What history nerd doesn’t thrill to Thomas Edison speaking to us from beyond the grave in a 50th anniversary repeat of his groundbreaking 1877 spoken word recording of (those hoping for loftier stuff should dial it down now) Mary Had a Little Lamb?

The original represents the first time a recorded human voice was successfully captured and played back. We live in hope that the fragile tinfoil sheet on which it was recorded will turn up in someone’s attic someday.

Apparently Edison got it in the can on the first take. The great inventor later reminisced that he “was never so taken aback” in his life as when he first heard his own voice, issuing forth from the phonograph into which he’d so recently shouted the famous nursery rhyme:

Everybody was astonished. I was always afraid of things that worked the first time.

His achievement was a game changer, obviously, but it wasn’t the first time human speech was successfully recorded, as Kings and Things clarifies in the above video.

That honor goes to Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville, whose phonautograph, patented in 1857, transcribed vocal sounds as wave forms etched onto lampblack-coated paper, wood, or glass.

Edison’s plans for his invention hinged on its ability to reproduce sound in ways that would be familiar and of service to the listening public. A sampling:

- A music player

- A device for creating audiobooks for blind people

- A linguistic tool

- An academic resource of archived lectures

- A record of telephone conversations

- A means of capturing precious family memories.

Léon Scott’s vision for his phonautograph reflects his preoccupation with the science of sound.

A professional typesetter, with an interest in shorthand, he conceived of the phonautograph as an artificial ear capable of reproducing every hiccup and quirk of pronunciation far more faithfully than a stenographer ever could. It was, in the words of audio historian Patrick Feaster, the “ultimate speech-to-text machine.”

As he told NPR’s Talk of the Nation, Léon Scott was driven to “get sounds down on paper where he could look at them and study them:”

…in terms of what we’re talking about here visually, anybody who’s ever used audio editing software should have a pretty good idea of what we’re talking about here, that kind of wavy line that you see on your screen that somehow corresponds to a sound file that you’re working with…He was hoping people would learn to read those squiggles and not just get the words out of them.

Although Léon Scott managed to sell a few phonautographs to scientific laboratories, the general public took little note of his invention. He was pained by the global acclaim that greeted Edison’s phonograph 21 years later, fearing that his own name would be lost to history.

His fear was not unfounded, though as Conan O’Brien, of all people, mused, “eventually, all our graves go unattended.”

But Léon Scott got a second act, as did several unidentified long-dead humans whose voices he had recorded, when Dr. Feaster and his First Sounds colleague David Giovannoni converted some phonautograms to playable digital audio files using non-contact optical-scanning technology from the Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory.

Dr. Feaster describes the eerie experience of listening to the cleaned-up spoken word tracks after a long night of tweaking file speeds, using Léon Scott’s phonautograms of tuning forks as his guide:

I’m a sound recording historian, so hearing a voice from 100 years ago is no real surprise for me. But sitting there, I was just kind of stunned to be thinking, now I’m suddenly at last listening to a performance of vocal music made in France before the American Civil War. That was just a stunning thing, feeling like a ghost is trying to sing to me through that static.

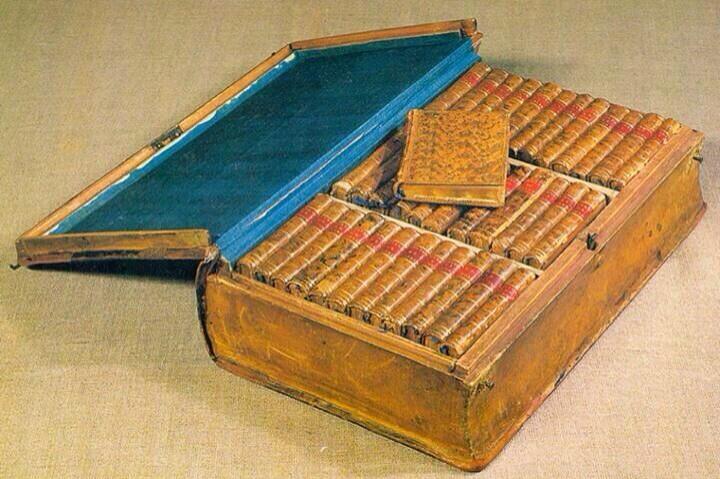

Scanning technology also allowed historians to create playable digital files of fragile foil recordings made on Edison devices, like the St. Louis Tinfoil , made by writer and early adopter Thomas Mason in the summer of 1878, as a way of showing off his new-fangled phonograph, purchased for the whopping sum of $95.

The British Library’s Tinfoil Recording is thought to be the earliest in existence. It features an as-yet unidentified woman, who may or may not be quoting from social theorist Harriet Martineau… this garbled ghost is exceptionally difficult to pin down.

Far easier to decipher are the 1889 recordings of Prussian Field Marshall Helmuth Von Multke, who was born in 1800, the last year of the 18th century, making his the earliest-born recorded voice in audio history.

The nonagenarian recites from Hamlet and Faust, and congratulates Edison on his astonishing invention:

This phonograph makes it possible for a man who has already long rested in the grave once again to raise his voice and greet the present.

Related Content

Suzanne Vega, “The Mother of the MP3,” Records “Tom’s Diner” with the Edison Cylinder

A Beer Bottle Gets Turned Into a 19th Century Edison Cylinder and Plays Fine Music

400,000+ Sound Recordings Made Before 1923 Have Entered the Public Domain

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.