New Yorkers can be a maddeningly closed-mouth bunch, selfishly guarding our secret haunts lest they be overrun with newcomers and tourists…

But there’s not much we can do to deflect interest from Grand Central Teminal’s whispering gallery, a wildly popular acoustic anomaly in the tiled passageway just outside its famous Oyster Bar.

So we invite you to bring a friend, position yourselves in opposite corners, facing away from each other, and murmur your secrets to the wall.

Your friend will hear you as clearly as if you’d been whispering directly into their ear…and 9 times out of 10, a curious onlooker will approach to ask what exactly is going on.

Initiate them!

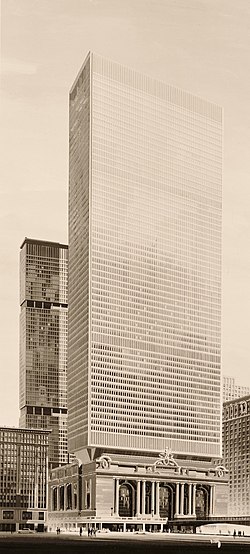

Sharing secrets of this order cultivates civic pride, a powerful force that Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis harnessed when developers threatened to obscure Grand Central’s beauty with a towering addition designed by Modernist architect Marcel Breuer.

Onassis wrote to Mayor Abraham Beame in 1975, hoping to enlist him in the fight to spare midtown Manhattan’s jewel from an affront that the Landmarks Preservation Commission called an “aesthetic joke:”

Is it not cruel to let our city die by degrees, stripped of all her proud moments, until there is nothing left of all her history and beauty to inspire our children? If they are not inspired by the past of our city, where will they find the strength to fight for her future?

The Supreme Court sealed the deal in Grand Central’s favor in Penn Central Transportation Co. vs. New York City, a (pardon the pun) landmark decision that ensured future generations could discover the Beaux-Arts treats historian Anthony Robins, author of Grand Central Terminal: 100 Years of a New York Landmark, divulges above.

Hopefully, you’ll be inspired to budget a few extra minutes to hunt for Caducei and Vanderbilt family acorns next time you’re grabbing a Metro-North commuter train.

(Amtrak’s long distance lines operate out of Penn Station…)

Spend some time in Grand Central’s iconic Main Concourse.

Gaze up toward the great arched windows to see if you can catch a tiny human figure behind the glass bricks, passing along one of the high up hidden catwalks connecting office buildings anchoring Grand Central’s corners.

Perhaps you’ll be privy to some intrigue near the famous four-sided clock, a time-honored rendez-vous spot that’s appeared in numerous films, including The Godfather, Men in Black, and North by Northwest.

Admire the upside down and backwards constellations adorning the vaulted ceiling, marveling that it not only took five men — architect Whitney Warren, artist Paul Helleu, muralist J. Monroe Hewlett, painter Charles Basing, and astronomer Harold Jacoby — to get it wrong, their celestial boo-boo has been embraced during subsequent renovations.

If your wallet’s as fat as a Park Avenue swell’s, head to the Campbell Apartment atop the West Staircase. Formerly the private office of Jazz Age financier, John W. Campbell, it’s now a glamorous venue for blowing $20 on a martini.

(Hot tip — that same $20 can fetch you sixteen Long Island Blue Points during Happy Hour at the Oyster Bar.)

As for the East Staircase, nearly 100 years younger than its seeming fraternal twin across the Concourse’s marble expanse, that one leads to an Apple Store.

Browse various options for Grand Central Terminal guided and self-guided tours here.

Related Content

Architect Breaks Down Five of the Most Iconic New York City Apartments

A Whirlwind Architectural Tour of the New York Public Library–“Hidden Details” and All

An Architect Demystifies the Art Deco Design of the Iconic Chrysler Building (1930)

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.