When it comes to chili, Texas, Kansas City and Cincinnati, will cede no quarter, each convinced that their particular regional approach is the only sane option.

Hot dogs? Put New York City and Chicago in a pit and watch them tear each other to ribbons.

But pizza?

There are so many geographic variations, even an impartial judge can’t see their way through to a clear victor.

The playing field’s thick as stuffed pizza, a polarizing Chicago local specialty that’s deeper than the deepest dish.

Weird History Food’s whirlwind video tour of Every Pizza Style We Could Find In the United States, above, savors the ways in which various pizza styles evolved from the Neapolitan pie that Italian immigrant Gennaro Lombardi introduced to New York City in 1905.

Wait, though. We all have an acquaintance who takes perverse pleasure in offbeat topping choices — looking at you, California — but other than that, isn’t pizza just sauce, dough, and cheese?

How much room does that leave for variation?

Plenty as it turns out.

Crusts, thick or thin, fluctuate wildly according to the type of flour used, how long the dough is proofed, the type of oven in which they’re baked, and philosophy of sauce placement.

(In Buffalo, New York, pizzas are sauced right up to their circumference, leaving very little crusty handle for eating on the fly, though perhaps one could fold it down the middle, as we do in the city 372 miles to the south.)

Sauce can also swing pretty wildly — sweet, spicy, prepared in advance, or left to the last minute — but cheese is a much hotter topic.

Detroit’s pizza is distinguished by the inclusion of Wisconsin brick cheese.

St. Louis is loyal to Provel cheese, a homegrown processed mix of cheddar, Swiss, and provolone and liquid smoke.

Miami pizzas cater to the palates of its Cuban population by mixing mozzarella with gouda, a cheese that was both widely available and popular before 1962’s rationing system was put in place.

Rhode Island’s aptly named Red Strips have no cheese at all…which might be preferable to the Altoona, Pennsylvania favorite that arrives topped with American cheese slices or — the horror — Velveeta.

(This may be where we part ways with the old saw equating pizza with sex — even when it’s bad, it’s still pretty good.)

Cut and size also factor in to pizza pride.

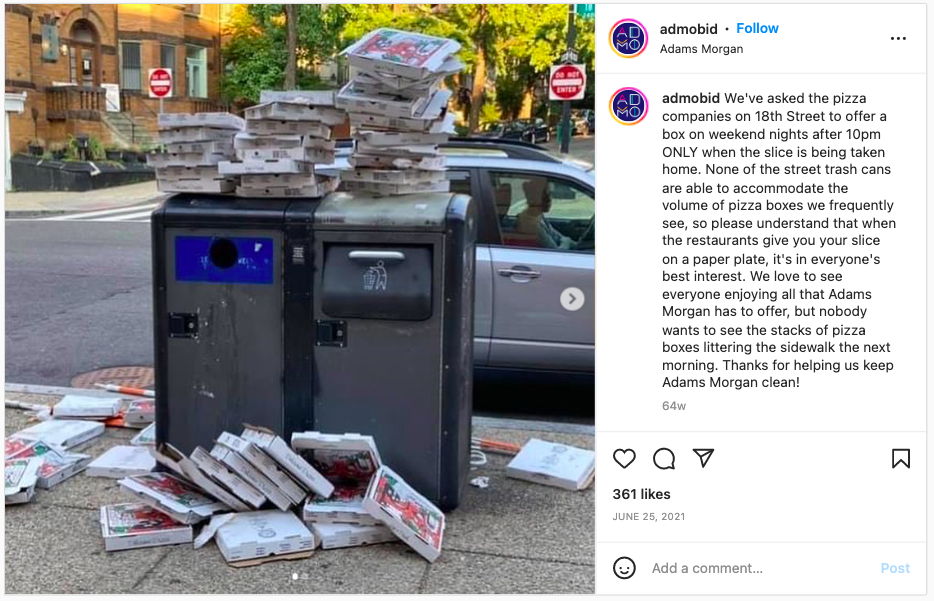

Washington DC’s Jumbo slices are pretty much the standard issue New York-style thin crust slice, writ large.

Not only does size matter here, it may be the only thing that matters…to the point where a local business improvement district had to intervene on behalf of sidewalk rubbish bins hard pressed to handle the volume of greasy super-sized slice boxes Washingtonians were tossing away every evening.

In the land of opportunity, where smaller towns are understandably eager to claim their piece of pie, Weird History Food gives the nod to Old Forge, Pennsylvania, optimistically dubbed “the Pizza Capital of the World by Uncovering PA’s Jim Cheney, and Steubenville Ohio, home of the “oversized Lunchable” Atlas Obscura refers to as America’s most misunderstood pizza.

For good measure, watch the PBS Idea Channel’s History of Pizza in 8 slices, below, then rep your favorite local pizzeria in the comments.

We want to try them all!

Related Content

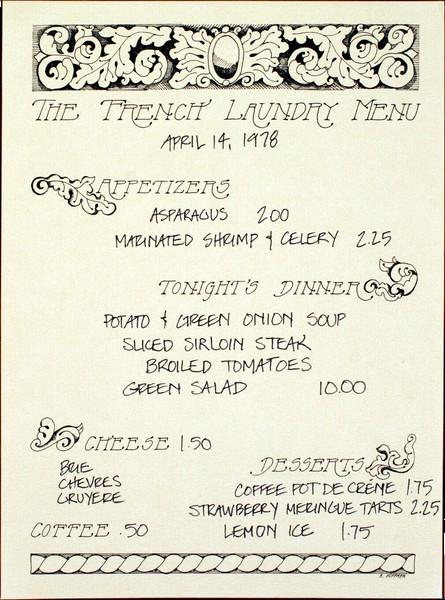

The First Pizza Ordered by Computer, 1974

When Mikhail Gorbachev, the Last Soviet Leader, Starred in a Pizza Hut Commercial (1998)

Pizza Box Becomes a Playable DJ Turntable Through the Magic of Conductive Ink

- Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto. Follow her @AyunHalliday.