Image via Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports

Back in 2017, we featured the oldest unopened bottle of wine in the world here on Open Culture. Found in Speyer, Germany, in 1867, it dates from 350 AD, making it a venerable vintage indeed, but one recently outdone by a bottle first discovered five years ago in Carmona, near Seville, Spain. “At the bottom of a shaft found during construction work,” an excavation team “uncovered a sealed burial chamber from the early first century C.E. — untouched for 2,000 years,” writes Scientific American’s Lars Fischer. Inside was “a glass urn placed in a lead case was filled to the brim with a reddish liquid,” only recently determined to be wine — and therefore wine about three centuries older than the Speyer bottle.

You can read about the relevant research in this new paper published in the Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports by chemist José Rafael Ruiz Arrebola and his team. “The wine from the Carmona site was no longer suitable for drinking, and it had never been intended for that purpose,” writes Fischer.

“The experts found bone remains and a gold ring at the bottom of the glass vessel. The burial chamber was the final resting place for the remains of the deceased, who were cremated according to Roman custom.” Only through chemical analysis were the researchers finally able to determine that the liquid was, in fact, wine, and thus to put together evidence of the arrangement’s being an elaborate sendoff for a Roman-era oenophile.

Though the funerary ritual “involved two men and two women,” says CBS News, the remains in the wine came from only one of the men. This makes sense, as, “according to the study, women in ancient Rome were prohibited from drinking wine.” What a difference a couple of millennia make: today the cultural image slants somewhat female, especially in the case of white wine, which, despite having “acquired a reddish hue,” the liquid unearthed in Carmona was chemically determined to be. With the summer now getting into full swing, this story might inspire us to beat the heat by putting a bottle of our favorite Chardonnay, Riesling, or Pinot Grigio in the refrigerator — a convenience unimagined by even the wealthiest wine-loving citizens of the Roman Empire.

Related content:

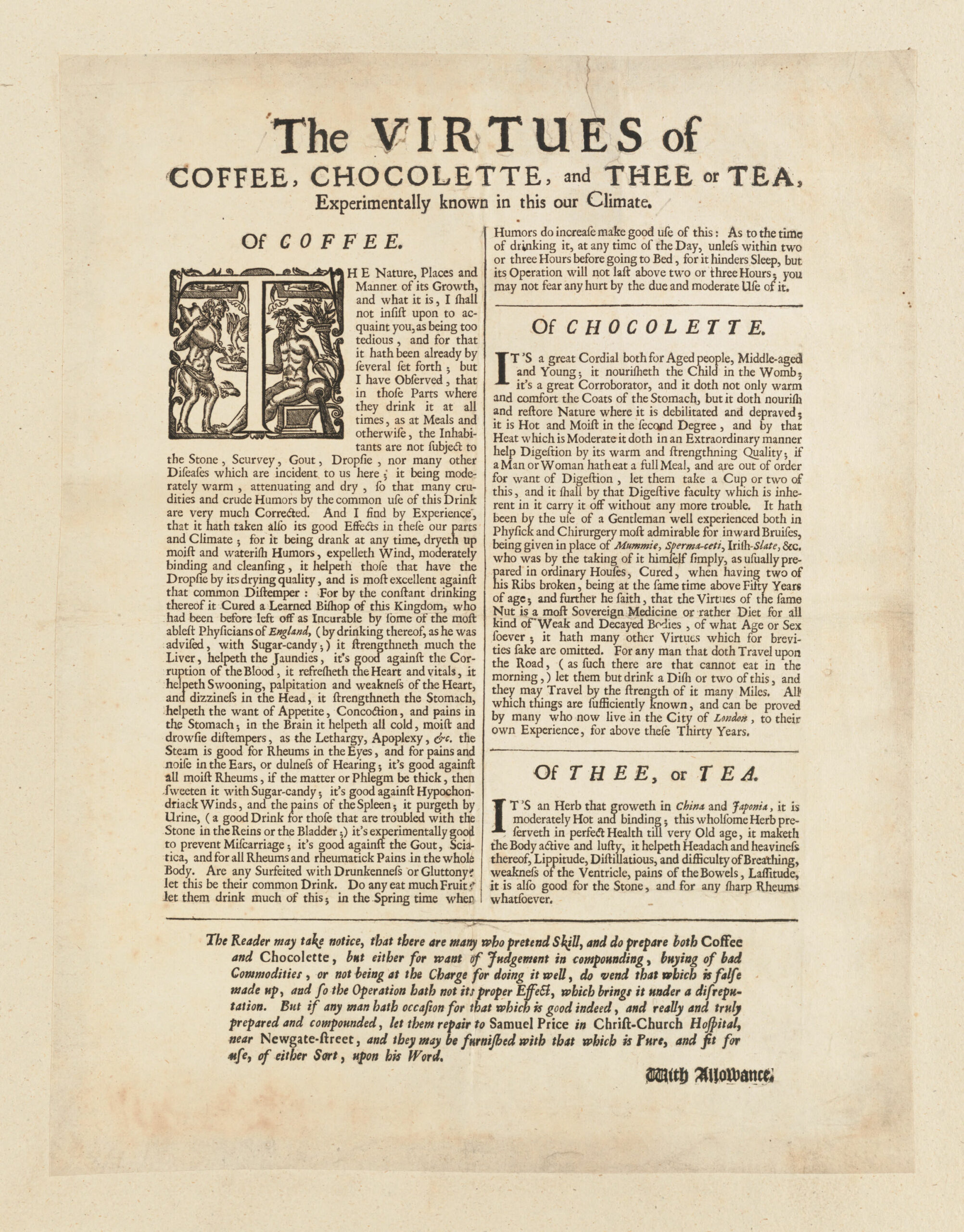

Bars, Beer & Wine in Ancient Rome: An Introduction to Roman Nightlife and Spirits

Archaeologists Discover a 2,000-Year-Old Roman Glass Bowl in Perfect Condition

Archaeologists Discover an Ancient Roman Snack Bar in the Ruins of Pompeii

Explore the Roman Cookbook, De Re Coquinaria, the Oldest Known Cookbook in Existence

The Wine Windows of Renaissance Florence Dispense Wine Safely Again During COVID-19

The Oldest Unopened Bottle of Wine in the World (Circa 350 AD)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities and the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.