If you attended a seder this month, you no doubt read aloud from the Haggadah, a Passover tradition in which everyone at the table takes turns recounting the story of Exodus.

There’s no definitive edition of the Haggadah. Every Passover host is free to choose the version of the familiar story they like best, to cut and paste from various retellings, or even take a crack at writing their own.

As David Zvi Kalman, publisher of the annual, illustrated Asufa Haggadah told the New York Times, “The Haggadah in America is like Kit Kats in Japan. It’s a product that accepts a wide variety of flavors. It’s probably the most accessible Jewish book on the market.”

21st century adaptations have included Marvelous Mrs. Maisel, Seinfeld, Harry Potter, and Curb Your Enthusiasm themed Haggadot.

There are Haggadot tailored toward feminists, Libertarians, interfaith families, and advocates of the Black Lives Matter movement.

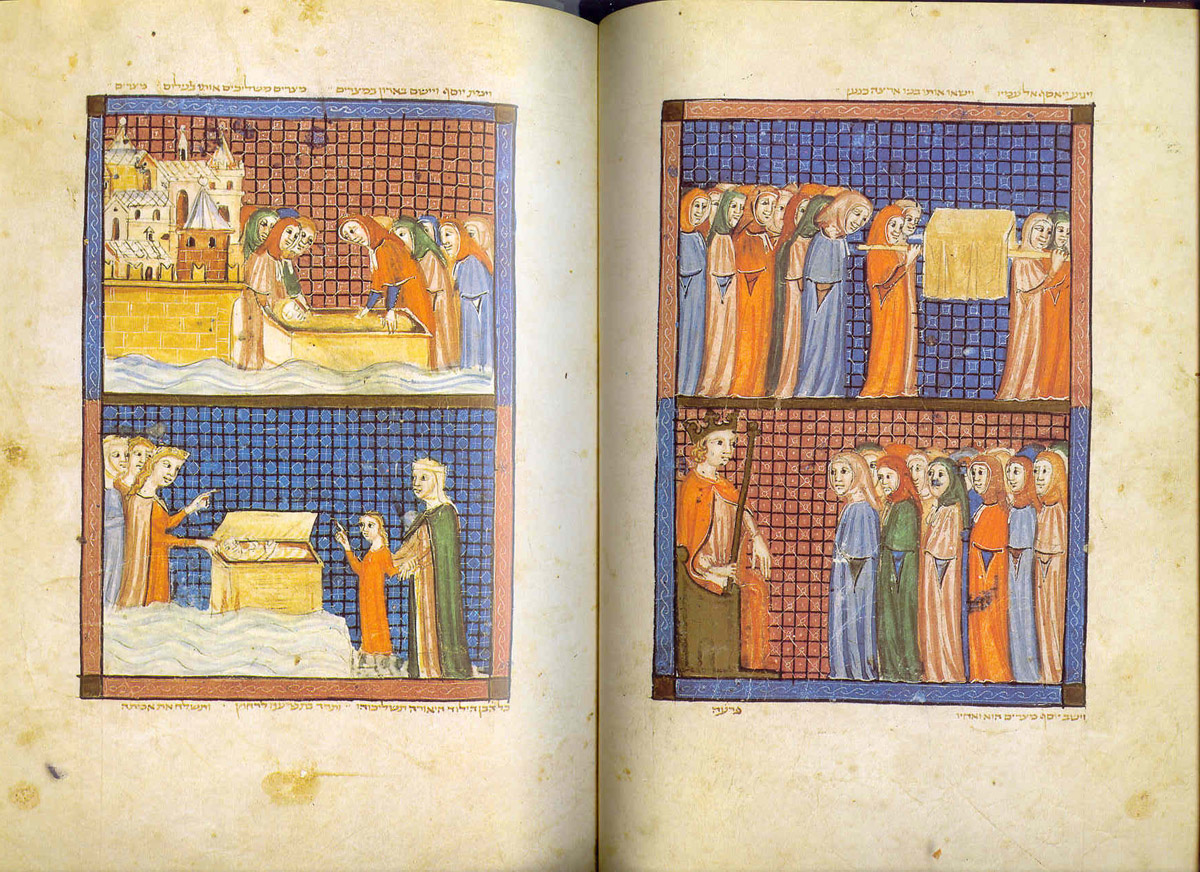

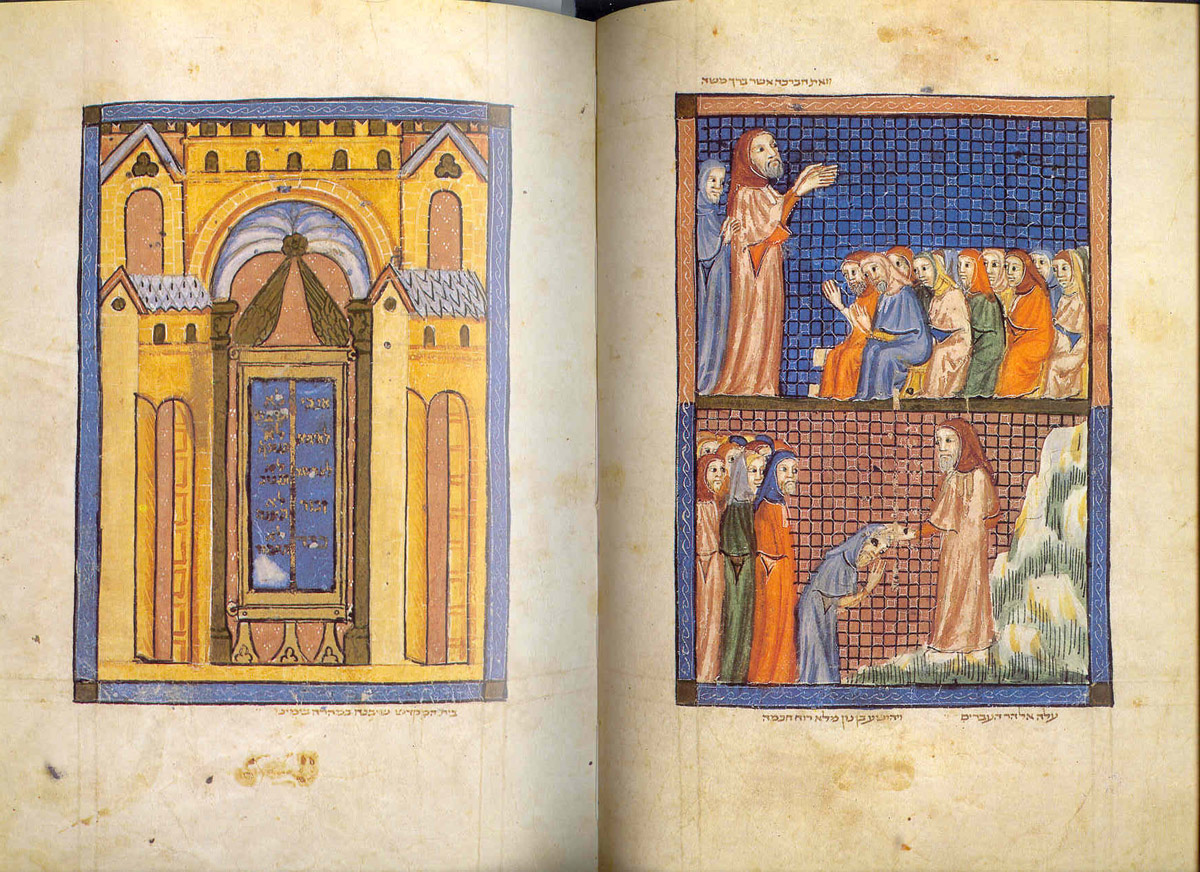

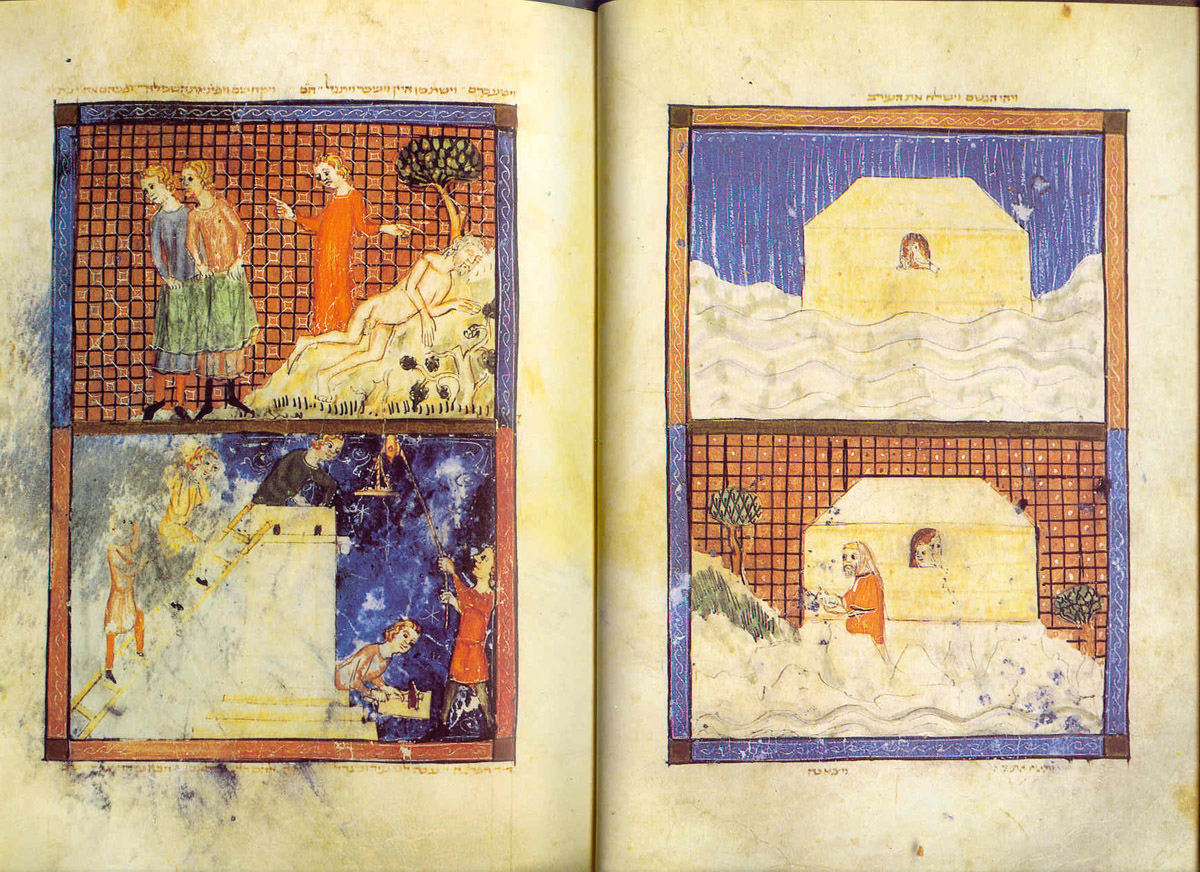

One of the oldest is the miraculously-preserved Sarajevo Haggadah, an illuminated manuscript created by anonymous artists and scribes in Barcelona around 1350.

Though it bears the coats of arms of two prominent families, its provenance is not definitively known.

Leora Bromberg of the University of Toronto’s Thomas Fisher Rare Book Library notes that it is “especially striking for its colorful illuminations of biblical and Passover ritual scenes and its beautifully hand-scribed Sephardic letterforms:”

As precious as this Haggadah was, and still is, Haggadot are books that are meant to be used in festive and messy settings—sharing the table with food, wine, family and guests. The Sarajevo Haggadah was no exception to this; its pages show evidence that it was well used, with doodles, food and red wine stains marking its pages.

Some brave soul took care to smuggle this essential volume out with them when 1492’s Alhambra Decree expelled all Jews from Spain.

The manuscript’s travels thereafter are shrouded in mystery.

It survived the Roman Inquisition by virtue of its contents. As per a 1609 note jotted on one of its pages, nothing therein seemed to be aimed against the Church.

More handwritten notes place the book in the north of Italy in the 16th and 17th centuries, though its new owner is not mentioned by name.

Eventually, it found its way to the hands of a man named Joseph Kohen who sold it to the National Museum of Sarajevo in 1894.

It was briefly sent to Vienna, where a government official replaced its original medieval binding with cardboard covers, chopping its 142 bleached calfskin vellum down to 6.5” x 9” in order to fit them.

It had a narrow escape in 1942, when a high-ranking Nazi official, Johann Fortner, visited the museum, intent on confiscating the priceless manuscript.

The chief librarian, Dervis Korkut, a Muslim, secreted the Haggadah inside his clothing, reputedly telling Fortner that museum staff had turned it over to another German officer.

After that folklore takes over. Korkut either stowed it under the floorboards of his home, buried it under a tree, gave it to an imam in a remote village for safekeeping, or hid it on a shelf in the museum’s library.

Whatever the case, it reappeared in the museum, safe and sound, in 1945.

The museum was ransacked during 1992’s Siege of Sarajevo, but the thieves, ignorant of the Haggadah’s worth, left it on the floor. It was removed to an underground bank vault, where it survived untouched, even as the museum sustained heavy artillery damage.

The president of Bosnia presented it to Jewish community leaders during a Seder three years later.

Shortly thereafter, the head of Sarajevo’s Jewish Community sought the United Nations’ support to restore the Haggadah, and house it in a suitably secure, climate-controlled setting.

A number of facsimiles have been created, and the original codex once again resides in the museum where it is stored under the prescribed conditions, and displayed on rare special occasions, as “physical proof of the openness of a society in which fear of the Other has never been an incurable disease.”

UNESCO added it to its Memory of the World Register in 2017, “praising the courage of the people who, even in the darkest of times during World War II, appreciated its importance to Jewish Heritage, as well as its embodiment of diversity and intercultural harmony depicted in its illustration:”

Regardless of their own religious beliefs, they risked their lives and did all in their power to safeguard the Haggadah for future generations. Its destruction would be a loss for humanity. Protecting it is a symbol of the values which we hold dear.

For those interested, the Sarajevo Haggadah figures centrally in the bestselling 2008 novel People of the Book, written by the Pulitzer Prize-winning author Geraldine Brooks. You can read an New Times review here.

Related Content

Turning the Pages of an Illuminated Medieval Manuscript: An ASMR Museum Experience

The Medieval Masterpiece, the Book of Kells, Has Been Digitized and Put Online

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.