But when from a long-distant past nothing subsists, after the people are dead, after the things are broken and scattered, still, alone, more fragile, but with more vitality, more unsubstantial, more persistent, more faithful, the smell and taste of things remain poised a long time, like souls, ready to remind us, waiting and hoping for their moment, amid the ruins of all the rest; and bear unfaltering, in the tiny and almost impalpable drop of their essence, the vast structure of recollection. — Marcel Proust, Swann’s Way

History favors the eyes.

Visual art can tell us what individuals who died long before the advent of photography looked like, as well as the sort of fashions, food and decor one might encounter in households both opulent and humble.

Our ears are also privileged in this regard, whether we’re listening to a Gregorian chant performed in a cathedral or an ace sound designer’s cinematic recreation of the D‑Day landings.

With a few judicious ingredient substitutions, we can even get a sense of what an Ancient Roman salad, a 4000-year-old Babylonian stew, and a 5000-year-old Chinese beer tasted like.

Pity the poor neglected nose. Scents are ephemeral! How often have we wondered what Versailles really smelled back in the 17th century, when unbathed aristocrats in unlaundered finery packed into high society’s unventilated salons?

On the other hand, given the opportunity, do we really want to know?

Odeuropa, the European olfactory heritage project, answers with a resounding yes.

Among its initiatives is an interactive Smell Explorer that invites visitors to dive deep into smells as cultural phenomena.

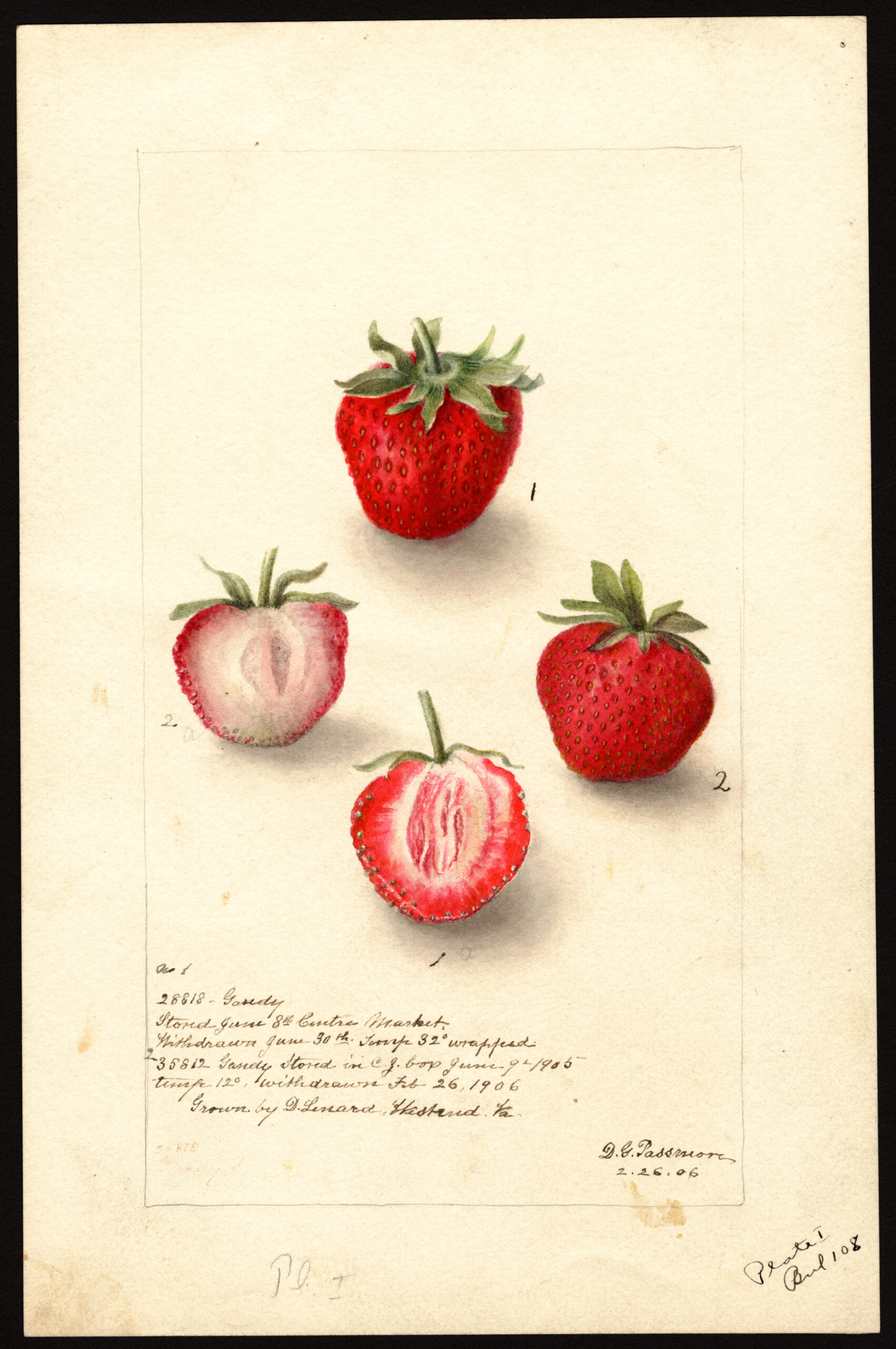

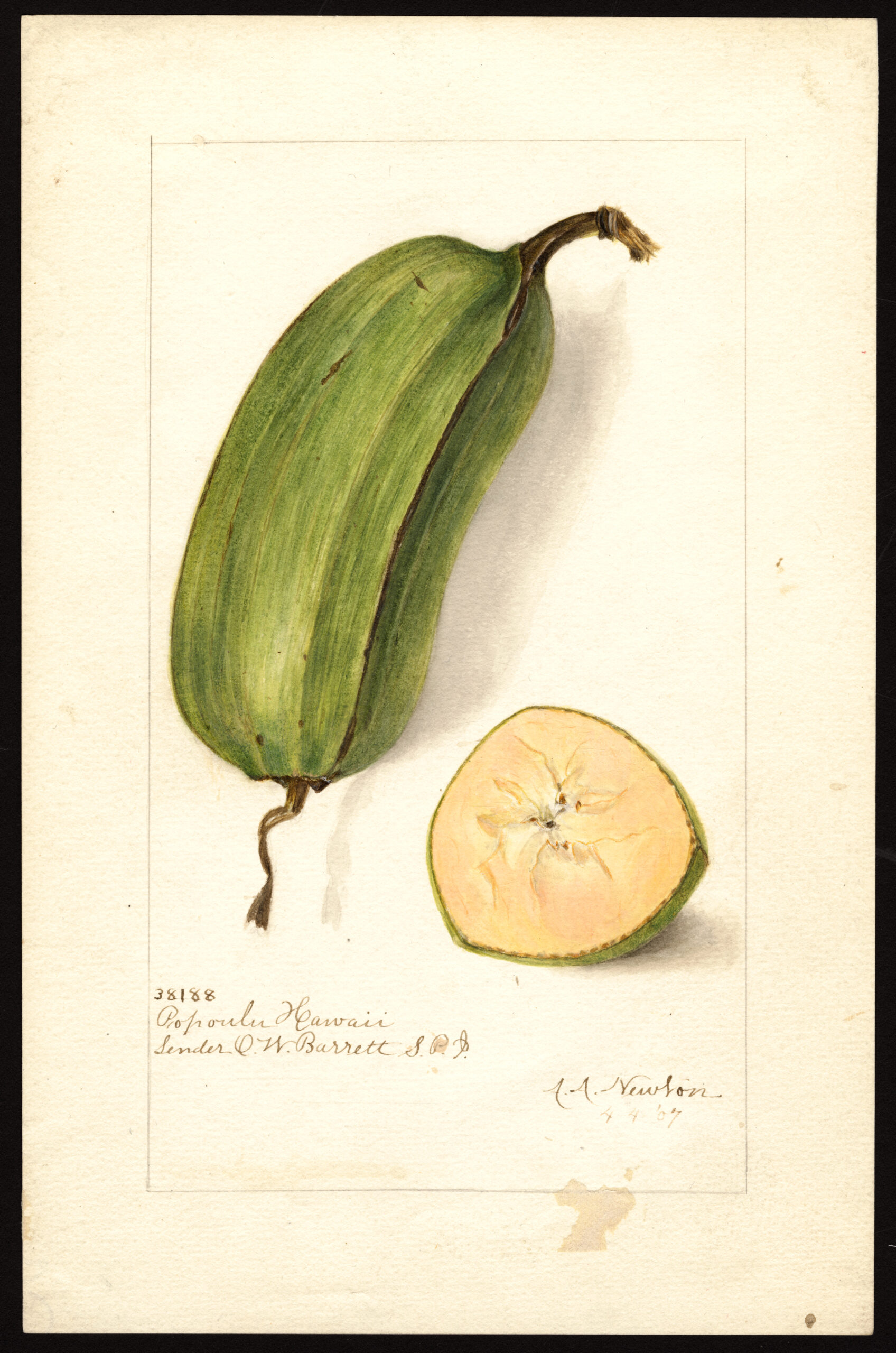

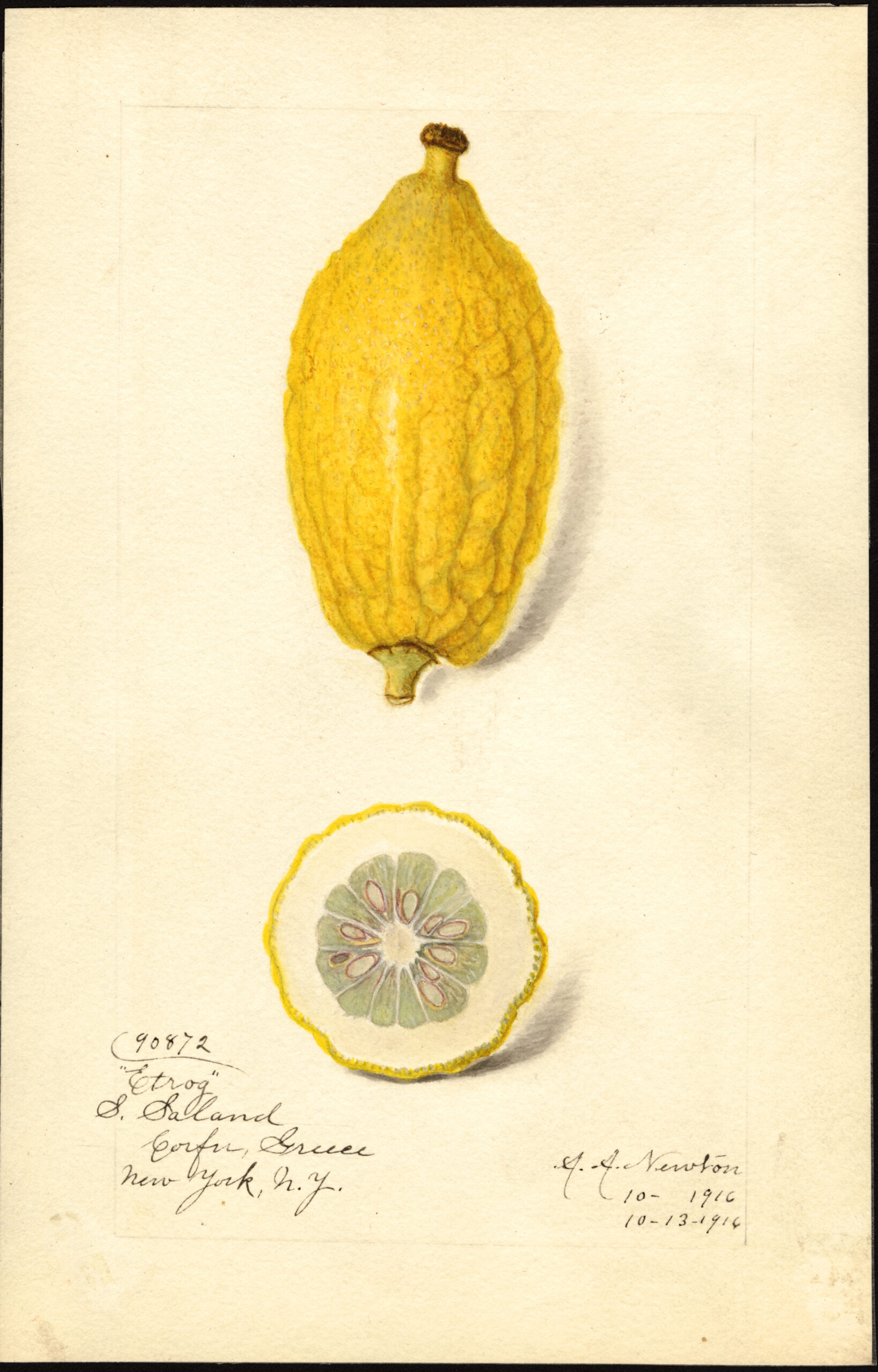

Developed by an international team of computer scientists, AI experts and humanities scholars, the Smell Explorer is a vast compendium of smells as represented in 23,000 images and 62,000 public domain texts, including novels, theatrical scripts, travelogues, botanical textbooks, court records, sanitary reports, sermons, and medical handbooks.

This resource offers a fresh lens for considering the past through our noses, an unflinching look at various olfactory realities of life in Europe from the 15th through early 20th centuries.

Survivors of earlier plagues and pandemics might have associated their trials with the purifying aromas of burning rosemary and hot tar, just as the scents of sourdough and the way a handsewn cotton face mask’s interior smelled after several hours of wear conjure the early days of the Covid-19 pandemic for many of us.

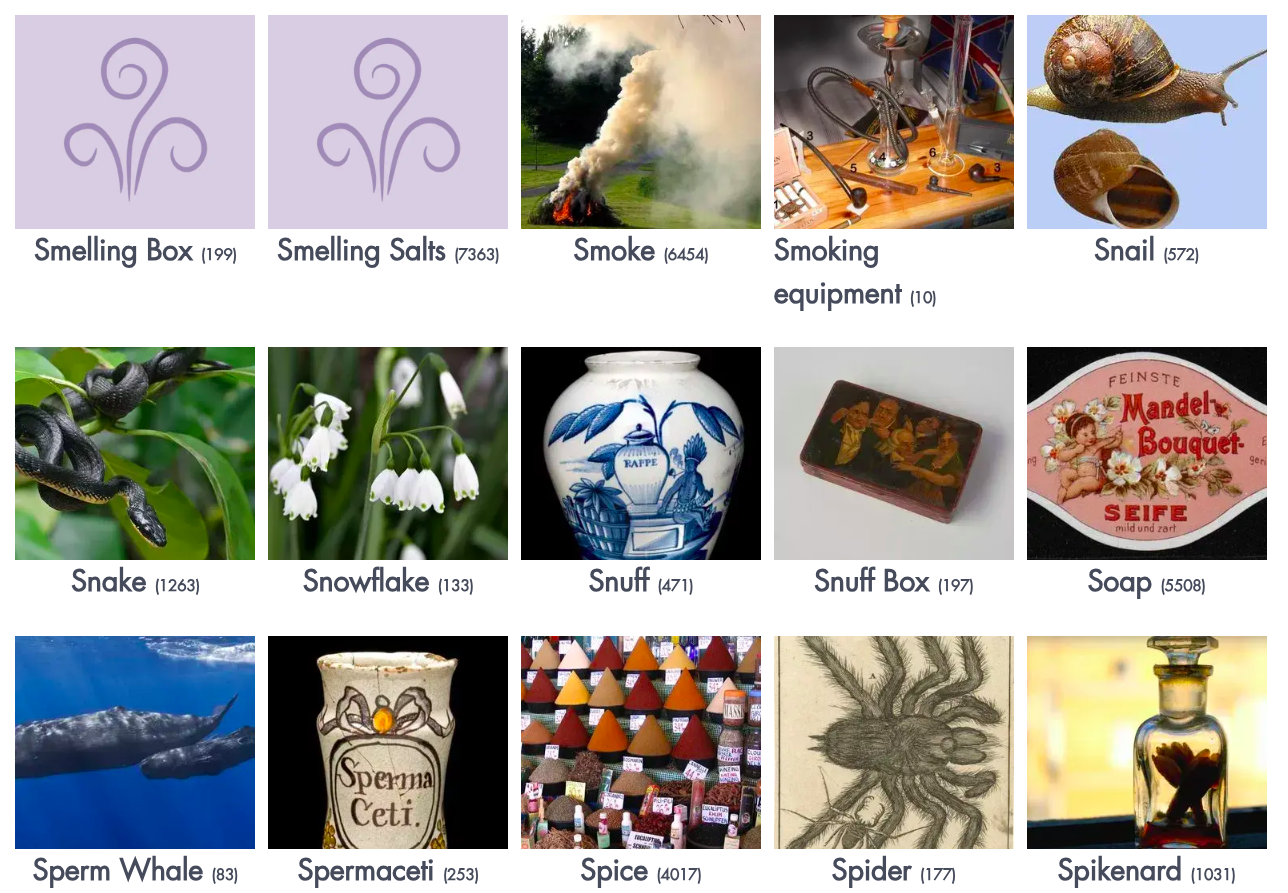

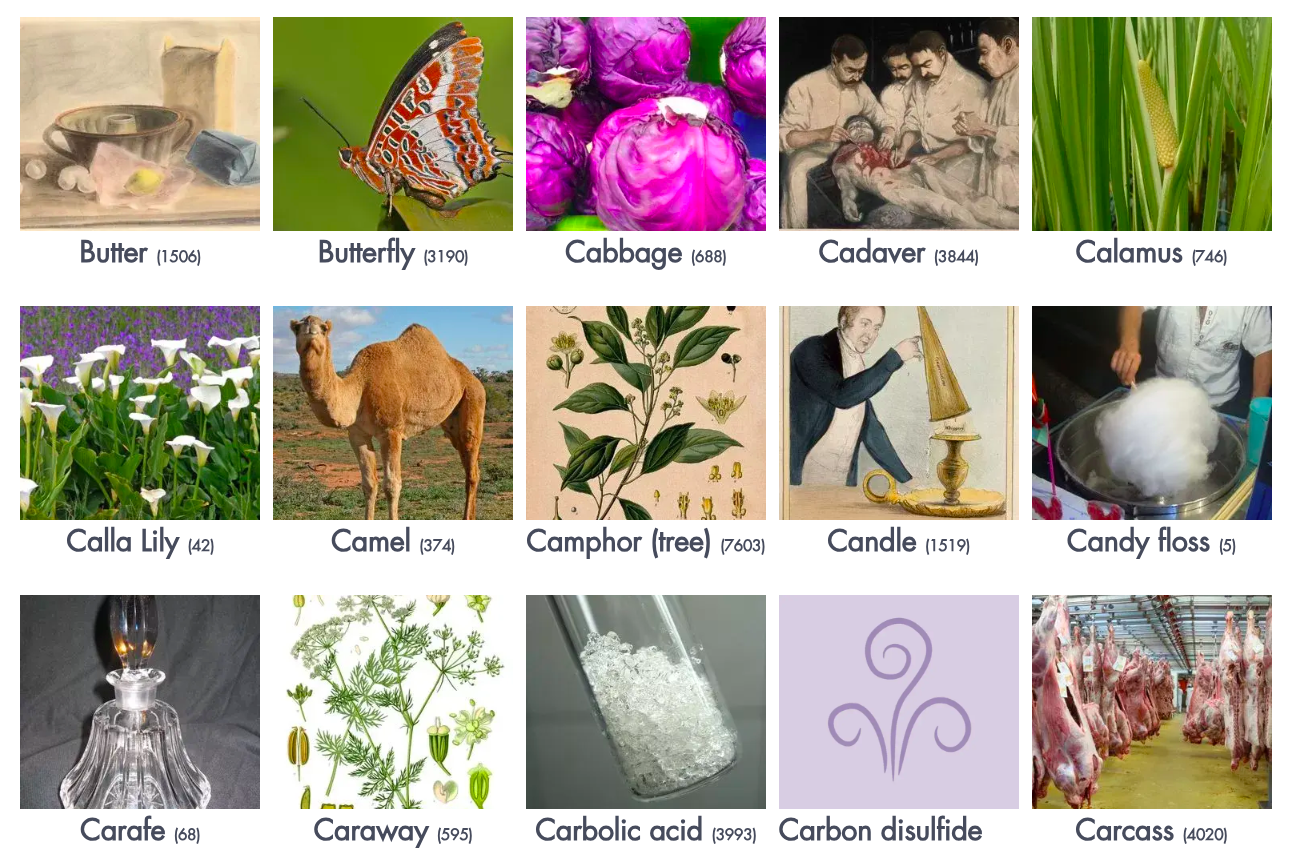

There are a number of interesting ways to explore this scent-rich database — by geographic location, time period, associated emotion, or aromatic quality.

Of course, you could go straight to a smell source.

“Chamber pot” returns 18,152 results, “cadaver“266…

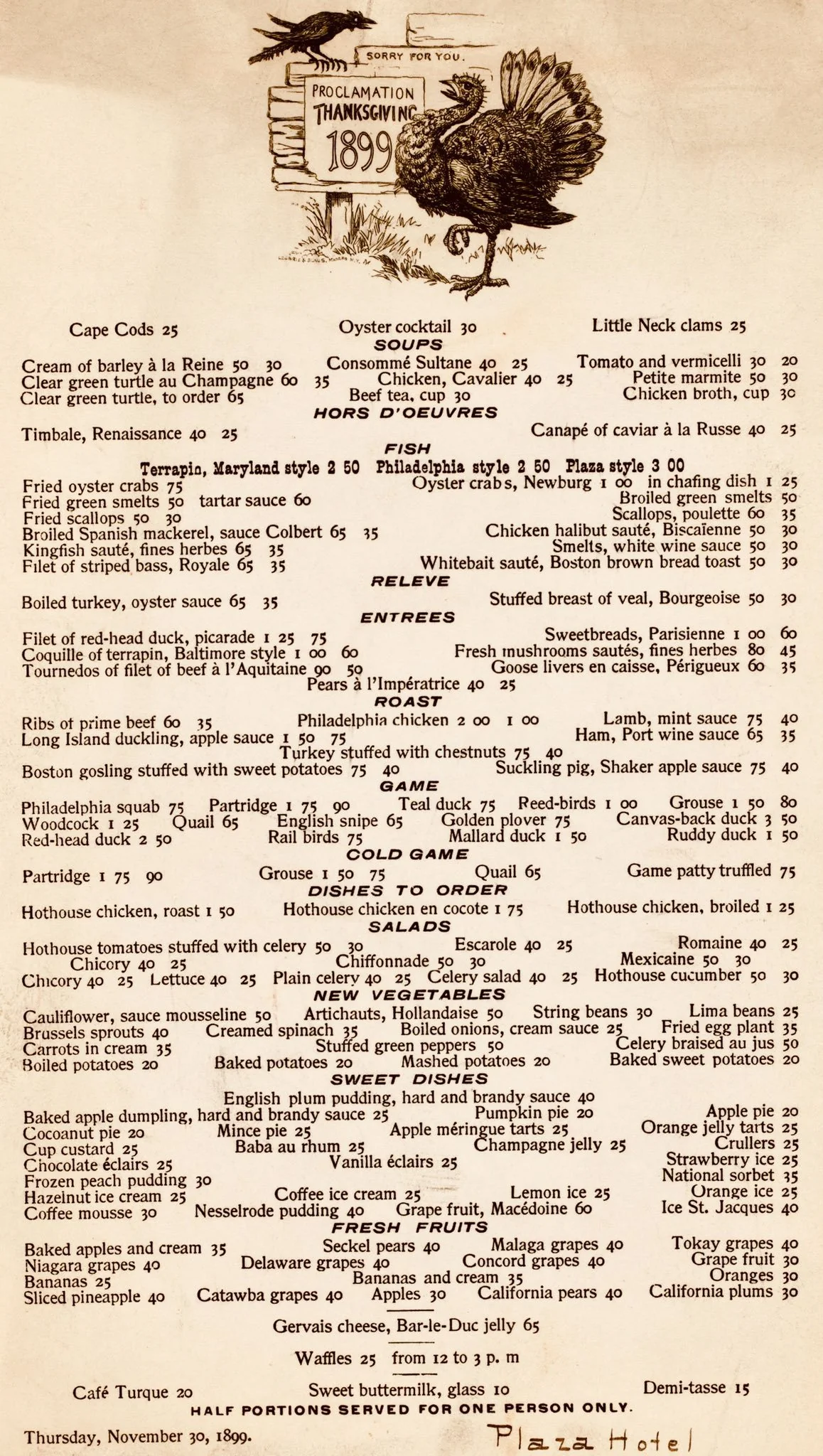

The squeamish are advised to steer clear of vomit (421 results) in favor of the Smell Explorer’s pleasurable and abundant food-related entries — bread, chocolate, coffee, pomegranate, pastry, and wine, to name but a few.

Each scent is built as a collection of cards or “nose witness reports” with information as to the title of the work cited, its author or artist, year of creation and characterization (“good”, “rank”, “peculiarly unpleasant and permanent”…)

Even more ambitiously, Odeuropa aims to give 21st-century noses an actual whiff of Europe’s olfactory heritage by enlisting perfumers and scent designers to recreate over a hundred historic odors and aromas.

Odeuropa has also created a downloadable Olfactory Storytelling Toolkit to give museum curators ideas for integrating culturally significant odors into exhibits, a trend that is gaining traction worldwide.

While everyone stands to benefit from the added olfactory dimension of such exhibits, this initiative is of particular service to blind and visually-impaired visitors. Expertise is no doubt required to get it right.

We’re reminded of satirist PJ O’Rourke early-80’s visit to the Exxon-sponsored Universe of Energy Pavilion in Walt Disney World’s EPCOT center, where animatronic dinosaurs were “depicted without accuracy and much too close to your face:”

One of the few real novelties at Epcot is the use of smell to aggravate illusions. Of course, no one knows what dinosaurs smelled like, but Exxon has decided they smelled bad.

Enter the Odeuropa Smell Explorer here.

Related Content

The Chemistry Behind the Smell of Old Books: Explained with a Free Infographic

– Ayun Halliday is the Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine and author, most recently, of Creative, Not Famous: The Small Potato Manifesto and Creative, Not Famous Activity Book. Follow her @AyunHalliday.