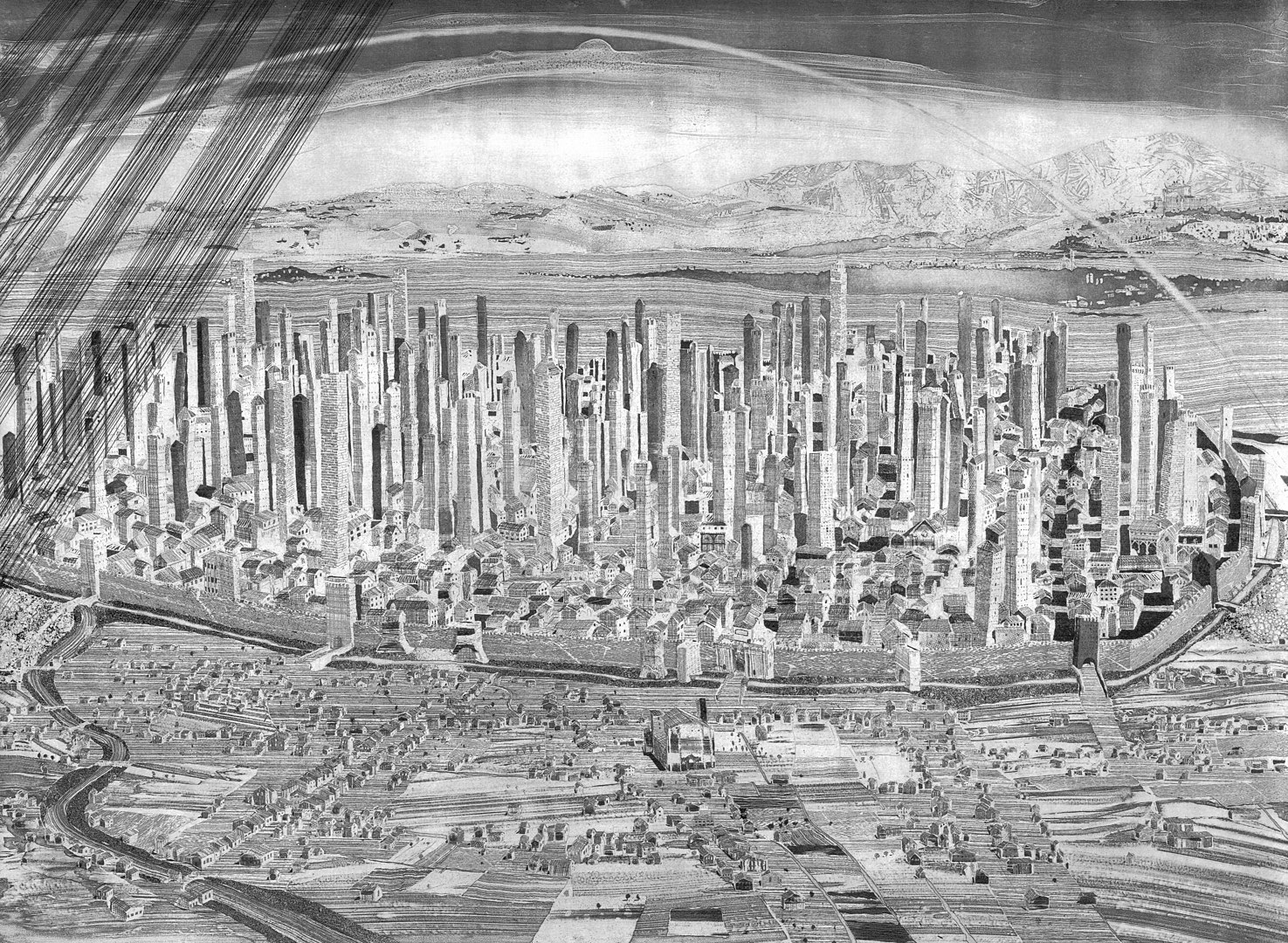

Image by Toni Pecoraro, via Wikimedia Commons

Go to practically any major city today, and you’ll notice that the buildings in certain areas are much taller than in others. That may sound trivially true, but what’s less obvious is that the height of those buildings tends to correspond to the value of the land on which they stand, which itself reflects the potential economic productivity to be realized by using as much vertical space as possible. To put it crudely, the taller the buildings in a part of town, the greater the wealth being generated (or, at times, destroyed). This is a modern phenomenon, but it also held true, in a different way, in the Bologna of 800 years ago.

There exists a work of art, much circulated online, that depicts what looks like the capital of Emilia-Romagna in the twelfth or thirteenth century. But the city bristles with what look like skyscrapers, creating an incongruous but enchanting medieval Blade Runner effect. Bologna really does have towers like that, but only about 22 of them still stand today. Whether it ever had the nearly 180 depicted in this particular image, and what happened to them if it did, is the question Jochem Boodt investigates in the Present Past video below.

In the era these towers were built, Bologna had become “one of the largest cities in Europe. It’s a time of huge, ambitious projects. Cities built cathedrals, town halls, and public squares — and some people built towers.” Those people included noble families who held to aristocratic traditions, not least violent feuding. Given that “the city is no place to build castles,” they instead inhabited urban complexes whose townhouses surrounded towers, which were “more like panic rooms” than actual living spaces. References to these prominent structures appear in subsequent works of art and literature: Dante, for instance, wrote of a leaning “tower called Garisenda.”

The etching that set Boodt on this journey to Bologna in the first place turns out to be the relatively recent work of an Italian artist called Toni Pecoraro, who heightened — in every sense — images of a 1917 model of the city by the shoemaker and “strange self-taught artist-scientist” Angelo Finelli. Finelli, in turn, drew his inspiration from a study by the nineteenth-century archaeologist Giovanni Gozzadini, himself a scion of one of those very families who competed to have the tallest tower, then got bored and pursued other status symbols instead. Perhaps Bologna is no longer the center of aristocratic and mercantile intrigue it used to be, judging by the sparseness of its current skyline, but then, there’s something to be said for not needing a fortified tower in which to hide at a moment’s notice.

Related content:

Why Europe Has So Few Skyscrapers

Why the Leaning Tower of Pisa Still Hasn’t Fallen Over, Even After 650 Years

Venice Explained: Its Architecture, Its Streets, Its Canals, and How Best to Experience Them All

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.