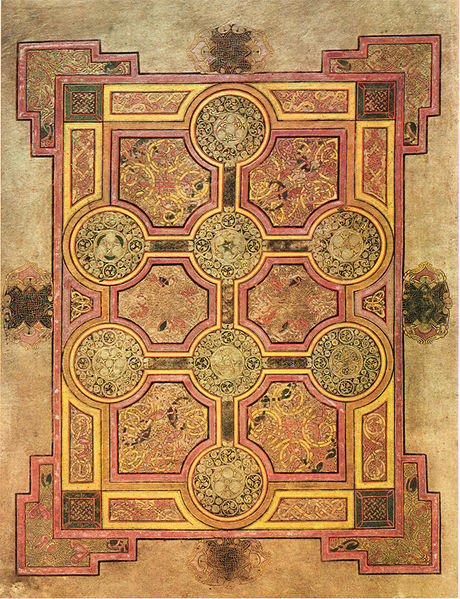

Whatever set of religious or cultural traditions you come from, you’ve probably seen a Celtic cross before. Unlike a conventional cross, it has a circular ring, or “nimbus,” where its arms and stem intersect. The sole addition of that element gives it a highly distinctive look, and indeed makes it one of the representative examples of Insular iconography — that is, iconography created within Great Britain and Ireland in the time after the Roman Empire. Perhaps the most artistically impressive Celtic cross in existence is found on one of the pages of the ninth-century Book of Kells (view online here), which itself stands as the most celebrated of all Insular illuminated manuscripts.

On what’s called the “carpet page” of the Book of Kells, explains Smarthistory’s Steven Zucker in the video above, “we see a cross so elaborate that it almost ceases to be a cross.” It has “two crossbeams, and these delicate circles with intricate interlacing in each of them, but the circles are so large that they almost overwhelm the cross itself.”

That’s hardly the only image of note in the book, which contains the four Gospels of the New Testament, among other texts, as well as numerous and extravagant illustrations, all of them executed painstakingly by hand on its vellum pages back when it was created, circa 800, in the scriptorium of a medieval monastery. These illustrations include, as Zucker’s colleague Lauren Kilroy puts it, “the earliest representation of the Virgin and Child in a manuscript in Western Europe.”

This is hardly a volume one approaches lightly — especially if one approaches it in person, as Zucker and Kilroy did on their visit to Trinity College Dublin. “When we were standing in front of the book,” says Kilroy, they “noticed how many folios formed the book itself” (which would have required the skin of more than 100 young calves). Coming to grips with the sheer quantity of material in the Book of Kells is one thing, but understanding how to interpret it is another still. Hence the free online course previously featured here on Open Culture, which can help you more fully appreciate the book in its digitized form available online. Even if the cross, Celtic or otherwise, stirs no particular religious feelings within you, the Book of Kells has much to say about the civilization that produced it: a civilization that, insular though it may once have been, would go on to change the shape of the world.

Related Content:

The Medieval Masterpiece the Book of Kells Is Now Digitized and Available Online

Take a Free Online Course on the Great Medieval Manuscript the Book of Kells

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.