The earliest known works of Japanese art date from the Jōmon period, which lasted from 10,500 to 300 BC. In fact, the period’s very name comes from the patterns its potters created by pressing twisted cords into clay, resulting in a predecessor of the “wave patterns” that have been much used since. In the Heian period, which began in 794, a new aristocratic class arose, and with it a new form of art: Yamato‑e, an elegant painting style dedicated to the depiction of Japanese landscapes, poetry, history, and mythology, usually on folding screens or scrolls (the best known of which illustrates The Tale of Genji, known as the first novel ever written).

This is the beginning of the story of Japanese art as told in the half-hour-long Behind the Masterpiece video above. It continues in 1185 with the Kamakura period, whose brewing sociopolitical turmoil intensified in the subsequent Nanbokucho period, which began in 1333. As life in Japan became more chaotic, Buddhism gained popularity, and along with that Indian religion spread a shift in preferences toward more vital, realistic art, including celebrations of rigorous samurai virtues and depictions of Buddhas. In this time arose the form of sumi‑e, literally “ink picture,” whose tranquil monochromatic minimalism stands in the minds of many still today for Japanese art itself.

Japan’s long history of fractiousness came to an end in 1568, when the feudal lord Oda Nobunaga made decisive moves that would result in the unification of the country. This began the Azuchi-Momoyama period, named for the castles occupied by Nobunaga and his successor Toyotomi Hideyoshi. The castle walls were lavishly decorated with large-scale paintings that would define the Kanō school. Traditional Japan itself came to an end in the long, and military-governed Edo period, which lasted from 1615 to 1868. The stability and prosperity of that era gave rise to the best-known of all classical Japanese art forms: kabuki theatre, haiku poetry, and ukiyo‑e woodblock prints.

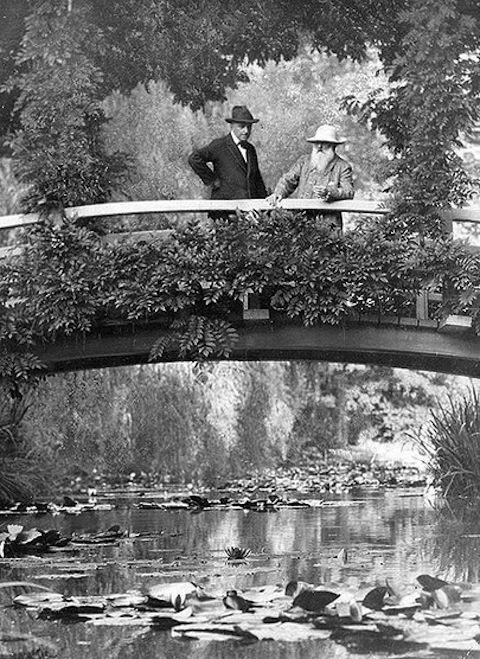

With their large market of merchant-class buyers, ukiyo‑e artists had to be prolific. Many of their works survive still today, the most recognizable being those of masters like Utamaro, Hokusai, and Hiroshige. Here on Open Culture, we’ve previously featured Hokusai’s series Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji as well as its famous installment The Great Wave Off Kanagawa. As Japan opened up to the west from the middle of the nineteenth century, the various styles of ukiyo‑e became prime ingredients of the Japonisme trend, which extended the influence of Japanese art to the work of major Western artists like Degas, Manet, Monet, van Gogh, and Toulouse-Lautrec.

The Meiji Restoration of 1868 opened the long-isolated Japan to world trade, re-established imperial rule, and also, for historical purposes, marked the country’s entry into modernity. This inspired an explosion of new artistic techniques and movements including Yōga, whose participants rendered Japanese subject matter with European techniques and materials. Born early in the Shōwa era but still active in her nineties, Yayoi Kusama now stands (and in Paris, at enormous scale in statue form) as the most prominent Japanese artist in the world. The rich psychedelia of her work belongs obviously to no single culture or tradition — but then again, could an artist of any other country have come up with it?

Related content:

How to Paint Like Yayoi Kusama, the Avant-Garde Japanese Artist

The Entire History of Japan in 9 Quirky Minutes

The History of Western Art in 23 Minutes: From the Prehistoric to the Contemporary

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.