Over the years, we’ve featured the work of William Blake fairly often here on Open Culture: his own illuminated books; his illustrations for everything from the Divine Comedy to Mary Wollstonecraft’s Original Stories from Real Life to the Book of Job; pairs of Doc Martens made out of his paintings Satan Smiting Job with Sore Boils and The House of Death. Blake continues to capture our imaginations, despite having lived in the very different world of the mid-eighteenth century to the mid-nineteenth — but then, he also lived in a world well apart from his contemporaries.

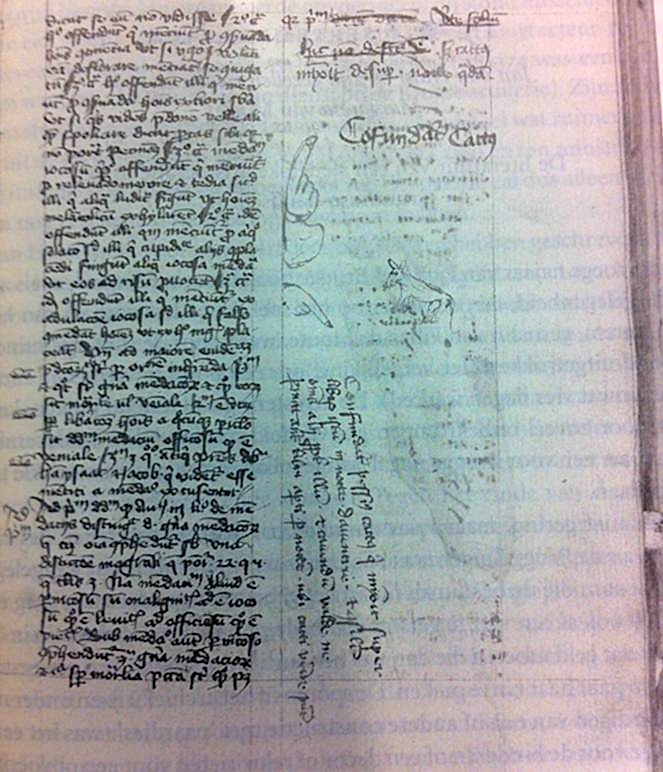

“Blake belonged to the Romantic age, but stands utterly alone in that age, both as an artist and as a poet,” says gallerist-Youtuber James Payne in his new Great Art Explained video above. “He is someone who invented his very own form of graphic art, which organically fused beautiful images with powerful poetry, while he also forged his own distinctive philosophical worldview and created an original cosmology of gods and spirits designed to express his ideas about love, freedom, nature, and the divine.” It wouldn’t be an exaggeration to call him a visionary, not least since he experienced actual visions throughout almost his entire life.

Not just a visual artist but “one of the greatest poets in the English language,” Blake produced a body of work in which word and image are inseparable. Though it “addresses contemporary subjects like social inequality and poverty, child exploitation, racial discrimination, and religious hypocrisy,” its worldliness is exceeded by its otherworldliness. What compels us is as much the power of art itself as the “vast and complicated mythology” underlying the project on which Blake worked until the very end of his life. His ideal was “liberty from tyranny in all forms,” political, religious, scientific, and any other kind besides; in pursuing it, he could hardly have limited himself to just one plane of existence.

Related content:

The Otherworldly Art of William Blake: An Introduction to the Visionary Poet and Painter

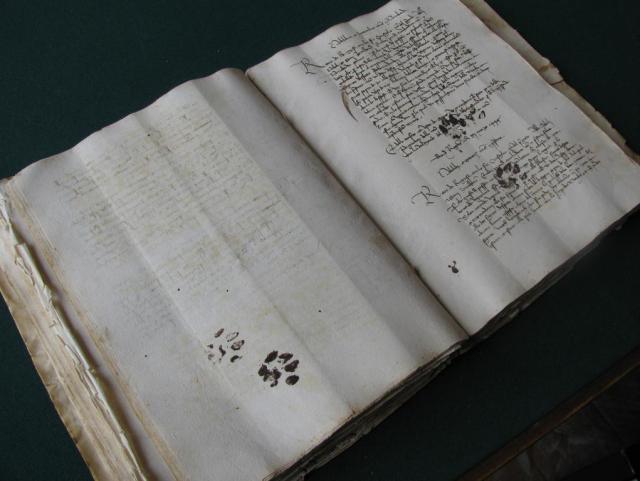

William Blake: The Remarkable Printing Process of the English Poet, Artist & Visionary

William Blake’s Hallucinatory Illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.