It’s a myth that starving artists don’t eat.

They do, just not often or well. Their meals rarely rate recipes, let alone cookbooks.

Those cookbooks do exist though.…

The mostly conceptual Starving Artist Cookbook put together by EIDIA (aka artists Paul Lamarre and Melissa Wolf) comes close to the spirit of sustaining life through meager ingredients… like spaghetti or 4 pages of shredded Pravda.

Not so this other title, which approaches cute overload with an abundance of Instagram-worthy illustrated fare—mojitos, an unstructured berry tart, a “manly” burger.…

Do “starving” artists no longer fear being outed as posers?

Successful artists may not worry about that, as they eat whatever and however they want.

Andy Warhol had the taste of an eccentric child.

Marina Abramović takes the ascetic route.

Many have glady traded the candle in the chianti bottle for the most rarified restaurants in town.

Georgia O’Keefe and Frida Kahlo, PBS Digital Studios’ series the Art Assignment informs us, took cooking—and eating—seriously.

So seriously, their culinary efforts led to cookbooks, which the Art Assignment’s host, curator Sarah Urist Green, tries out on camera.

O’Keefe, who grew up in Wisconsin on homemade yogurt, homemade cheese, and plentiful homegrown produce, ground her own flour in order to bake daily loaves of whole wheat bread.

Green treats viewers to a brief overview of O’Keefe’s life and work as she struggles with the grinder. (You might get the same, or better, results if you take a $5 bill to a good bakery right at opening.)

She also tackles the wheat germ Tiger’s Milk smoothie advocated by Adele Davis, a nutritionist whom O’Keefe admired, and Green Chiles with Garlic and Oil and Fried Eggs, using recipes from the cookbooks A Painter’s Kitchen and Dinner with Georgia O’Keefe.

Before attempting the same, you might want to watch the Kahlo-centric episode, above, in which Green discovers a much better method for roasting the poblano peppers she haplessly substituted for New Mexico chiles in O’Keefe’s egg dish.

Here, they’re used for Chiles Rellenos, a dish whose pronunciation the self-effacing Green butchers, along with a multitude of other Spanish phrases, a fact not lost on the video’s Youtube commenters. They also take issue with the presence of plantains, her preparation of the Nopales Salad, and her cooking skills in general. No wonder Green—a self-proclaimed wussy where serranos are concerned—seems so eager to reach for a shot of tequila as dinner is finally served.

Green chose the dishes for this episode from Frida’s Fiestas: Recipes and Reminiscences of Life with Frida Kahlo by Marie-Pierre Colle and Kahlo’s stepdaughter, Guadalupe Rivera.

Kahlo herself learned to cook from her mother’s copy of El Nuevo Cocinero Mejicano, and from husband Diego Rivera’s first wife, Guadalupe (leading one to wonder if some of that cookbook’s recipes aren’t misattributed to the more famous cook).

As with the O’Keefe video and the cookbooks cited herein, there’s a wealth of vintage photos and reproduced artwork on display.

Even though Green alludes to Kahlo’s dark side, sensitive stomachs might have trouble with the inclusion of the graphically violent Unos Quantos Piquetitos. Another painting, My Nurse and I is at least related to eating, if not cooking and recipes.

Those with stomachs of steel on the other hand can continue on to another Art Assignment—the supremely gross Meat Sculpture from the Futurist Cookbook.

Related Content:

The Futurist Cookbook (1930) Tried to Turn Italian Cuisine into Modern Art

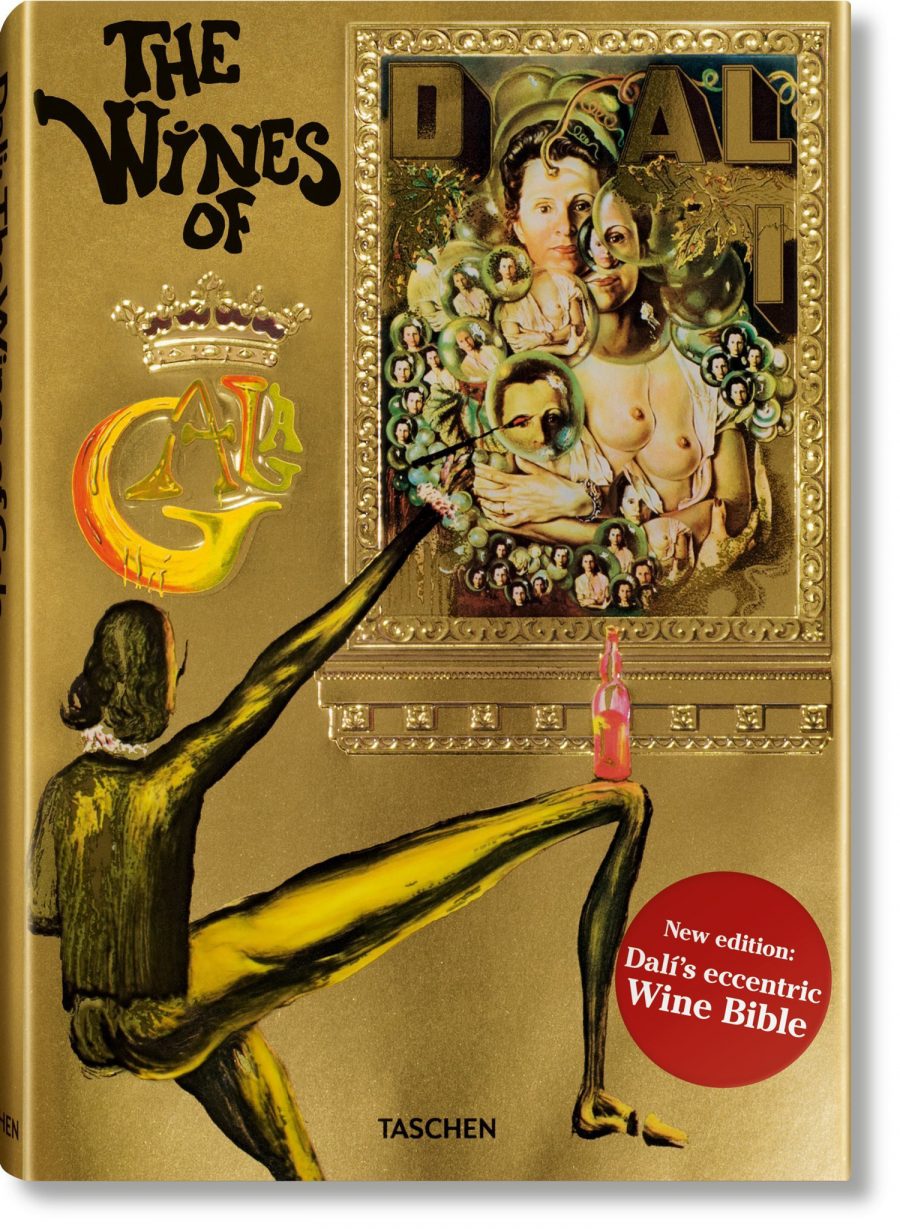

MoMA’s Artists’ Cookbook (1978) Reveals the Meals of Salvador Dalí, Willem de Kooning, Andy Warhol, Louise Bourgeois & More

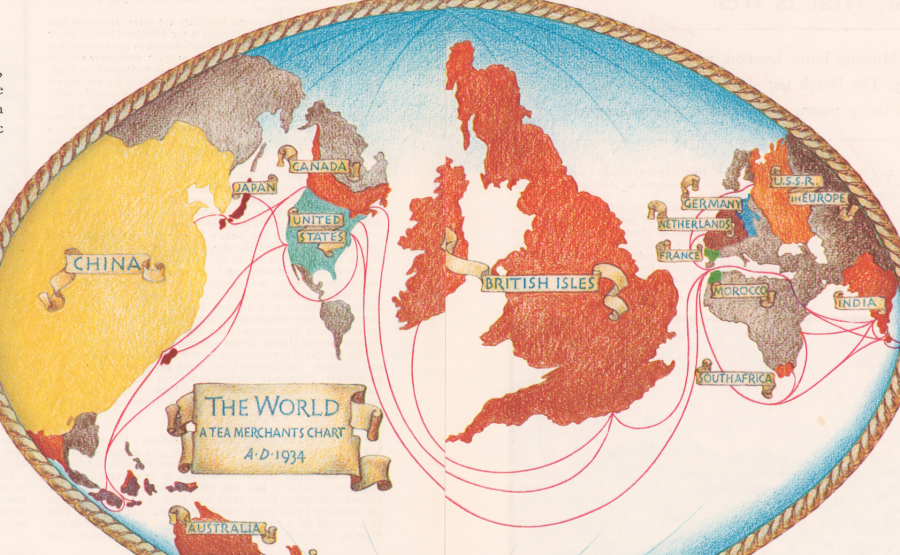

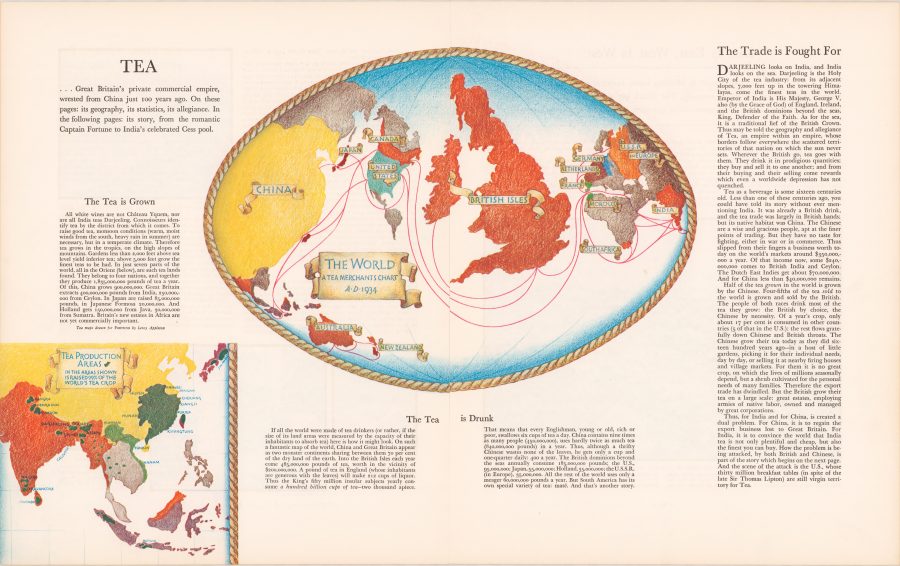

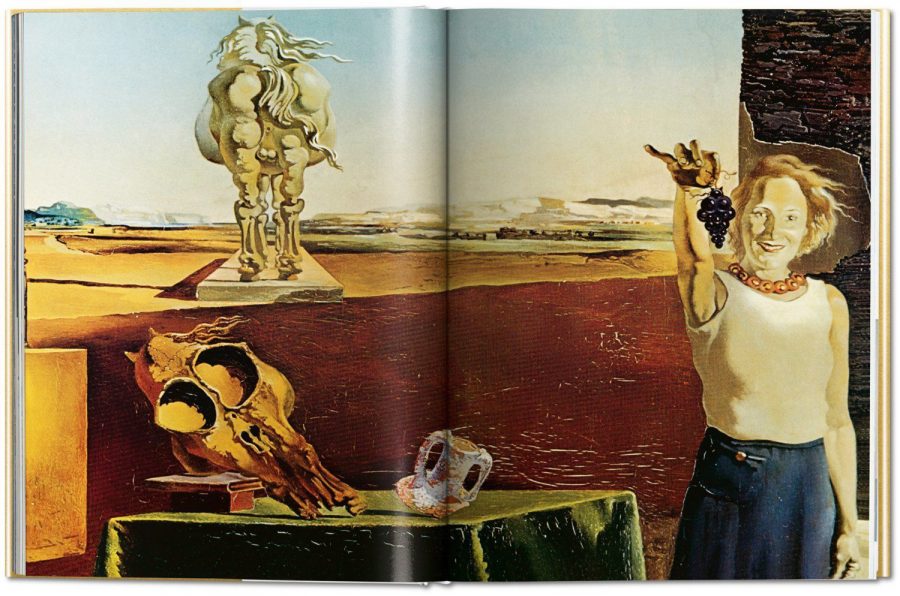

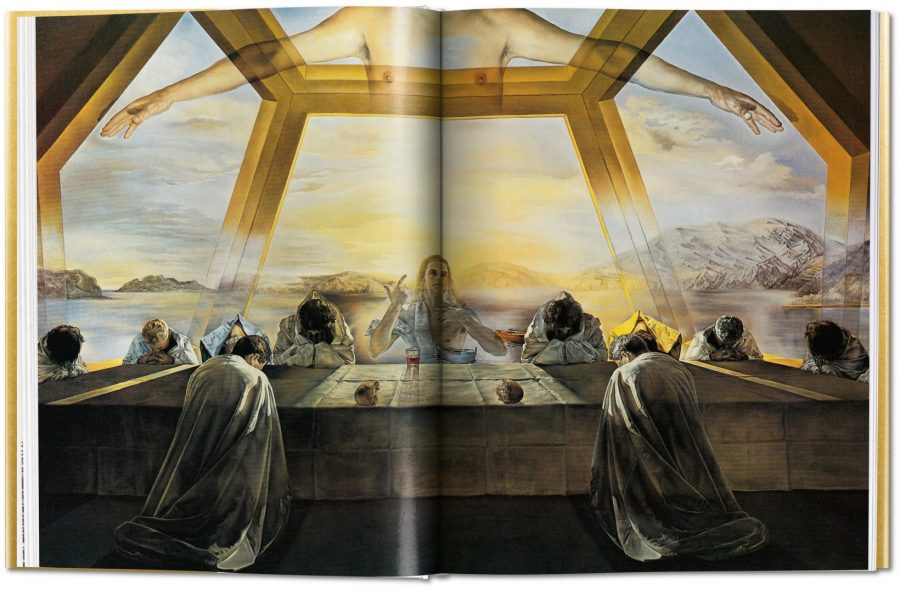

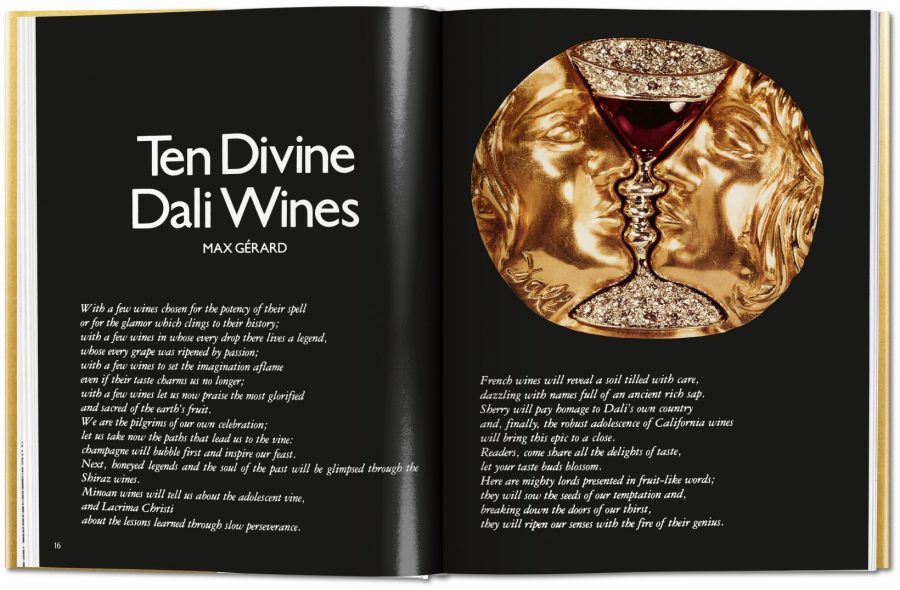

Salvador Dalí’s 1973 Cookbook Gets Reissued: Surrealist Art Meets Haute Cuisine

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Discuss Emily Dickinson with her informally at Pete’s Mini Zinefest in Brooklyn this Saturday. Follow her @AyunHalliday.