Copyright by Charities Aid Foundation America thanks to the generous support of the Bloch family; restoration and digitization: Jewish Museum Berlin. This pertains to all images on this page.

Perhaps at some point in the future,

the poems in your tongue I composed,

will be brought to your notice,

and if so, to delight will I then be disposed.

— Curt Bloch, Het Onderwater Cabaret

Zines typically tend toward the ephemeral, owing to their small circulations, erratic publication schedules, and the unpredictable lives of their creators.

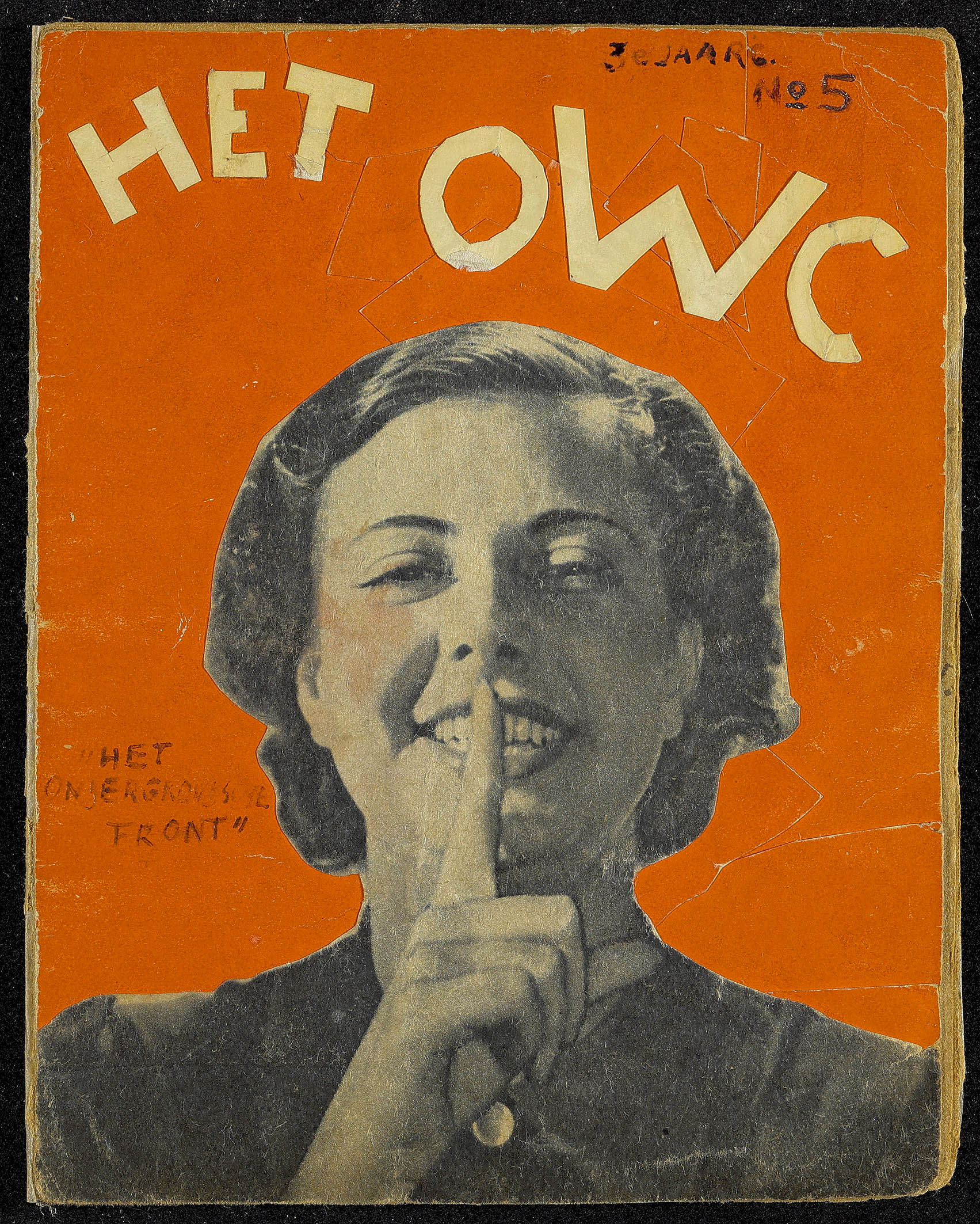

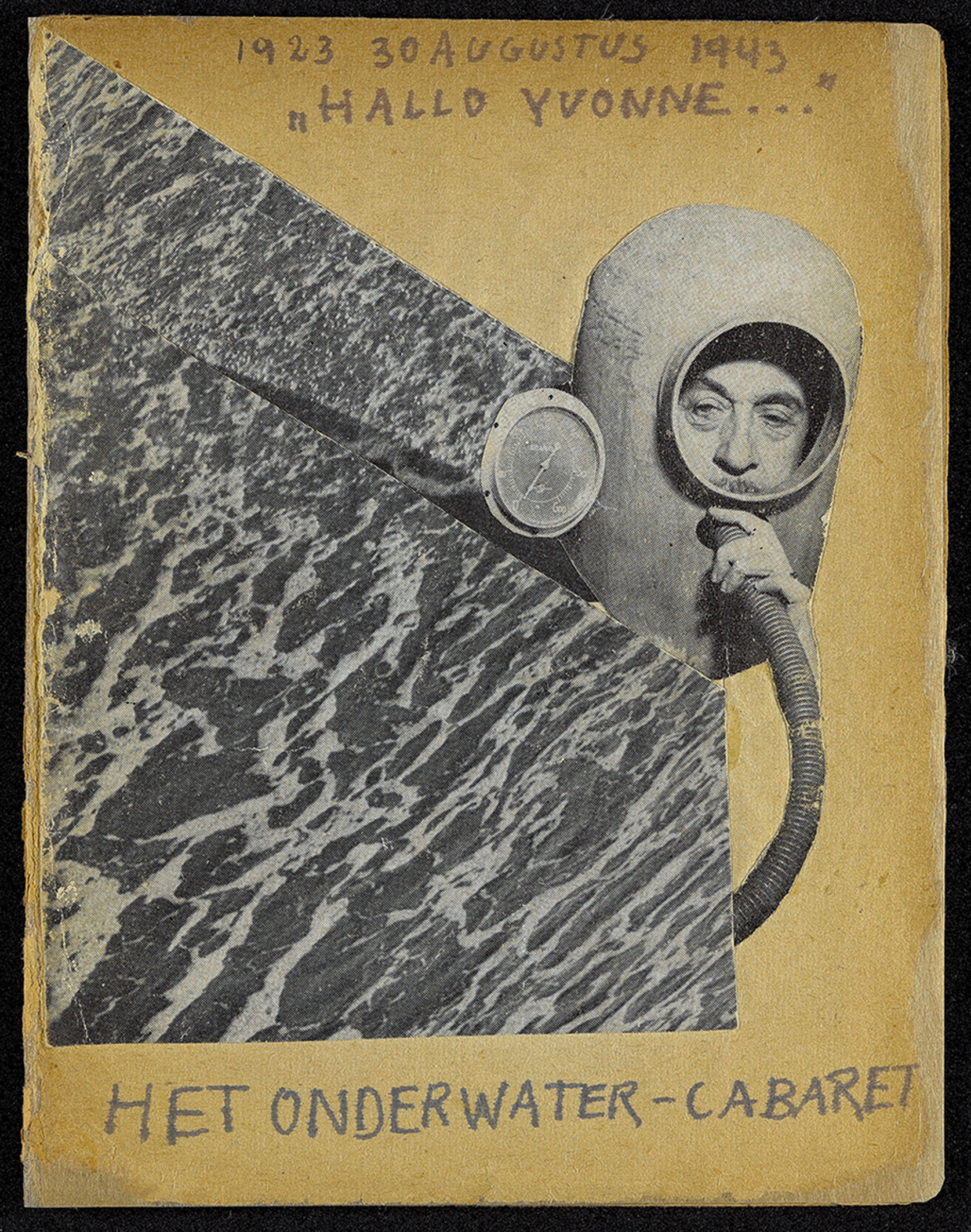

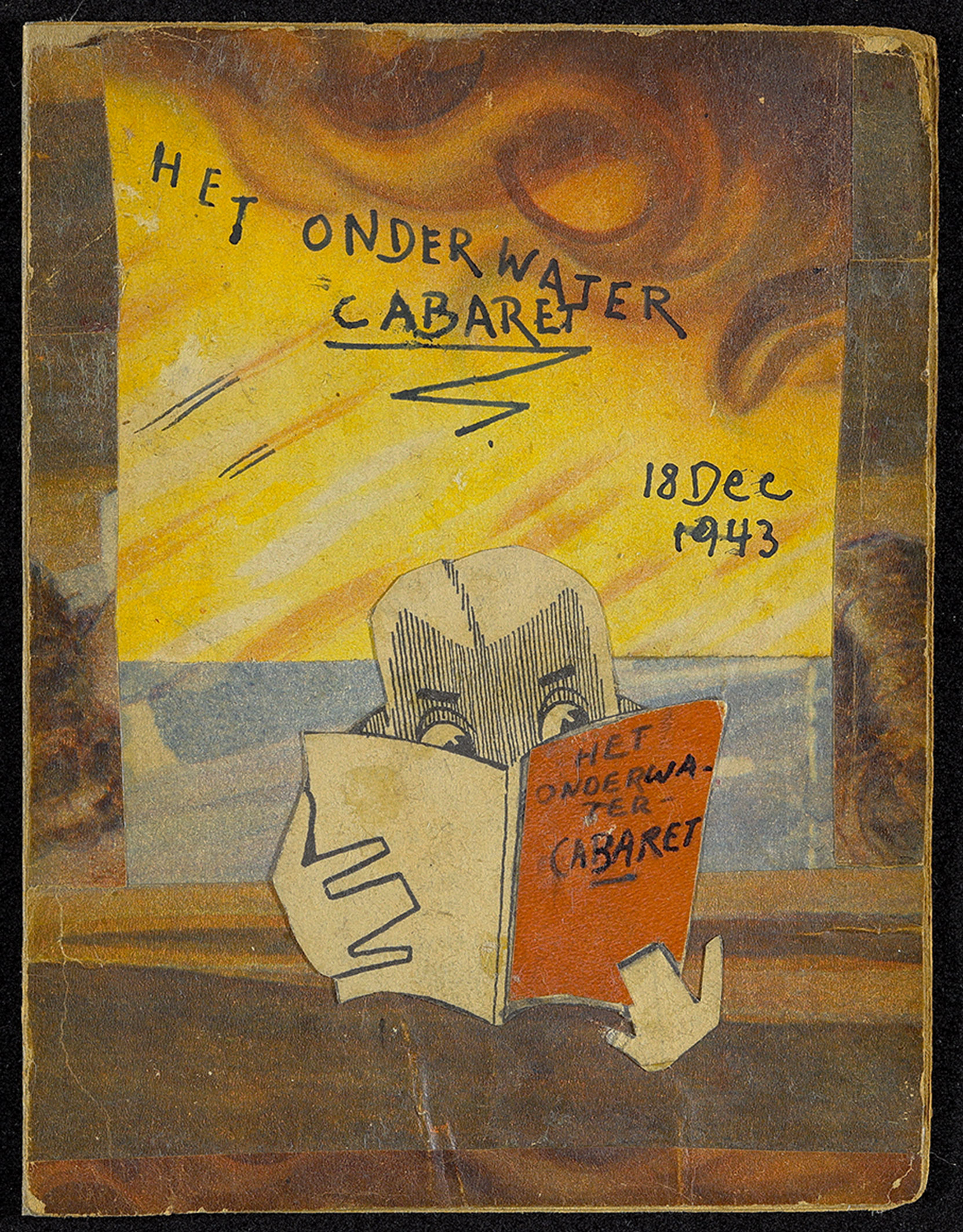

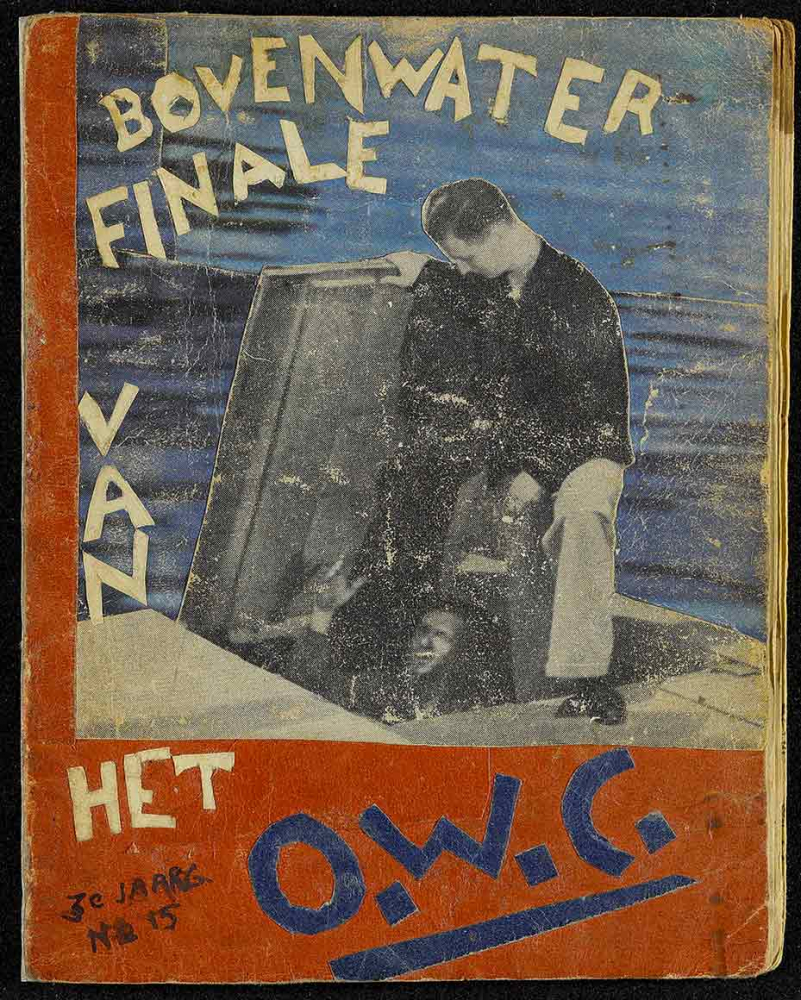

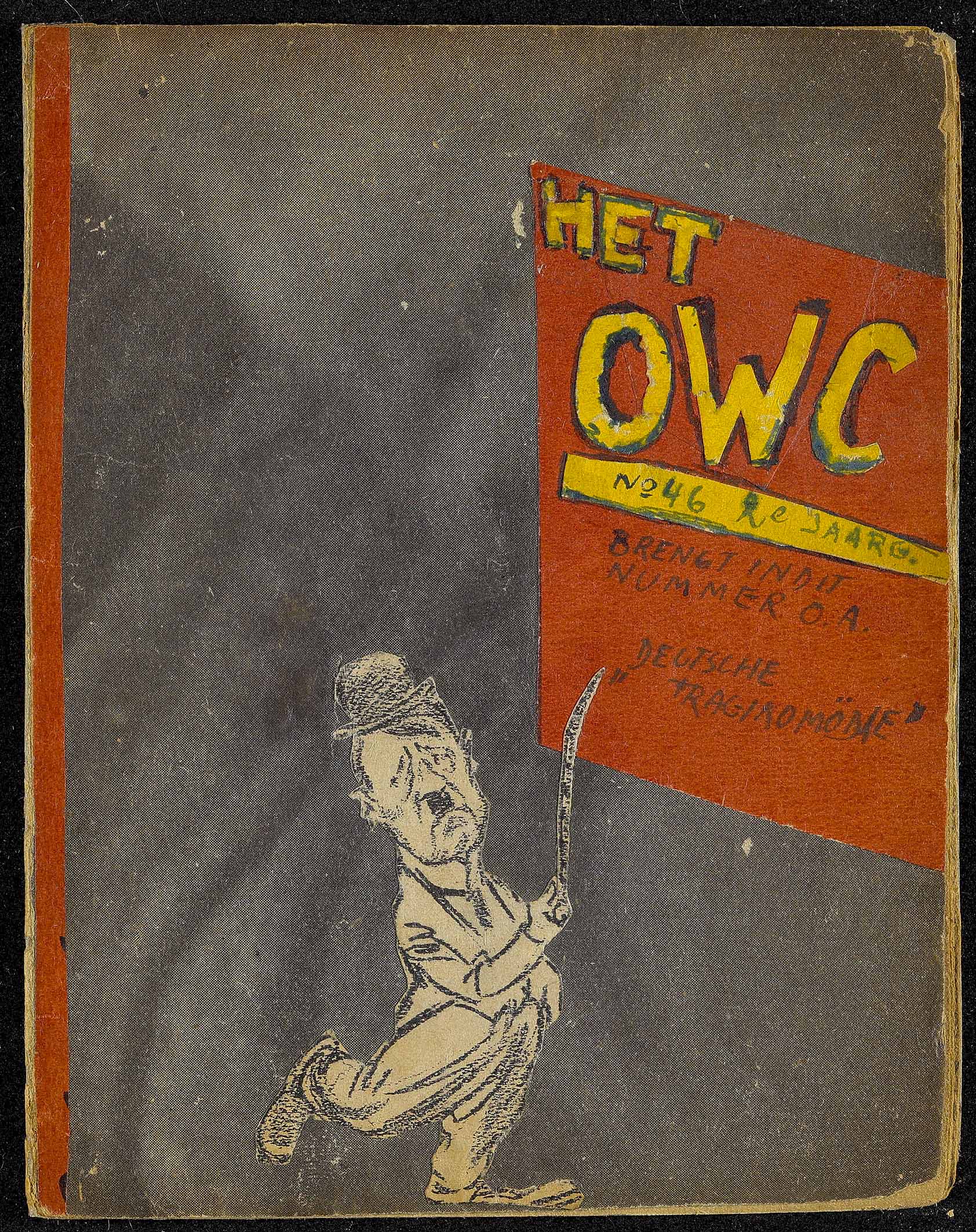

Curt Bloch’s zine, Het Onderwater Cabaret (The Underwater Cabaret) defies these odds.

Bloch not only produced an impressive 95 issues between August 1943 and April 1945, he did so as a German Jew hiding from the Nazis in the rafters of a private home in the Dutch city of Enschede, not far from the German border.

His cut-and-paste illustrations are part of a long-standing zine continuum, made possible in part by helpers who furnished him with pens, glue, newspapers and other collage-worthy materials, in addition to food and other necessities.

His print run was sub-miniscule. Duplicating his work was not an option, so Het Onderwater Cabaret circulated in its original form, passed from hand to hand at great risk.

The zine’s title is a play on onderduiken (to dive under), which Dutch people understood as a reference to the 10,000 Jews hiding from the Nazis in their country.

Gerard Groeneveld, author of The Underwater Cabaret: The Satirical Resistance of Curt Bloch, credits the “huge organization” who helped Bloch and others sequestered Jews with circulating the zine:

(It) included couriers, who brought food, but who could also bring the magazine out, to share with other people in the group who could be trusted. The magazines are very small, you can easily put one in your pocket or hide it in a book. He got them all back. They must have also returned them in some way.

It’s nothing short of a miracle that all 95 installments survive. Many zinesters fall short of preserving their work, but Bloch could not ignore this project’s personal and historical significance.

Aubrey Pomerance, co-curator of the Jüdisches Museum Berlin’s upcoming exhibit, “My Verses Are Like Dynamite, Curt Bloch’s Het Onderwater Cabaret”, notes that “the overwhelming majority of writings that were created in hiding were destroyed.”

For half a century, these zines were known to a select few — family members, their original readers, and a handful of guests whom Bloch entertained by reading passages aloud after dinner parties in the family’s New York home.

Pomerance suspects that Bloch always intended for his work to have a performance aspect, and that the couple who shared his crawlspace quarters may well have been his first audience for ditties like the one below.

Hyenas and jackals

Look on with jealousy

For they now seem as choirboys

Compared to humanity.

Bloch’s daughter, Simone, who describes her dad as a smartass, is working on a website dedicated to his work. Read more about Bloch’s zine at The New York Times.

The images on this page thanks to the generous support of the Bloch family; restoration and digitization comes thanks to the Jewish Museum Berlin.

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.