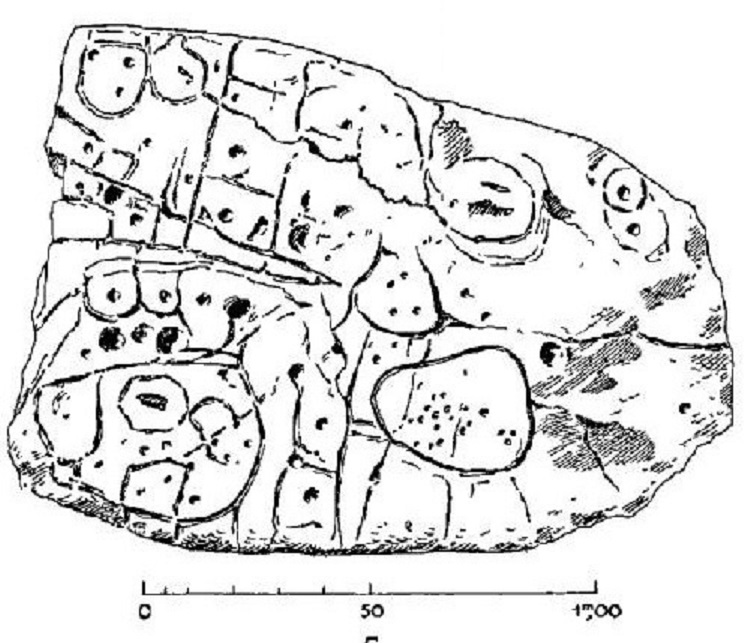

Image by Paul du Châtellier, via Wikimedia Commons

In 1900, the French prehistorian Paul du Châtellier dug up from a burial ground a fairly sizable stone, broken but covered with engraved markings. Even after he put it back together, neither he nor anyone else could work out what the markings represented. “Some see a human form, others an animal one,” he wrote in a report. “Let’s not let our imagination get the better of us and let us wait for a Champollion to tell us what it says.” Champollion, as Big Think’s Frank Jacobs explains, was “the Egyptologist who in 1822 deciphered the hieroglyphics” — which he did with the aid of a more famous inscription-bearing piece of rock, the Rosetta Stone.

Still, the Saint-Bélec slab, as Châtellier’s discovery is now known, has attained a great deal of recognition in the more than 120 years since he unearthed it. But it did so relatively recently, after a long period of relative obscurity.

“In 1994, researchers revisiting du Châtellier’s original drawing found that the intricate markings on the stone looked a lot like a map,” writes Jacobs. “The stone itself, however, had gone missing.” Only in 2014 was it rediscovered in a cellar below the moat of the chateau in Saint-Germain-en-Laye once owned by du Châtellier, by which time it could be subjected to the kind of high-tech analysis unimagined in his lifetime.

Operating on the theory that the artifact was indeed created as a map, France’s INRAP (the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research) “found that the markings on the slab corresponded to the landscape of the Odet Valley” in modern-day Brittany. Then, “using geolocation technology, the researchers established that the territory represented on the slab bears an 80 percent accurate resemblance to an area around a 29-km (18-mi) stretch of the Odet river,” which seems to have been a small kingdom or principality back in the early Bronze Age, between 2150 BC and 1600 BC. This makes the Saint-Bélec slab Europe’s oldest map, and quite possibly the earliest map of any known territory — and certainly the earliest known map of a popular kayaking destination.

Drawing by Paul du Chatellier, via Wikimedia Commons

via Big Think

Related content:

Explore the Hereford Mappa Mundi, the Largest Medieval Map Still in Existence (Circa 1300)

Bronze Age Britons Turned Bones of Dead Relatives into Musical Instruments & Ornaments

What the Rosetta Stone Actually Says

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.