André Hörmann and Anna Samo’s short animation, Obon, opens on a serene scene — a quiet forest, anda red torii gate framing moonlight on the water.

But then we notice that the water is choked with bodies, victims of the bombing of Hiroshima.

Akiko Takakura, whose reminiscences inspired the film, arrived for work at the Hiroshima Bank just minutes before the Enola Gay dropped the atomic bomb “Little Boy” over the city, killing some 80,000 instantly.

Takakura-san, who had been cleaning desks and mooning over a cute co-worker with her fellow junior bank employee Satomi Usami when the bomb hit, was one of the 10 people within a radius of 500 meters from ground zero to have survived .

(Usami-san, who fought her way out of the wreckage with her friend’s assistance, later succumbed to her injuries.)

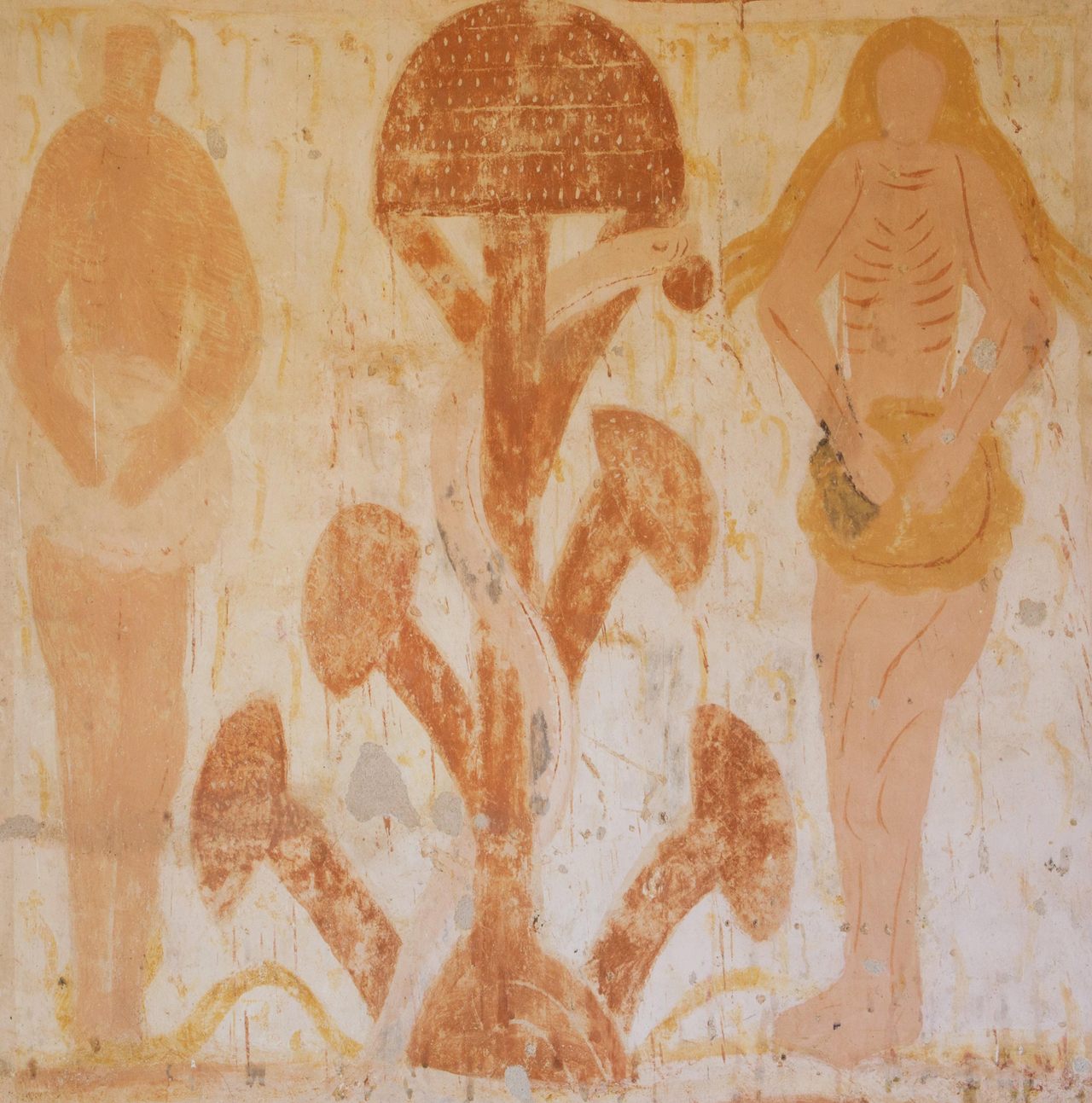

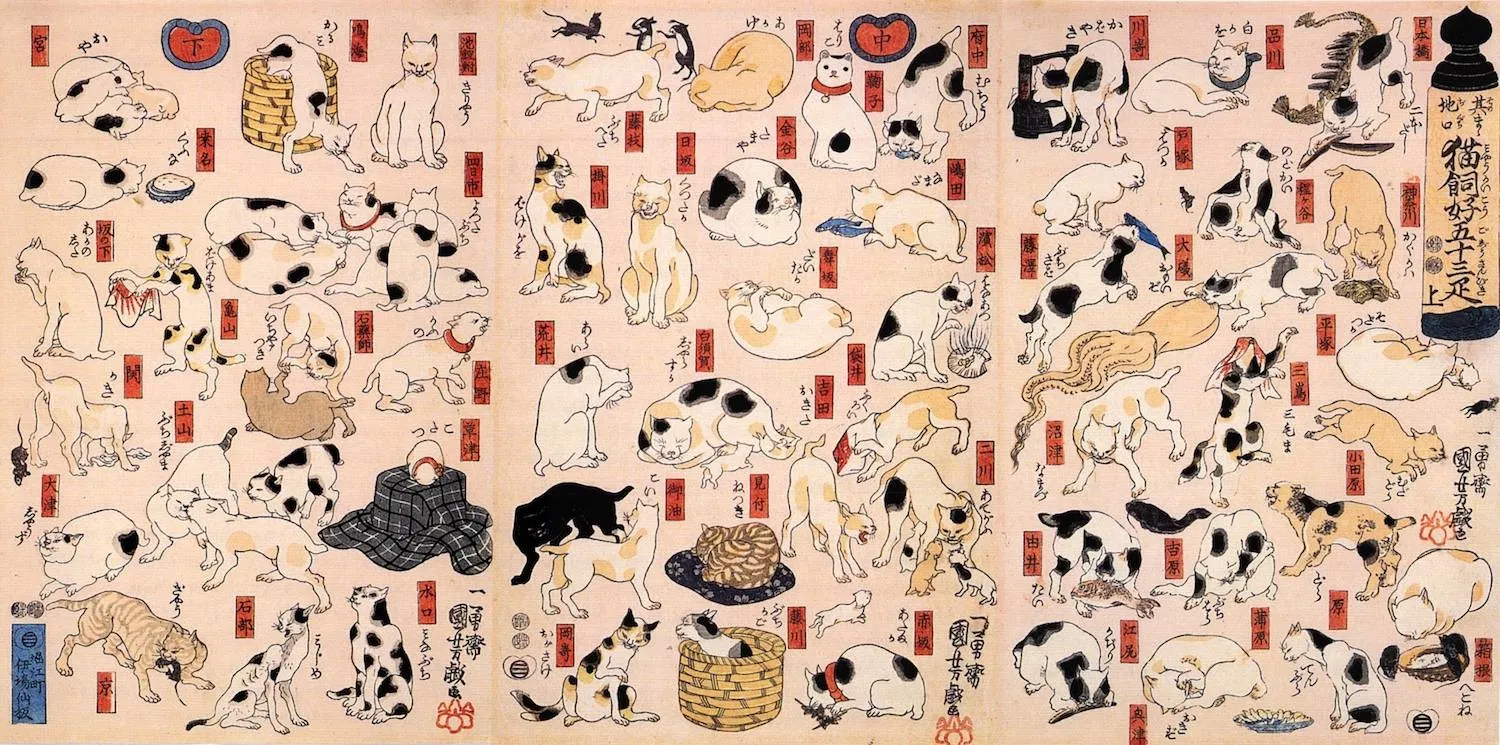

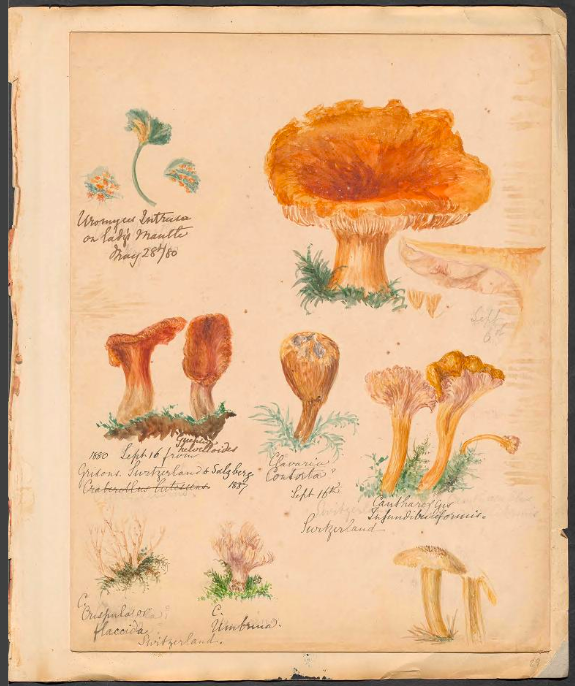

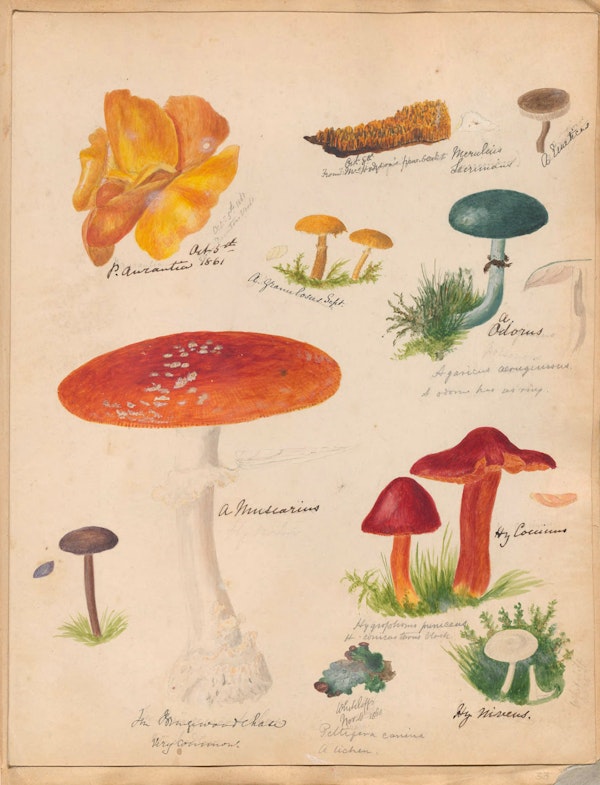

Animator Samo, whose style harkens to traditional woodcuts, based her depiction of the horrors confronting the two young women when they emerge from the bank on the drawings of survivors:

Without craft or artistry to hide behind, the drawings told stories unfiltered, made me hear shaking voices saying: this is what happened to us.

Takakura-san attempted to capture one such image in a 1974 drawing:

I saw one corpse with burning fingers. Her hand was raised and her fingers were on fire, blue flames burning them down to stumps. A light charcoal-colored liquid was oozing onto the ground. When I think of those hands cradling beloved children and turning the pages of books, even now my heart fills with a deep sadness.

Takakura-san was 84 when writer/director Hörmann traveled to Japan to meet with historians, nuclear scientists, peace researchers and elderly survivors of the atomic bomb. Over the course of three 90 minute sessions, he noticed a quality that set her apart from the other survivors he interviewed :

…the stories that she told me there was always a glimmering light of hope in the midst of all of the horror. For me, it was a sigh of relief to have this moment of hope and peace, it was beautiful. It is impossible to just tell a story that is all pain. Ms. Takakura’s story was a way for me to look at this dark piece of history and not be emotionally crushed.

Her perspective informs the film, which travels backward and forward throughout time.

We meet her as a tiny, kimono-clad old woman in modern day Japan, whose face now bears a strong resemblance to her father’s. Her back is crisscrossed with scars of the 102 lacerations she sustained on the morning of August 6, 1945.

We then see her as a little girl, whose father, “a typical man from Meiji times, tough and strict,” is unable to express affection toward his daughter.

This changed when the 19-year-old was reunited with her family after the bombing, and her father asked for forgiveness while tenderly bathing her burned hands.

To Hörmann this “tiny moment of happiness” and connection is at the heart of Obon.

Animator Samo wonders if Takakura-san would have achieved “peace with the world that was so cruel to her” if her father hadn’t tended to her wounded hands so gently:

What does an act of love in a moment of despair mean? Can it allow you to you go on with a normal life, drink tea and cook rice? If you have seen so much death, can you still look people in the eyes, get married and give birth to children?

The film takes its title from the annual Buddhist holiday to commemorate ancestors and pay respect to the dead.

As an old woman, Takakura-san tends to the family altar, then travels with younger celebrants to the river for the release of the paper lanterns that are believed to guide the spirits back to their world at the festival’s end.

The face that appears in her glowing lantern is both her father’s and a reflection of her own.

Read an interview with Akiko Takakura here.

To Children Who Don’t Know the Atomic Bomb

by Akiko Takakura

8:15 a.m. on August 6, 1945,

a very clear morning.

The mother preparing her baby’s milk,

the old man watering his potted plants,

the old woman offering flowers at her Buddhist altar,

the young boy eating breakfast,

the father starting work at his company,

the thousands walking to work on the street,

all died.

Not knowing an atomic bomb would be dropped,

they lived as usual.

Suddenly, a flash.

“Ah ~

Just as they saw it,

people in houses were shoved over and smashed.

People walking on streets were blown away.

People were burned-faces, arms, legs-all over.

People were killed, all over

the city of Hiroshima

by a single bomb.

Those who died.

A hundred? No. A thousand? No. Ten thousand?

No, many, many more than that.

More people than we can count

died, speechless,

knowing nothing.

Others suffered terrible burns,

horrific injuries.

Some were thrown so hard

their stomachs ripped open,

their spines broke.

Whole bodies filled with glass shards.

Clothes disappeared,

burned and tattered.

Fires came right after the explosion.

Hiroshima engulfed in flames.

Everyone fleeing, not knowing where

they were or where to go.

Everyone barefoot,

crying tears of anger and grief,

hair sticking up, looking like Ashura*,

they ran on broken glass, smashed roofs

along a long, wide road of fire.

Blood flowed.

Burned skin peeled and dangled.

Whirlwinds of fire raged here and there.

Hundreds, thousands of fire balls

30-centimeters across

whirled right at us.

It was hard to breathe in the flames,

hard to see in the smoke.

What will become of us?

Those who survived, injured and burned,

shouted, “Help! Help!” at the top of their lungs.

One woman walking on the road

died and then

her fingers burned,

a blue flame shortening them like candles,

a gray liquid trickling down her palms

and dripping to the ground.

Whose fingers were those?

More than 50 years later,

I remember that blue flame,

and my heart nearly bursts

with sorrow.

Related Content

Haunting Unedited Footage of the Bombing of Nagasaki (1945)

Watch Chilling Footage of the Hiroshima & Nagasaki Bombings in Restored Color

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.