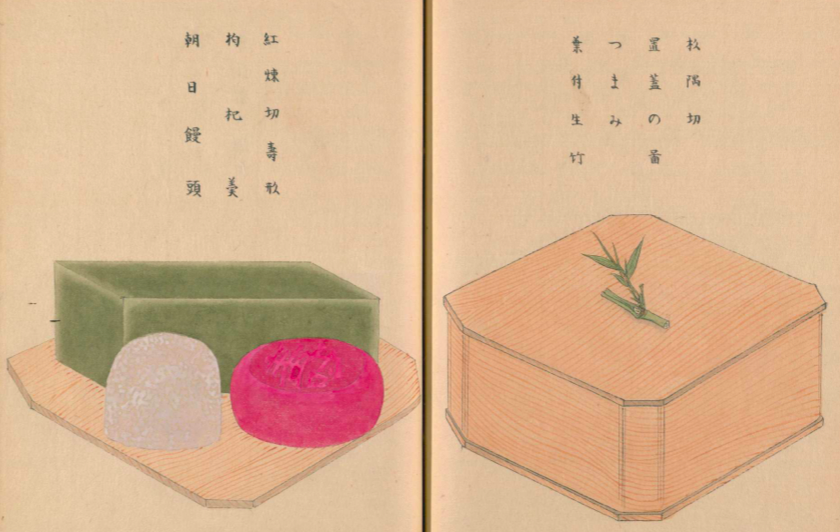

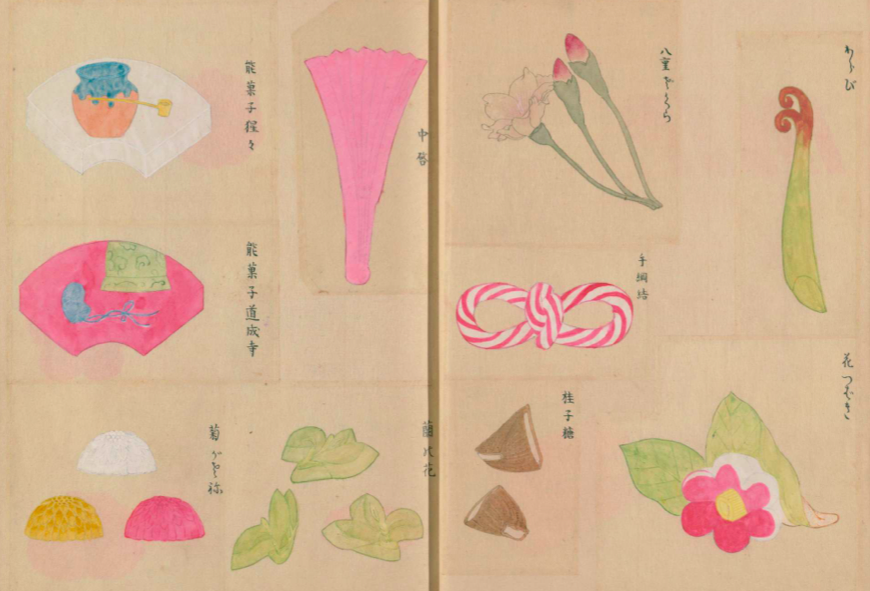

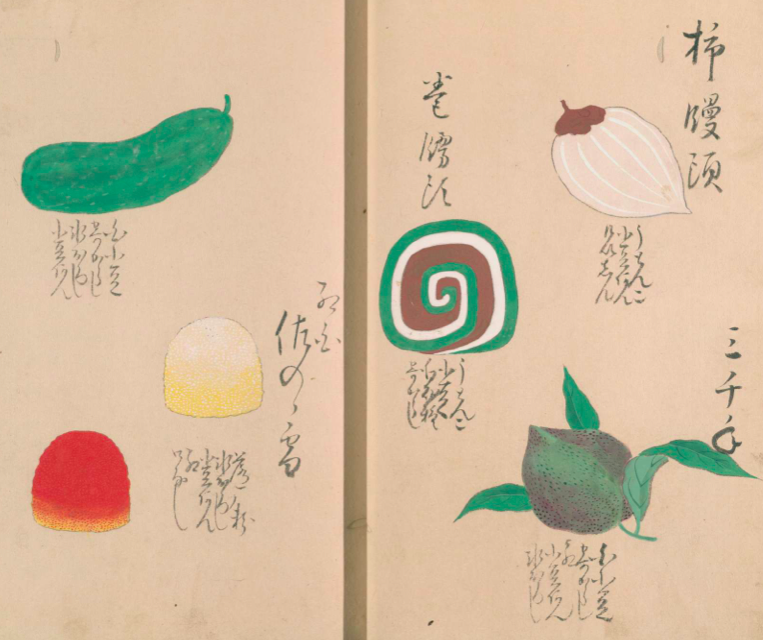

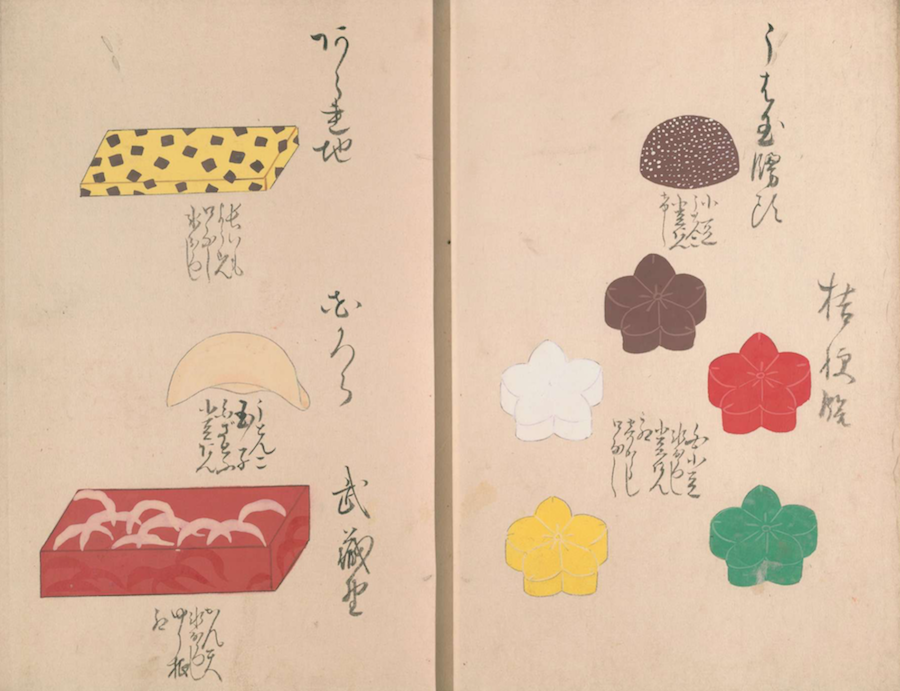

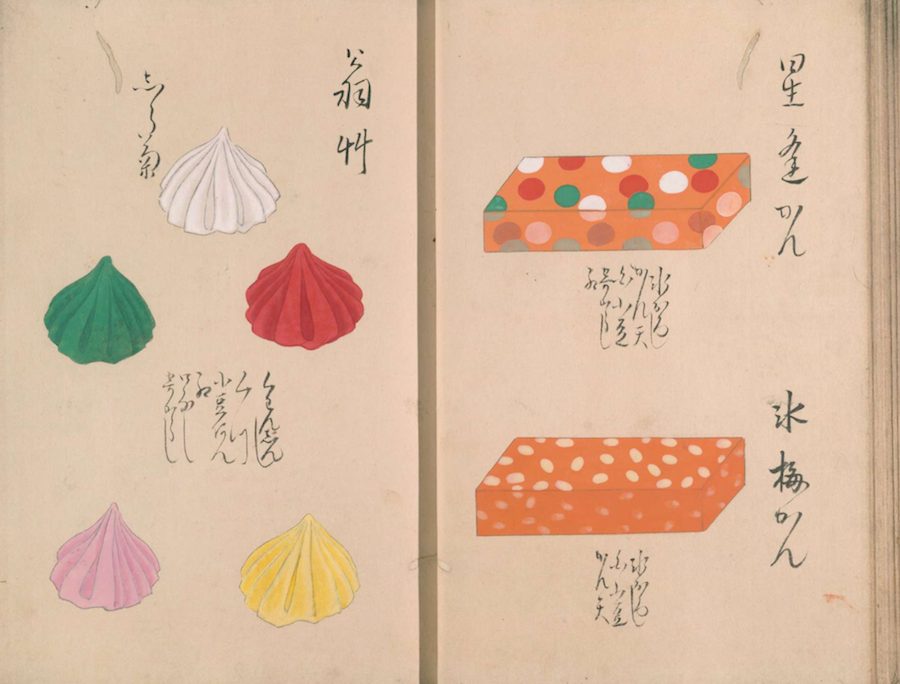

If you’ve been to Japan, or even to any of the Japanese neighborhoods in cities around the world, you’ve seen wagashi (和菓子). You’ve probably, at least for a moment, marveled at their appearance as well: though essentially nothing more than sweet treats, they’re made with such striking variety and refinement that you might hesitate to bite into them.

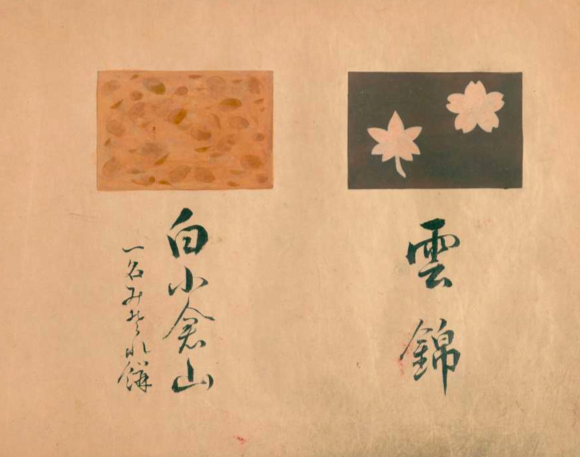

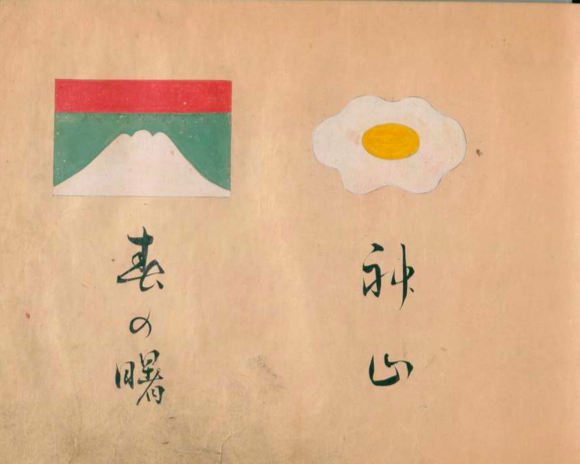

First created in the 16th century, when trade with China made sugar into a staple in Japan, wagashi have developed into one of the country’s signature delicacies, appreciated for their taste but beloved for their form. You can browse and download a three-volume catalog of wagashi designs, itself centuries old, at the web site of Japan’s National Diet Library: volume one, volume two, volume three.

The site also has a special section about wagashi, though in Japanese only. The catalog itself, of course, also contains text in no other language, but wagashi isn’t about words.

Even without knowing Japanese, you can flip through each volume’s pages (volume one — volume two - volume three) and recognize the look of dozens of sweets you’ve seen or maybe even sampled in real life, where their colors may well look even more vivid than on the page.

Like most realms of traditional Japanese culture, wagashi demands painstaking craftsmanship. Often brought out at festivals and given as gifts, it also celebrates different aspects of Japan: its seasons, its landscapes, chapters of its history, and even its works of literature. Some wagashi designs do this abstractly, while others lean toward the representative, replicating real sights and symbols in a form both recognizable and edible.

Many wagashi, as Boing Boing’s Andrea James writes, “still look the same as they did hundreds of years ago when the art form flourished in the Edo period” of the 17th and 18th century. Instagram, as she points out, has proven a natural online home for not just the kind of traditional wagashi seen in these catalogs but designs that pay tribute to figures of more recent vintage, such as Rilakkuma and the aliens from Toy Story.

And though Halloween may not be an originally Japanese holiday, it hasn’t stopped modern wagashi-makers from bringing out the ghosts, skulls, and jack-o-lanterns in force.

via BoingBoing

Related Content:

Download Classic Japanese Wave and Ripple Designs: A Go-to Guide for Japanese Artists from 1903

How Japanese Things Are Made in 309 Videos: Bamboo Tea Whisks, Hina Dolls, Steel Balls & More

20 Mesmerizing Videos of Japanese Artisans Creating Traditional Handicrafts

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.