Most of us have doodled in the margins of our books at one time or another, and some of us have even dared to write our own names. But very of few us, presumably, would have expected our handiwork to be marveled at twelve centuries hence. Yet that’s just what has happened to the marginalia left by a medieval Englishwoman we know only as Eadburg, who some time in the eighth century committed her name — as well as other symbols and figures — to the pages of a Latin copy of the Acts of the Apostles.

Eadburg did this with such secrecy that only advanced twenty-first century technology has allowed us to see it at all. That the readers in the Middle Ages sometimes jotted in their manuscripts isn’t unheard of.

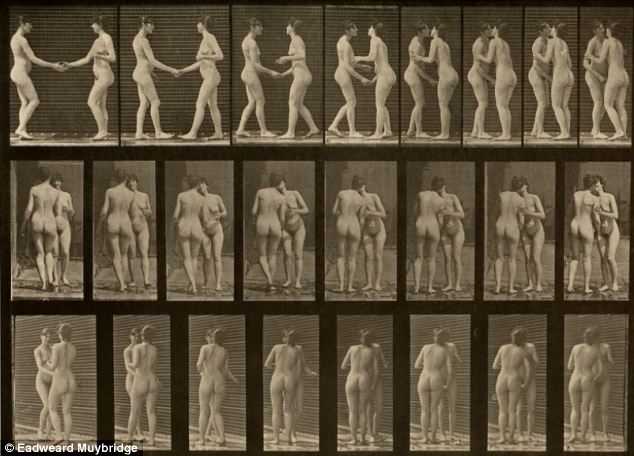

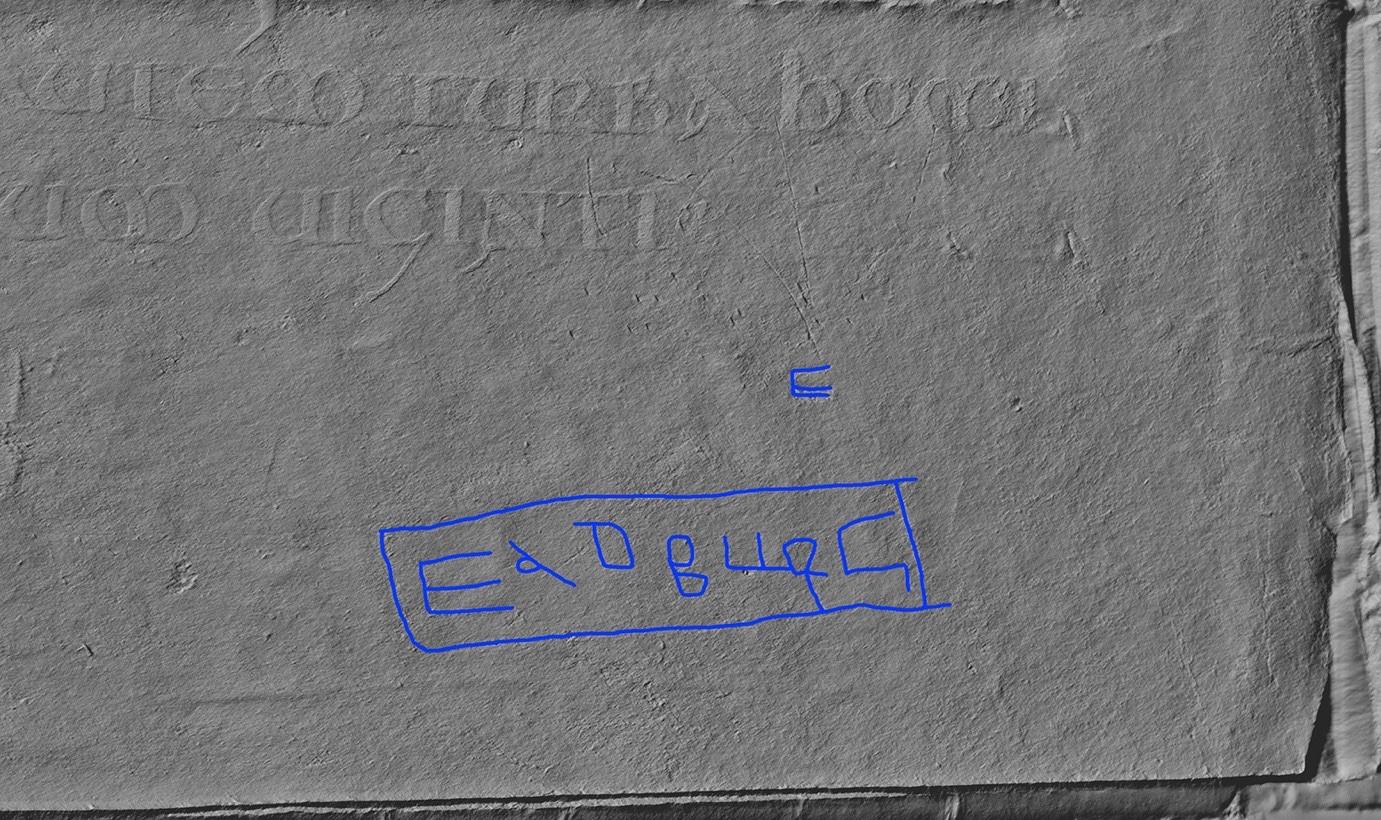

But unlike most of them, Eadburg seems to have favored a drypoint stylus — i.e., a tool with nothing on it to leave a clear mark — which would have made her writing nearly impossible to notice with the naked eye. To see all of them necessitated the use of a technique called “photometric stereo,” which Oxford University’s Bodleian Library Senior Photographer John Barrett explains in this blog post.

The scanning process collects images that “map the direction and height of the original’s surface, and are processed into renders showing only the relief of the original with the tone and color removed.” Subsequent steps of filtering and enhancement result in a digital reproduction of “the three-dimensional surface of the page,” which, with the proper enhancements, finally allows drypoint inscriptions to be seen. Eadburg’s name, reports the Guardian’s Donna Ferguson, was found “passionately etched into the margins of the manuscript in five places, while abbreviated forms of the name appear a further ten times.”

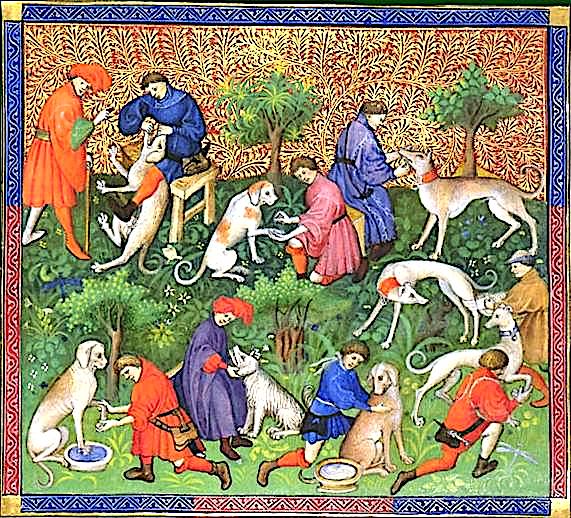

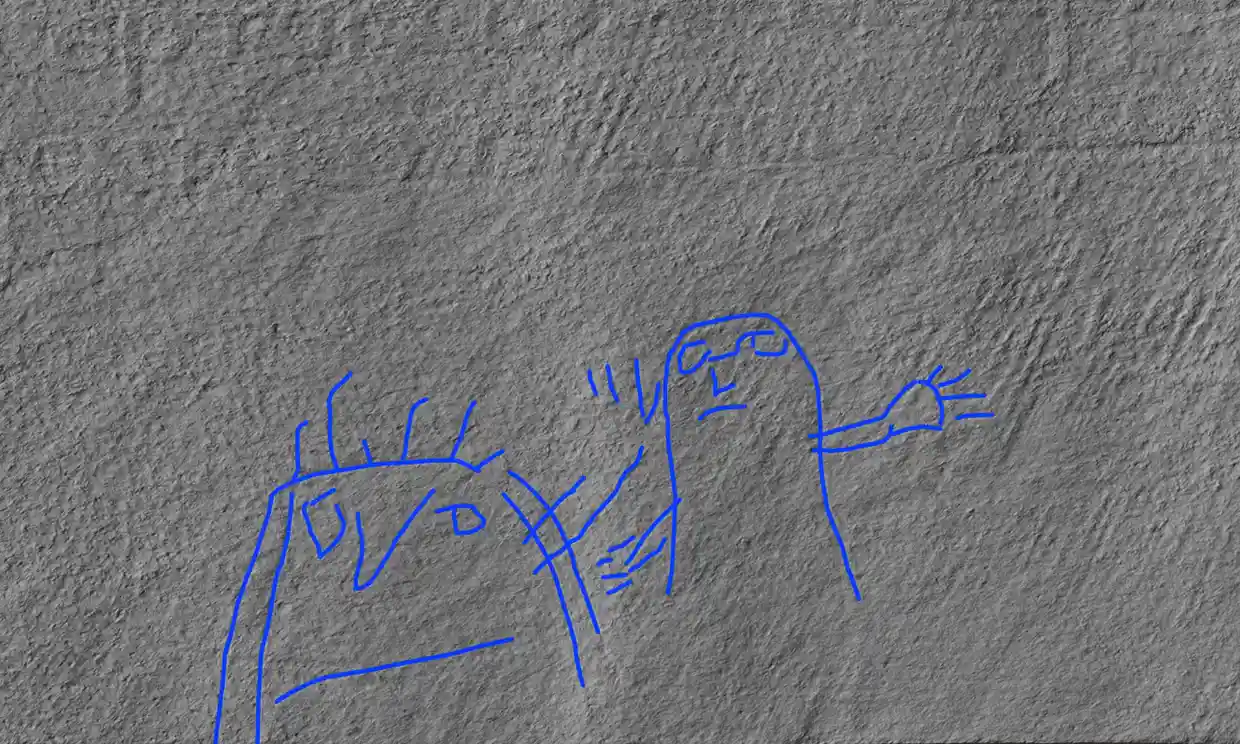

Other new discoveries in the manuscript’s pages include “tiny, rough drawings of figures — in one case, of a person with outstretched arms, reaching for another person who is holding up a hand to stop them.” What Eadburg meant by it all remains a matter of active inquiry, but then, so does her very identity. “Charter evidence suggests that a woman called Eadburg was abbess of a female religious community at Minster-in-Thanet, in Kent from at least 733 until her death sometime between 748 and 761,” writes Barrett, but she wasn’t the only Eadburg who could’ve possessed the book. All this contains a lesson for today’s marginalia-makers: if you’re going to sign your name, sign it in full.

Related content:

When Medieval Manuscripts Were Recycled & Used to Make the First Printed Books

160,000+ Medieval Manuscripts Online: Where to Find Them

Discover Nüshu, a 19th-Century Chinese Writing System That Only Women Knew How to Write

Ayn Rand Trashes C.S. Lewis in Her Marginalia: He’s an “Abysmal Bastard”

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.