Shoes and boots, show where your feet have gone. —Guy Sebeus, 10 New Scythian Tales

In the age of fast fashion, when planned obsolescence, cheap materials, and shoddy construction have become the norm, how startling to encounter a stylish women’s boot that’s truly built to last…

…like, for 2300 years.

It helps to have landed in a Scythian burial mound in Siberia’s Altai Mountains, where the above boot was discovered along with a number of nomadic afterlife essentials—jewelry, food, weapons, and clothing.

These artifacts (and their mummified owners) were well preserved thanks to permafrost and the painstaking attention the Scythians paid to their dead.

As curators at the British Museum wrote in advance of the 2017 exhibition Scythians: Warriors of Ancient Siberia:

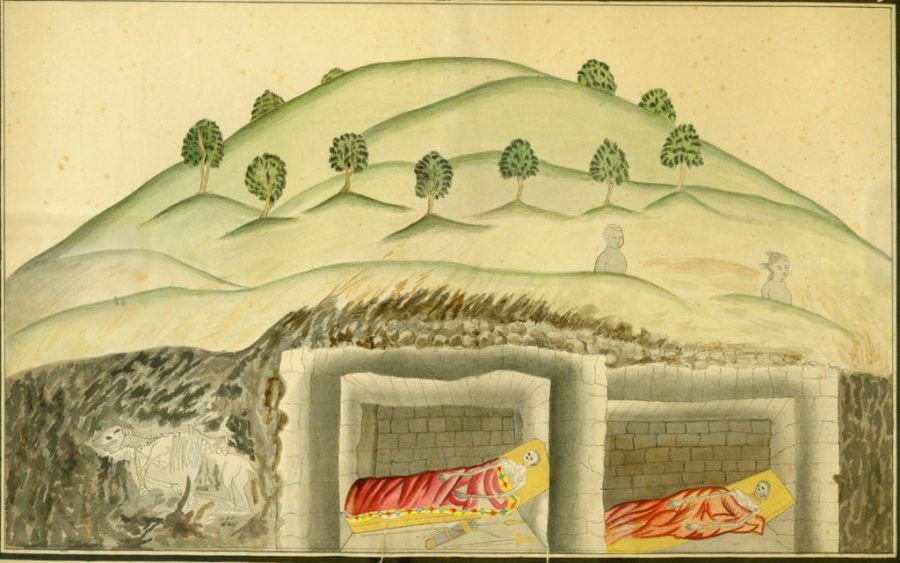

Nomads do not leave many traces, but when the Scythians buried their dead they took care to equip the corpse with the essentials they thought they needed for the perpetual rides of the afterlife. They usually dug a deep hole and built a wooden structure at the bottom. For important people these resembled log cabins that were lined and floored with dark felt – the roofs were covered with layers of larch, birch bark and moss. Within the tomb chamber, the body was placed in a log trunk coffin, accompanied by some of their prized possessions and other objects. Outside the tomb chamber but still inside the grave shaft, they placed slaughtered horses, facing east.

18th-century watercolor illustration of a Scythian burial mound. Archive of the Institute of Archaeology of the Russian Academy of Sciences, St Petersburg

The red cloth-wrapped leather bootie, now part of the State Hermitage Museum’s collection, is a stunner, trimmed in tin, pyrite crystals, gold foil and glass beads secured with sinew. Fanciful shapes—ducklings, maybe?—decorate the seams. But the true mindblower is the remarkable condition of its sole.

Speculation is rampant on Reddit, as to this bottom layer’s pristine condition:

Maybe the boot belonged to a high-ranking woman who wouldn’t have walked much…

Or Scythians spent so much time on horseback, their shoe leather was spared…

Or perhaps it’s a high quality funeral garment, reserved for exclusively post-mortem use…

The British Museum curators’ explanation is that Scythians seated themselves on the ground around a communal fire, subjecting their soles to their neighbors’ scrutiny.

Become better acquainted with Scythian boots by making a pair, as ancient Persian empire reenactor Dan D’Silva did, documenting the process in a 3‑part series on his blog. How you bedazzle the soles is up to you.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2020.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Stylish 2,000-Year-Old Roman Shoe Found in a Well

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.