I don’t know about you, but when I’ve thought of chess grandmasters, I’ve often thought of Russians, northern Europeans, the occasional American, the guy on the Chessmaster box — purely by stereotype, in other words. I’ve never thought of anyone from, say, Jamaica, the country of birth of Maurice Ashley, not just a chess grandmaster but a chess commentator, writer, app and puzzle designer, speaker and Fellow at the Media Lab at MIT. Since we’ve only just entered February, known in the United States as Black History Month, why not highlight the Brooklyn-raised (and Brooklyn-park trained) Ashley’s status as, in the words of his official web site, “the first African-American International Grandmaster in the annals of the game”?

Given the impressiveness of his achievements, we might also ask what we can learn from him, whether or not we play chess ourselves. You can learn a bit more about Ashley, the work he does, and the work his students have gone on to do, in The World Is a Chess Board, the five-minute Mashable documentary at the top of the post. Even in that short runtime, he has much to say about how the game (which, he clarifies, “we consider an art form”) not only reflects life, and reflects the personalities of its players, but teaches those players — especially the young ones who may come from less-than-ideal beginnings — all about focus, determination, choice, and consequence. Perhaps the most important lesson? “You’ve got to be ready to lose.”

Ashley expounds upon the value of chess as a tool to hone the mind in “Working Backward to Solve Problems,” a clip from his TED Ed lesson just above. He begins by waving off the misperception, common among non-chess-players, that grandmasters “see ahead” ten, twenty, or thirty moves into the game, then goes on to explain that the sharpest players do it not by looking forward, but by looking backward. He provides a few examples of how using this sort of “retrograde analysis,” combined with pattern recognition, applies to problems in a range of situations from proofreading to biology to law enforcement to card tricks. If you ever have a chance to enter into a bet with this man, don’t.

That’s my advice, anyway. As far as Ashley’s advice goes, if we endorse any particular takeaway from what he says here, we endorse the first step of his chess-learning strategy for absolute beginners, which works equally well as the first step of a learning strategy for absolute beginners in anything: “The best advice I could give a young person today is, go online and watch some videos.” Stick with us, and we’ll keep you in all the videos you need.

Related Content:

Kasparov Talks Chess, Technology and a Little Life at Google

Free App Lets You Play Chess With 23-Year-Old Norwegian World Champion Magnus Carlsen

Watch Bill Gates Lose a Chess Match in 79 Seconds to the New World Chess Champion Magnus Carlsen

A Famous Chess Match from 1910 Reenacted with Claymation

Chess Rivals Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky Meet in the ‘Match of the Century’

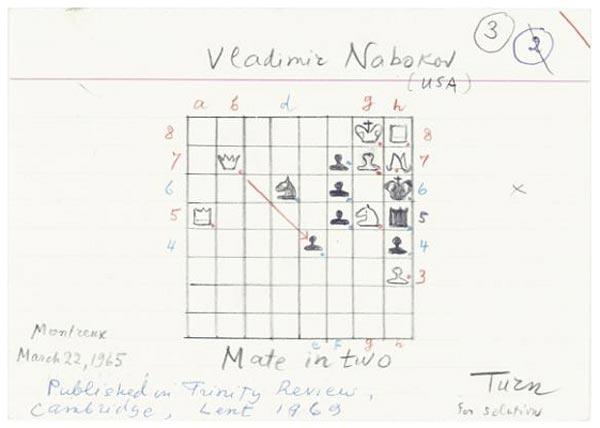

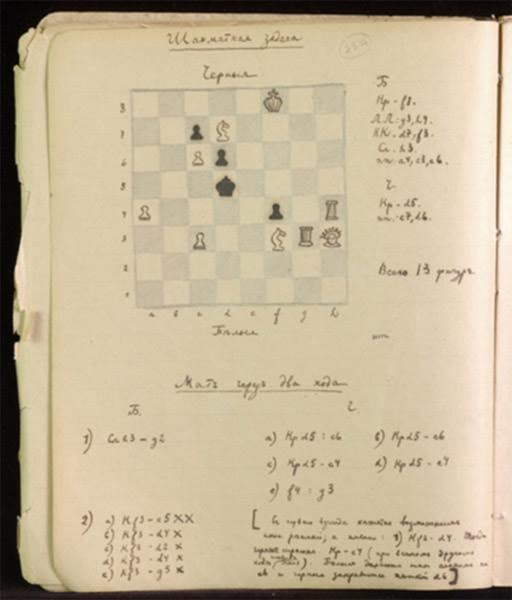

Vladimir Nabokov’s Hand-Drawn Sketches of Mind-Bending Chess Problems

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.