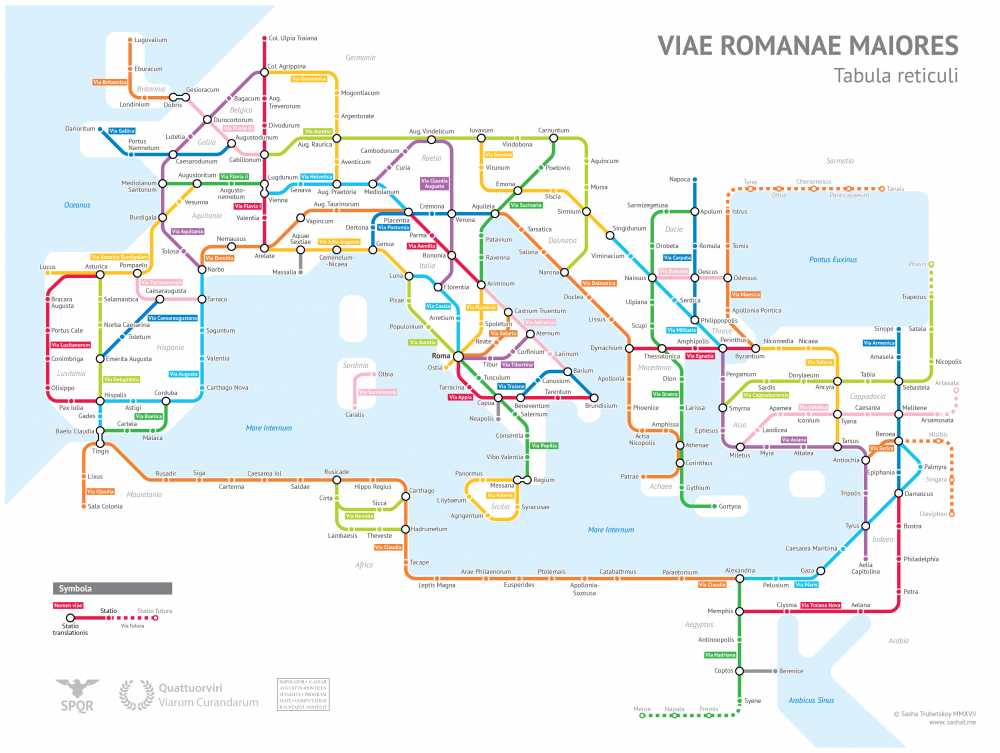

When the words London and underground come together, the first thing that comes to most of our minds, naturally, is the London Underground. But though it may enjoy the honorable distinction of the world’s first railway to run below the streets, the stalwart Tube is hardly the only thing buried below the city — and far indeed from the oldest. The video above makes a journey through various subterranean strata, starting with the paving stone and continuing through the soil, electric cables, and gas pipelines beneath. From there, things get Roman.

First comes the Billingsgate Roman House and Baths and the Roman amphitheater, two preserved places from what was once called Londinium. Below that level run several now-underground rivers, just above the depth of Winston Churchill’s private bunker, which is now maintained as a museum.

Farther down, at a depth of 66 feet, we find the remains of London’s tube system — not the Tube, but the pneumatic tube, a nineteenth-century technology that could fire encapsulated letters from one part of the city to another. More effective and longer lived was the later, more deeply installed London Post Office Railway, which was used to make deliveries until 2003.

At 79 feet underground, we finally meet with the Underground — or at least the first and shallowest of its eleven lines. The Tube has long become an essential part of the lives of most Londoners, but around the same depth exists another facility known to relatively few: the Camden catacombs, a system of underground passages once used to stable the horses who worked on the railways. Further down are the network of World War II-era “deep shelters,” one of which hosted the planning of D‑Day; below them is a still-functional facility instrumental to the defeat of different enemies, typhus and cholera. That would be London’s sewer system, for which we should spare a thought if we’ve ever walked along the Thames and appreciated the fact that it no longer stinks.

Related content:

The Lost Neighborhood Buried Under New York City’s Central Park

Undercity: Exploring the Underbelly of New York City

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.