In the neverending quest to elevate themselves above the fray, today’s mixologists — formerly known as bartenders — are putting a modern spin on obscure cocktail recipes, and resurrecting anachronistic spirits like mahia, Chartreuse, Usquebaugh, and absinthe.

Might we see a return of Vin Mariani, a Belle Époque ‘tonic wine’ that was hit with such august personages as Queen Victoria, Ulysses S. Grant, Alexander Dumas and Emile Zola?

Probably not.

It’s got coca in it, known for its psychoactive alkaloid, cocaine.

Corsican chemist Angelo Mariani came up with the restorative beverage, formally known as Vin Tonique Mariani à la Coca de Peroum, in 1863, inspired by physician and anthropologist Paolo Mantegazza who served as his own guinea pig after observing native use of coca leaves while on a trip to South America:

I sneered at the poor mortals condemned to live in this valley of tears while I, carried on the wings of two leaves of coca, went flying through the spaces of 77,438 words, each more splendid than the one before…An hour later, I was sufficiently calm to write these words in a steady hand: God is unjust because he made man incapable of sustaining the effect of coca all life long. I would rather have a life span of ten years with coca than one of 10,000,000,000,000,000,000 000 centuries without coca.

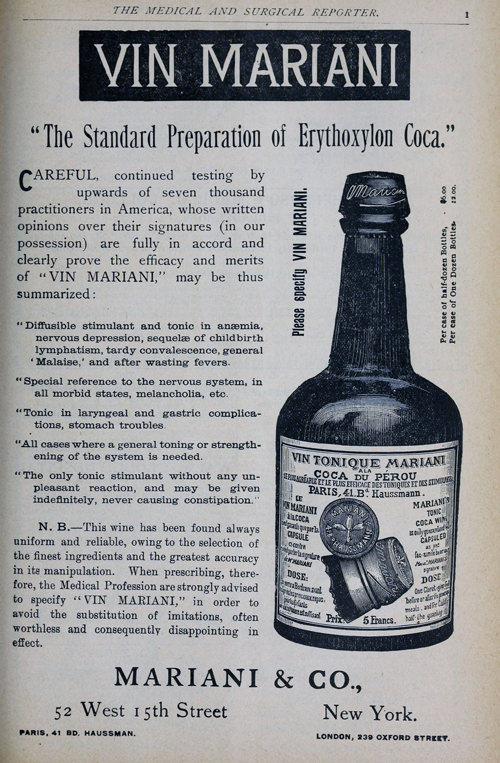

Mariani identified an untapped opportunity and added ground coca leaves to Bordeaux, at a ratio of 6 milligrams of coca to one ounce of wine.

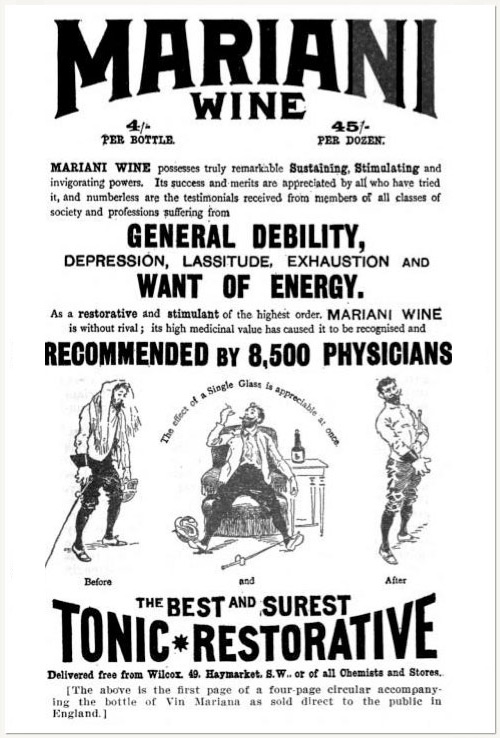

Unsurprisingly, the resulting concoction not only took the edge off, it was accorded a number of healthful benefits in an age where general cure-alls were highly prized.

The recommended dosage for adults was two or three glasses a day, before or after meals. For kids, the amount could be divided in two.

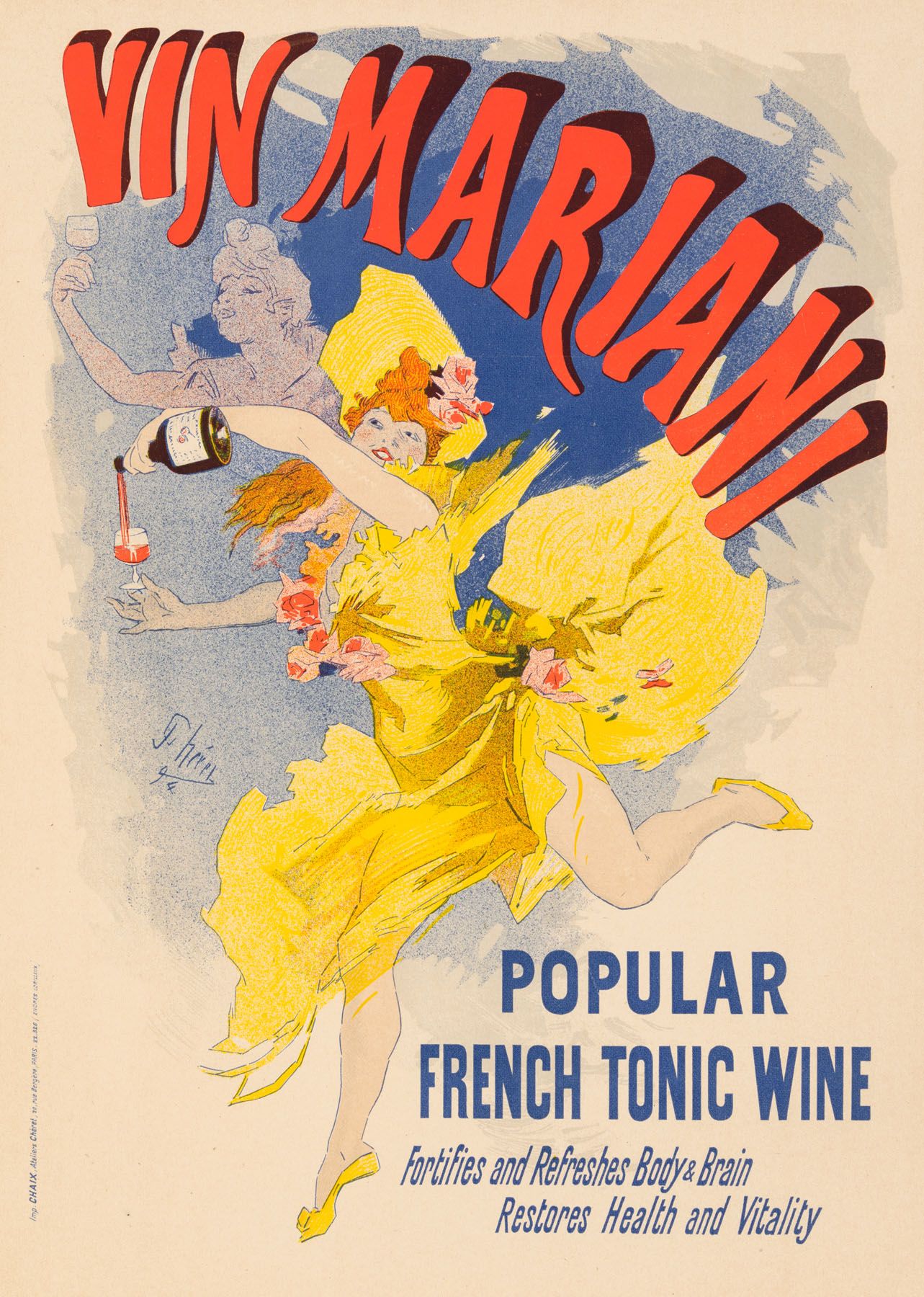

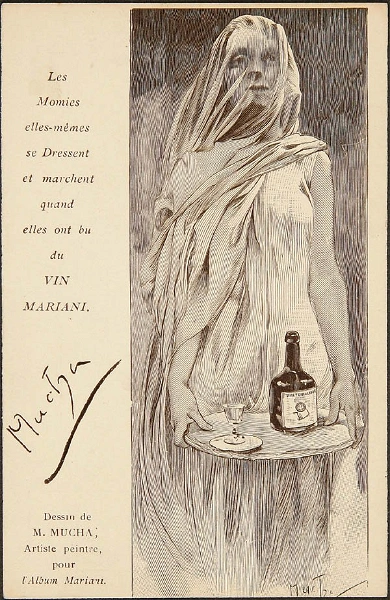

Reigning masters of graphic design were enlisted to promote the miracle elixir.

Jules Chéret leaned into its energy boosting effects by depicting a comely young woman clad in skimpy, sheer yellow replenishing her glass mid-leap, while Alphonse Mucha went dark, claiming that “the mummies themselves stand up and walk after drinking Vin Mariani.”

While we’re on the subject of corpse revivers, 21st-century mixologists will please note that a cocktail of Vin Mariani, vermouth and bitters, served with a twist, was a particularly popular preparation, especially across the Atlantic, where Vin Mariani was exported in a more potent version containing 7.2 milligrams of coca.

Angelo Mariani’s innovations were not limited to the chemistry of alcoholic compounds.

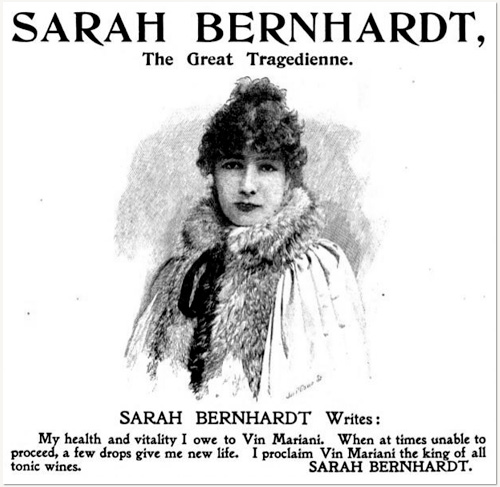

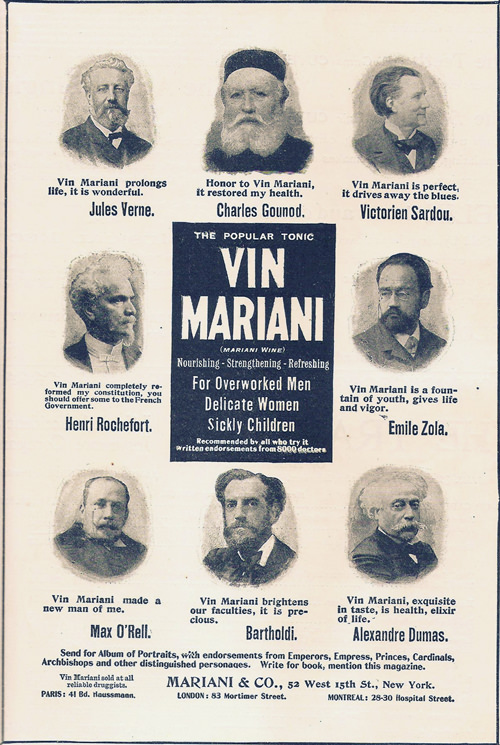

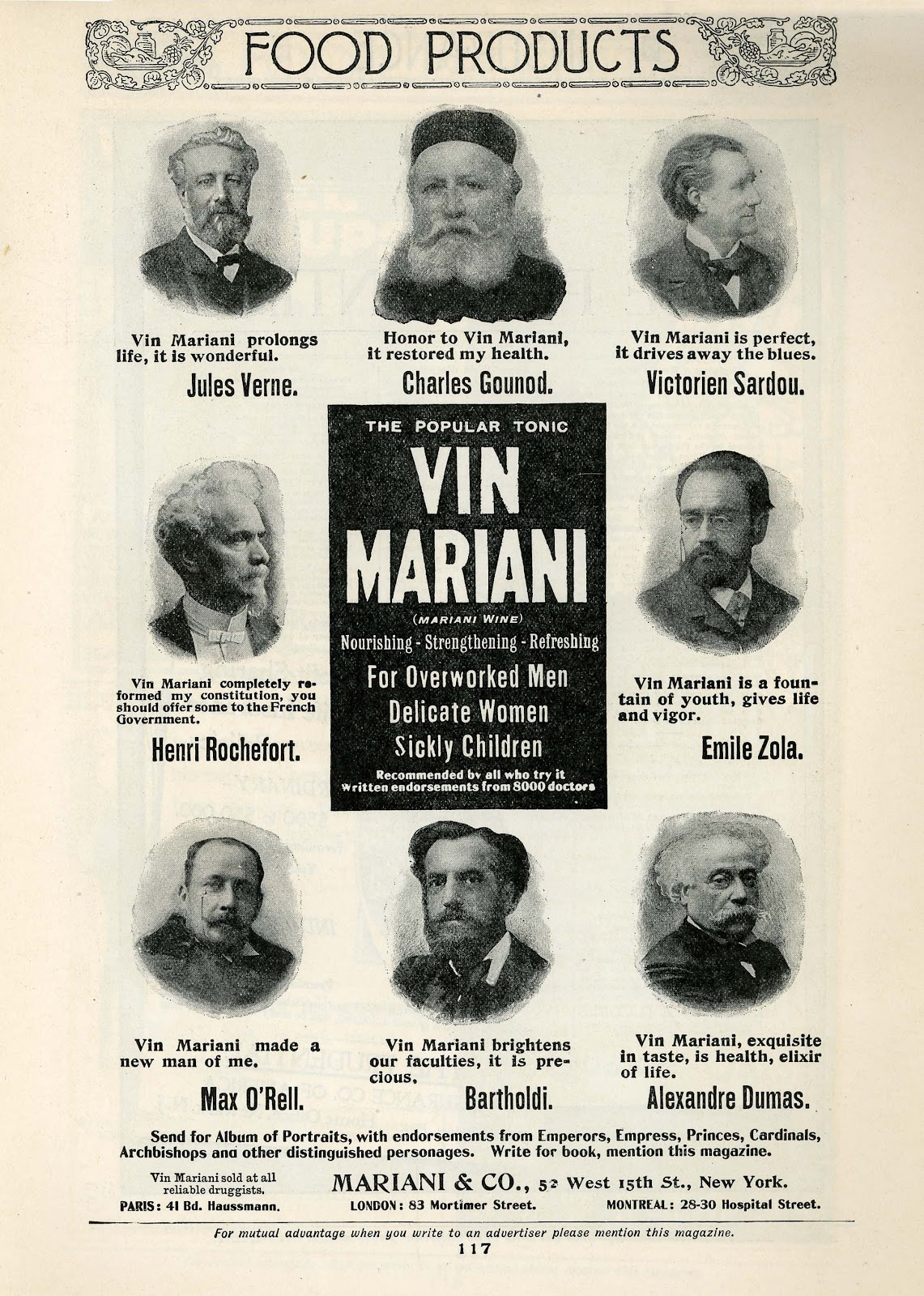

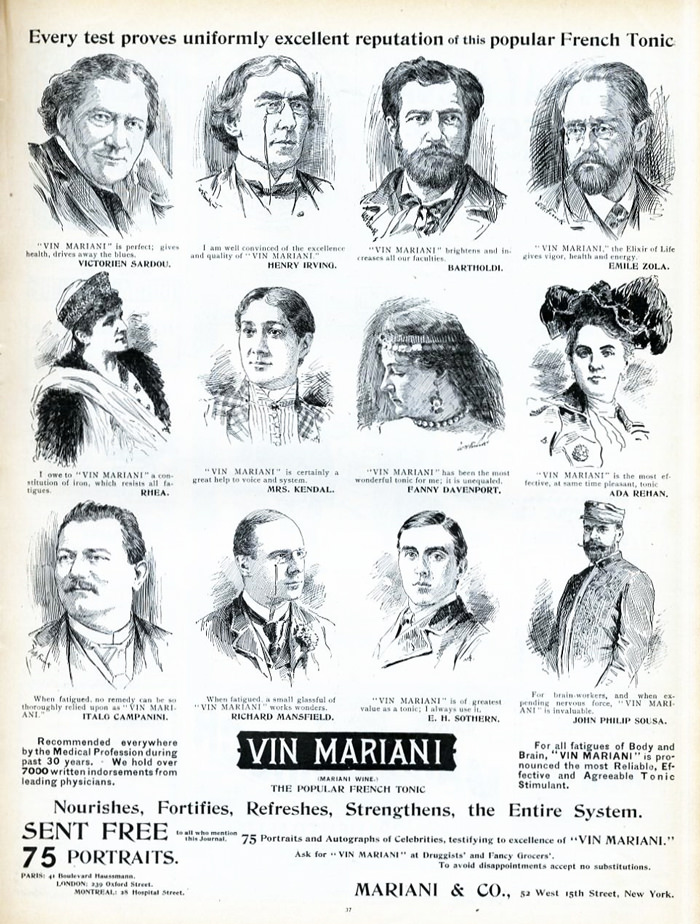

He was also a marketing genius, who curried celebrity favor by sending a complimentary case of Vin Mariani to dozens of famous names, along with a humble request for an endorsement and photo, should the contents prove pleasing.

These accolades were collected and repurposed as advertisements that assured adoring fans and followers of the product’s quality.

Sarah Bernhardt conferred superstar status on the drink, and not so subtly shored up her own, grandly pronouncing the blend the “King of Tonics, Tonic of Kings:”

I have been delighted to find Vin Mariani in all the large cities of the United States, and it has, as always, largely helped to give me that strength so necessary in the performance of the arduous duties which I have imposed upon myself. I never fail to praise its virtues to all my friends and I heartily congratulate upon the success which you so well deserve.

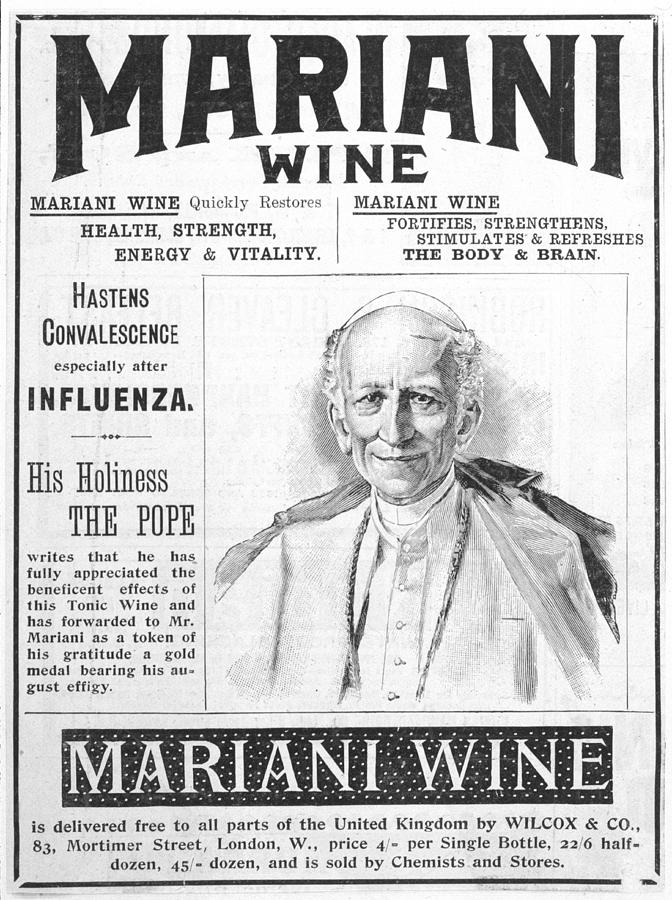

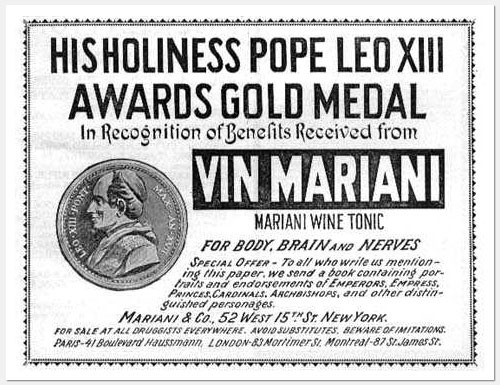

Pope Leo XIII not only carried “a personal hip flask” of the stuff to “fortify himself in those moments when prayer was insufficient,” he invented and awarded a Vatican gold medal to Vin Mariani “in recognition of benefits received.”

Mariani eventually packaged the glowing endorsements he’d been squirreling away as Portraits from Album Mariani. It’s a compendium of famous artists, writers, actors, and musicians of the day, some remembered, mostly not…

Composer John Philip Sousa:

When worn out after a long rehearsal or a performance, I find nothing so helpful as a glass of Vin Mariani. To brain workers and those who expend a great deal of nervous force, it is invaluable.

Opera singer Lillian Blauvelt:

Vin Mariani is the greatest of all tonic stimulants for the voice and system. During my professional career, I have never been without it.

Illustrator Albert Robida:

At last! At last! It has been discovered — they hold it, that celebrated microbe so long sought after — the microbe of microbes that kills all other microbes. It is the great, the wonderful, the incomparable microbe of health! It is, it is Vin Mariani!

(We suspect Robida penned his entry after swallowing more than a few glasses… or he was of a mischievous nature and would’ve fit right in with the Surrealists, the Futurists, Fluxus, or any other movement that jabbed at the bourgeoisie with hyperbole and humor.

Mariani used the album to publish the Philadelphia Medical Times’ defense of celebrity endorsements:

The array of notable names is a strong one. Too strong in standing, as well as in numbers, to allow of the charge of interested motives.

Mariani also included an excerpt from the New York Medical Journal, denouncing the unscrupulous manufacturers of “rival preparations of coca” who pirated Vin Mariani’s glowing reviews, “craftily making those records appear to apply to their own preparations.”

Elsewhere in the album, medical authorities tout Vin Mariani’s success in combatting such maladies as headaches, heart strain, brain exhaustion, spasms, la grippe, laryngeal afflictions, influenza, inordinate irritability and worry.

They fail to mention that it could get you much higher than vins ordinaires, defined, for purposes of this post, as “wines lacking in coca.”

The psychoactive properties of coca definitely received a boost from the alcohol, a collision that gave rise to a third chemical compound, cocaethylene, a long-lasting intoxicant that produces intense euphoria, along with a heightened risk of cardiotoxicity and sudden death.

…some dead celebrities could likely tell us a thing or two about it.

Mariani’s fortunes began to turn early in the 20th century, owing to the Pure Food and Drug Act, the growing temperance movement, and increased public awareness of the dangers of cocaine.

We may never see a Vin Mariani cocktail on the menu at Death & Co, Licorería Limantour, or Paradiso, but the Drug Enforcement Administration’s Museum keeps a bottle on hand.

Related Content

How a Young Sigmund Freud Researched & Got Addicted to Cocaine, the New “Miracle Drug,” in 1894

The Coffee Pot That Fueled Honoré de Balzac’s Coffee Addiction

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.