Images on this page come courtesy of the Musei del Bargello

In the year 1530, Michelangelo was sentenced to death by Pope Clement VII — who, not coincidentally, was born Giulio de’ Medici. That famous dynasty, which once seemed to hold absolute economic and political power in Florence, had just seen off a violent challenge to its rule by republican-minded Florentines who, emboldened by the sack of Rome in 1527, took their city from the House of Medici that same year. Alas, that particular Republic of Florence proved short-lived, thanks to the pope and Emperor Charles V’s agreement agreed to use military power to return it to Medici hands.

During the struggles against the Medici, the Florence-born Michelangelo had come to the aid of his hometown by working on its fortifications. It seems to have been his participation in the revolt that drew the ire of the Medici, despite their court’s on-and-off patronage of his work for the preceding four decades.

Mercifully, they never actually executed Michelangelo, and indeed pardoned him before long–not least so he could finish his work on the Sistine Chapel and the Medici family tomb. But how did he occupy himself while still living under the death sentence?

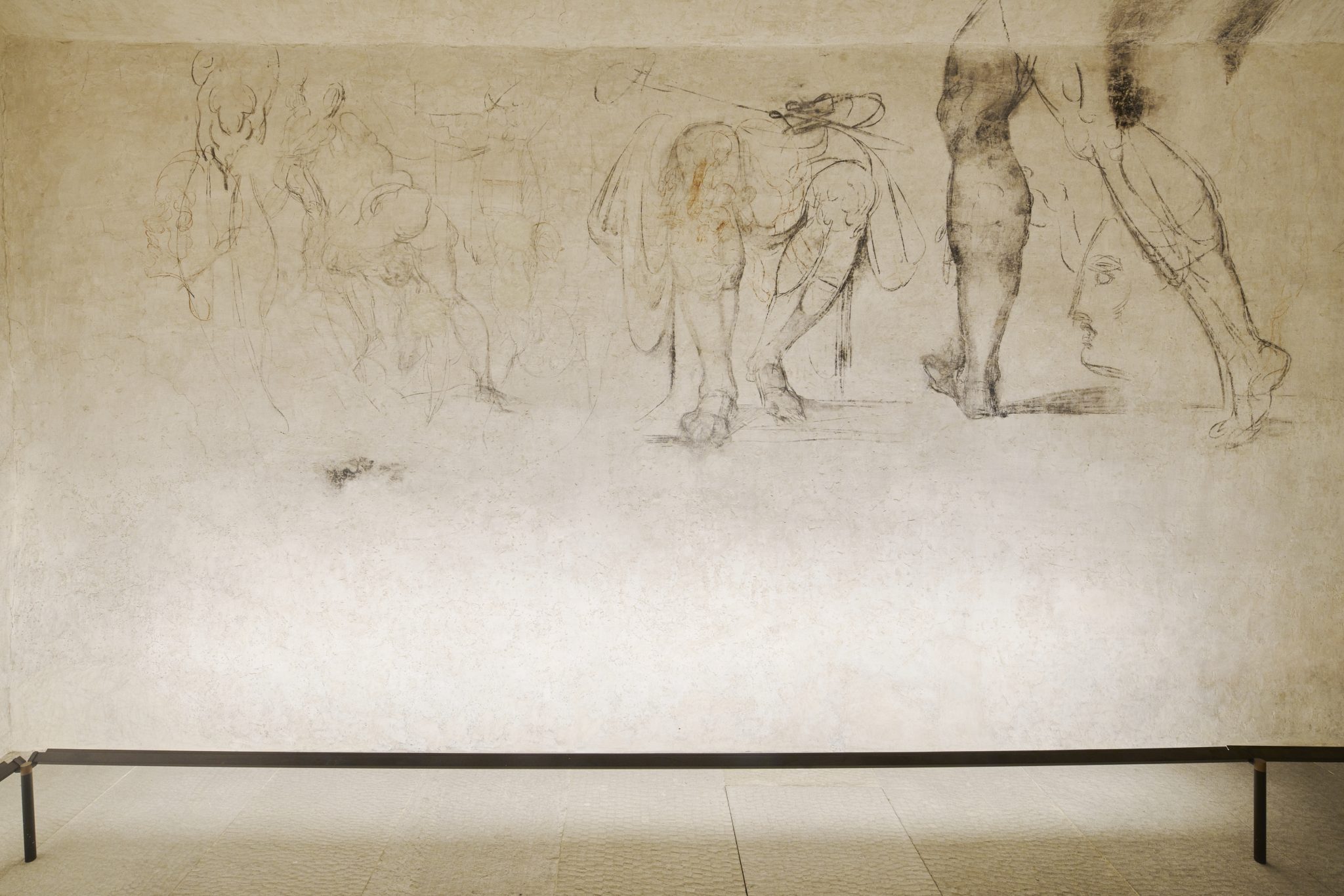

As one theory has it, he simply hid out — and in a corner of what’s now the Medici Chapels Museum at that. In a “tiny chamber beneath the Medici Chapels in the Basilica of San Lorenzo in 1530,” writes the Guardian’s Angela Giuffrida, Michelangelo spent a couple months “making dozens of drawings that are reminiscent of his previous works, including a drawing of Leda and the Swan, a painting produced during the same year that was later lost.” All of these he drew directly on the walls, and their existence “remained unknown until 1975 when Paolo Dal Poggetto, then the director of the Medici Chapels, one of five museums that make up the Bargello Museums, was searching for a suitable space to create a new exit for the museum.”

“Others doubt that Michelangelo, already in his 50s and an acclaimed artist with powerful patrons, would have spent time in such a dingy hide out,” writes the New York Times’ Jason Horowitz. “But many scholars believe that the sketches show his hand”: the “imposing nude near the entrance” that evokes The Resurrection of Christ; the sketches that “resemble the central figure of his The Fall of Phaeton. Some even think a flexed and disembodied arm on the wall evokes his David statue.” And starting next week, visitors will be able to judge these very drawings for themselves.

Not that you can just waltz into this stanza segreta: “Visits will be kept to groups of four and limited to 15 minutes, with 45 minute lights-out periods in between to protect the drawings,” Horowitz writes. ‘Tickets, each connected to a specific person whose I.D. will be checked to prevent tour operators from gobbling them up, will cost 32 euros (about $34), and include access to the Medici tombs.” During your own fifteen minutes in this cramped, obscure room turned tastefully-lit gallery, you may or may not feel the presence of Michelangelo, but you’ll surely find yourself reminded that a true artist never stops creating, no matter the circumstances in which he finds himself.

Related Content:

Watch the Painstaking and Nerve-Racking Process of Restoring a Drawing by Michelangelo

Michelangelo’s David: The Fascinating Story Behind the Renaissance Marble Creation

New Video Shows What May Be Michelangelo’s Lost & Now Found Bronze Sculptures

Michelangelo’s Illustrated Grocery List

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.