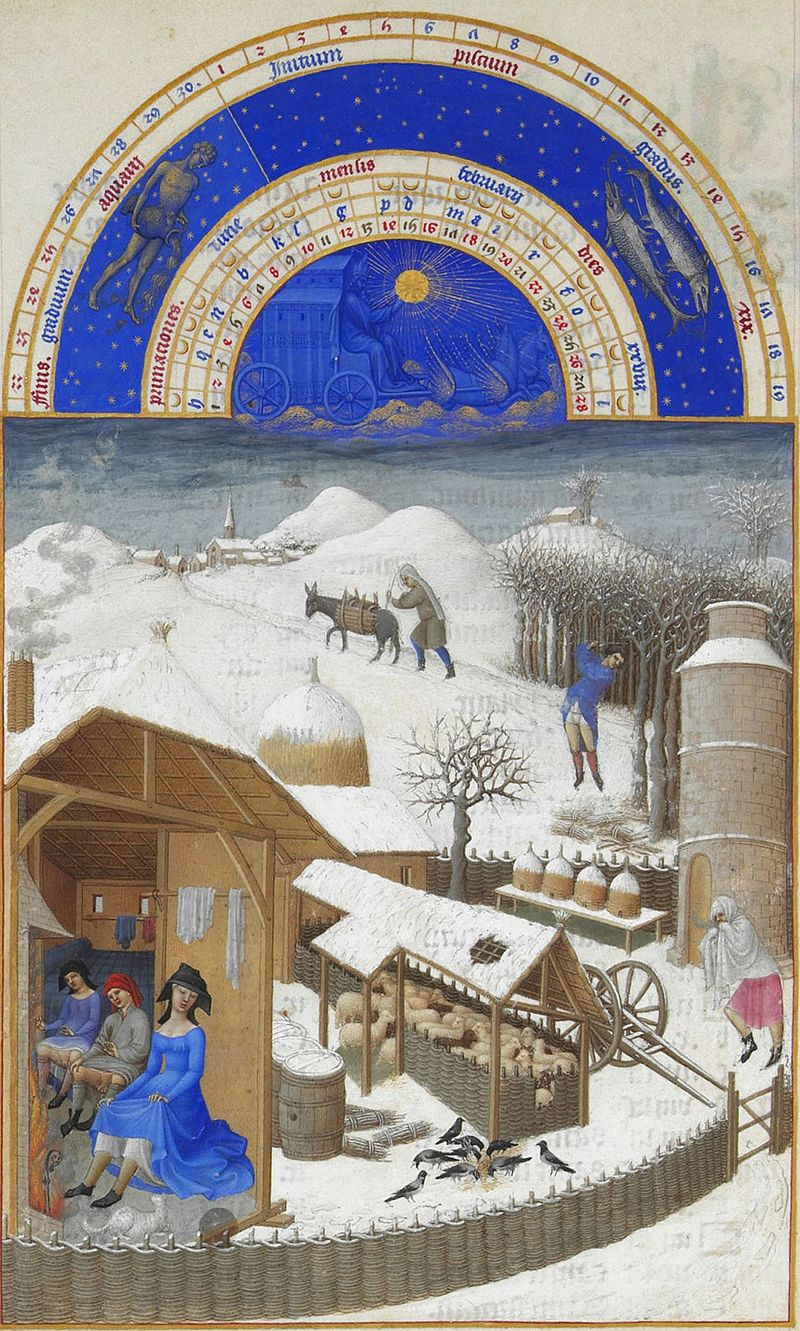

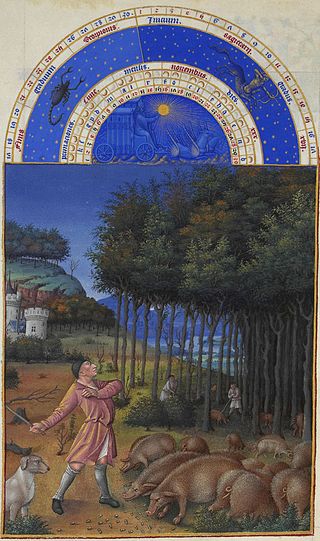

Farago calls it “the finest surviving manuscript of the fifteenth century, a monument of International Gothic book arts. Really, the thing is just stupefying. Its pictures combine astounding detail with exuberant, sometimes irrational spatial organization.” But “like every book of hours, it opens with a calendar. And here, on its first 12 spreads — with one full-page illustration per month — the Limbourgs did their most painstaking work.”

Here we have just five of the images from the calendar at the head of the Très Riches Heures. You can see the rest at the site of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which offers its “intimate Northern vision of nature with Italianate modes of figural articulation” in downloadable digital form. These detailed images constitute a window into not just medieval life (or at least an idealized version thereof), but also the medieval relationship to time. “Time appears to be a cycle,” writes Farago. “It repeats year after year.” And “months rather than years were the meat of these cycles. Seasons. Harvests. Feasts. Constellations.” All this “could be perceived with the senses. In snowfall, in star signs. In the bright colors you wore in May, in the furs you wore in December.”

On top of this palpably cyclical experience of time, monotheistic religions introduced the notion that “time progressed onward,” and indeed “offered a one-way ticket to the end of days.” Coexisting in the medieval mind, these two contrasting modes of perception gave rise to the sort of calendars created and used in that era. No finer example exists than the Très Riches Heures, created as it was not long — at least in historical time — before the approach of modernity, with its ever more finely divided and rigorously calibrated chronometric regimes. Our hours are much more clearly demarcated than the Duke of Berry’s; whether they’re richer is another question entirely.

Visit the New York Times’ feature on the beautiful medieval manuscript here. If you’re interested in delving deeper, also see the free book (courtesy of the Met Museum) The Art of Illumination: The Limbourg Brothers and the Belles Heures of Jean de France, Duc de Berry.

Related content:

The Medieval Masterpiece the Book of Kells Has Been Digitized and Put Online

Behold the Codex Gigas (aka “Devil’s Bible”), the Largest Medieval Manuscript in the World

Why Butt Trumpets & Other Bizarre Images Appeared in Illuminated Medieval Manuscripts

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.