Hate the sin, never the sinner. — Clarence Darrow

As a culture, we’ve largely stepped away from the sentiment described by the famed lawyer’s 1924 defense of murderers Leopold and Loeb.

Apply it to one of the many male artists whose exalted reputations have been shattered by allegations of sexual impropriety and other ruinous behaviors and you won’t find yourself celebrated for your virtue in the court of public opinion.

But what of those artists’ creative output?

Does that get bundled in with hating both sin and sinner?

It’s a question that historian and former curator Sarah Urist Green is well equipped to tackle.

Green’s PBS Digital Studios web series, The Art Assignment, explores art and art history through the lens of the present.

In the episode titled Hate the Artist, Love the Art, above, Green takes a more temperate approach to the subject than comedian Hannah Gadsby, whose solo show, Nanette, included an incendiary takedown of Picasso:

I hate Picasso. and you can’t make me like him. I know I should be more generous about him too, because he suffered a mental illness. But nobody knows that, because it doesn’t fit with his mythology. Picasso is sold to us as this passionate, tormented, genius, man-ball-sack. But Picasso suffered the mental illness…of misogyny.

Don’t believe me? He said, “Each time I leave a woman, I should burn her. Destroy the woman, you destroy the past she represents.” Cool guy. The greatest artist of the 20th century. Picasso fucked an underage girl. That’s it for me, not interested.

But Cubism! He made it! Marie-Thérèse Walter, she was 17 when they met: underage. Picasso, he was 42, at the height of his career. Does it matter? It actually does matter. But as Picasso said, “It was perfect—I was in my prime, she was in her prime.” I probably read that when I was 17. Do you know how grim that was?

Grim.

A different sort of grim than the horrors he depicted in Guernica, still an incredibly potent condemnation of the human cost of war.

Should exemptions be made, then, for works of great genius or lasting social import?

Up to you, says Green, advocating that every viewer should pause to consider the ripples caused by their continued embrace of a disgraced artist.

But what if we don’t know that the artist’s been disgraced?

That seems unlikely as curators scramble to acknowledge the offender’s transgressions on gallery cards, and emergent artists attempt to set the record straight with response pieces displayed in proximity.

Green notes that even without such overt cues, it’s very difficult to get a “pure” reading of an established artist’s work.

Anything we may have gleaned about the artist’s personal conduct, whether good or ill, proven, unproven, or disproven, factors into the way we experience that artist’s work. The source can be a paper of record, the Internet, a guest at a party repeating a personal anecdote…

It can also be painful to relinquish our youthful favorites’ hold on us, especially when the attachment was formed of our own free will.

What would Hannah Gadsby say to my reluctance to sever ties completely with Gauguin’s Tahiti paintings, encountered for the first time when I was approximately the same age as the brown-skinned teenaged muses he painted and took to bed?

The behavior that was once framed as evidence of an artistic spirit that could not be fettered by societal expectations, seems beyond justification today. Still, it’s unlikely Gauguin will be banished from major collections, or for that matter, the history of art, any time soon.

As Julia Halperin, executive editor of Artnet News observed shortly after Nanette became a viral sensation:

A Netflix comedy special is not going to compel museums to throw out their Picassos. Nor should they! You can’t tell the story of 20th-century art without him…. Although glossing over, whitewashing, or shoe-horning stories of Picasso’s abuse into a comfortable narrative about passionate genius may be useful to maintain his market value and his bankability as a tourist attraction, it also does everyone a disservice… we can understand Picasso’s contributions better if we can hold these two seemingly incompatible truths in our minds at once. It’s not as uplifting as a straightforward tale about a visionary creative whose flaws were only in service to its genius. But it is more honest—and it might even help us understand the evolution of our own culture, and how we got to where we are today, a lot better.

Green provides a list of questions that can help individual viewers who are reevaluating the output of “problematic” artists:

Is the work a collaborative effort?

Does the work reflect the value system of the offender?

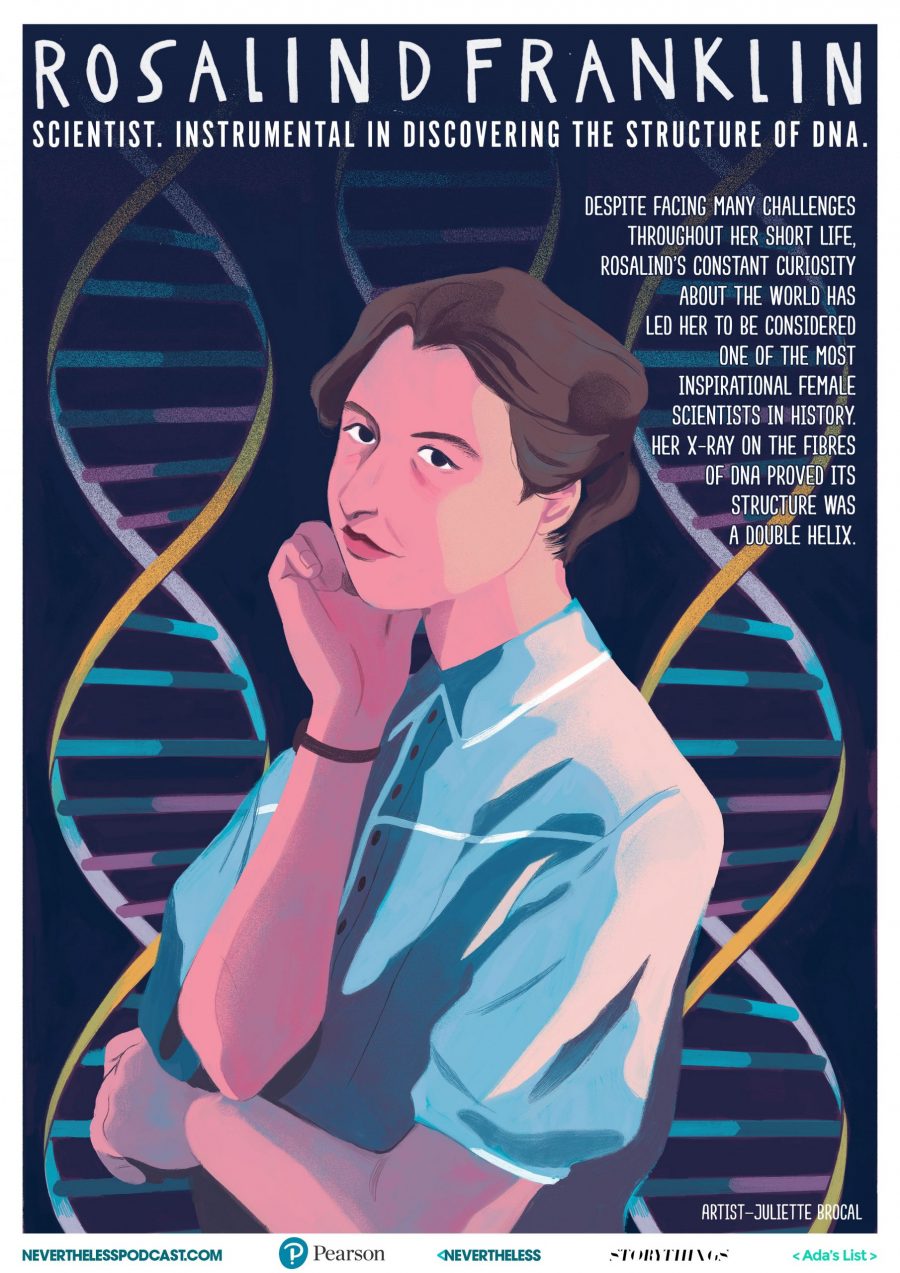

Are we to apply the same standard to the work of scientists whose conduct is similarly offensive?

Who suffers when the offender’s work remains accessible?

Who suffers when the offender’s work is erased?

Who reaps the reward of our continued attention?

As Green points out, the shades of grey are many, though the choice of whether to entertain those shades varies from individual to individual.

Readers, where do you fall in this ever-evolving debate. Is there an artist you have sworn off of, entirely or in part? Tell us who and why in the comments.

Watch more episodes of the Art Assignment here.

Related Content:

George Orwell Reviews Salvador Dali’s Autobiography: “Dali is a Good Draughtsman and a Disgusting Human Being” (1944)

When The Surrealists Expelled Salvador Dalí for “the Glorification of Hitlerian Fascism” (1934)

The Gestapo Points to Guernica and Asks Picasso, “Did You Do This?;” Picasso Replies “No, You Did!”

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, January 6 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domaincelebrates Cape-Coddities (1920) by Roger Livingston Scaife. Follow her @AyunHalliday.