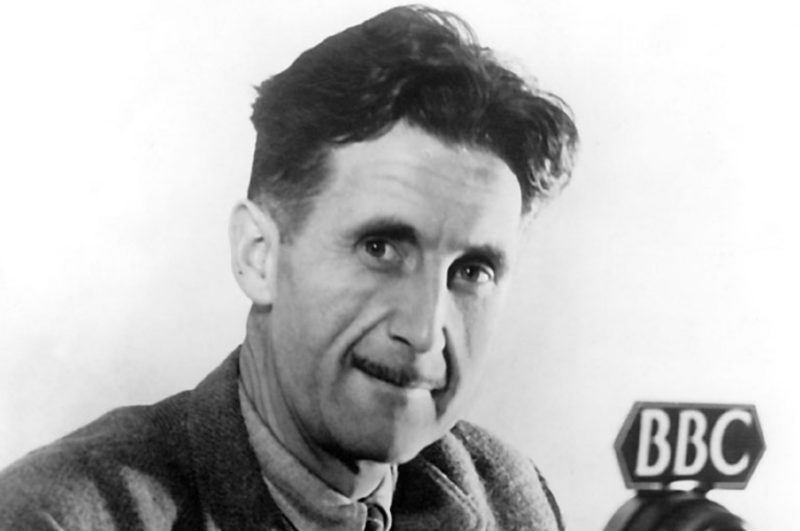

Image by BBC, via Wikimedia Commons

Voltaire once joked that Britain had “a hundred religions and only one sauce.” In my experience, that sauce is a curry, which was already a British staple in Voltaire’s time. No doubt he had something much blander in mind. Of course, it’s all hyperbolic fun until someone takes offense, as did George Orwell in 1946, when he wrote, against Voltairean stereotypes, about the misunderstood pleasures of British food. His essay, “British Cookery,” was commissioned by the British Council, but they subsequently deemed that it would be “’unwise to publish,’” reports the Daily Mail, “so soon after the hungry winter of 1946 and wartime rationing.”

Not that it matters much now, but the Council has formally apologized to the deceased Orwell, over 70 years later. Senior policy analyst Alasdair Donaldson explains they are “delighted to make amends” by publishing the essay in full, alongside “the unfortunate rejection letter.” You can read it here at the British Council site. Orwell grants that the British diet is “simple, rather heavy, perhaps slightly barbarous… with its main emphasis on sugar and animal fats…. Cheap restaurants in Britain are almost invariably bad, while in expensive restaurants the cookery is almost always French, or imitation French.”

Elsewhere, he concedes, “the British are not great eaters of salads.” Indeed, he says, “the two great shortcomings of British cookery are a failure to treat vegetables with due seriousness, and an excessive use of sugar.” He does go on at length, in fact, about what sounds like a national epidemic of sugar addiction. Such lapses of taste are also what we would now label a nutritional emergency. He may seem to grant too much to critics of British cooking. But this is mainly by contrast with spicier, more vegetable-friendly cuisines of the continent and colonies. The kind of cooking he describes makes creatively varied uses of sturdy but limited local resources (except for the sugar).

Orwell’s brutal honesty about British food’s deficiencies makes him sound like a trustworthy guide to its true delights. One of the truths he tells is that “British cookery displays more variety and more originality than foreign visitors are usually ready to allow.” The average visitor encounters British food principally in restaurants, pubs, and hotels, which, “whether cheap or expensive” are not representative of “the diet of the great mass of the people.” This may be said of many regional cuisines. But Orwell is devoted to a native British cooking which had, at the time, almost disappeared after six years of war rationing.

This cooking is rich in roast and cold meats, cheeses, breads, Yorkshire and suet puddings, potatoes and turnips. The British diet is, or was, Orwell writes, eaten by the lower and upper classes alike, under different names and prices. Seasonings are few. “Garlic, for instance, is unknown in British cookery proper.” What stands out is mint, vinegar, butter, dried fruits, jam, and marmalade.

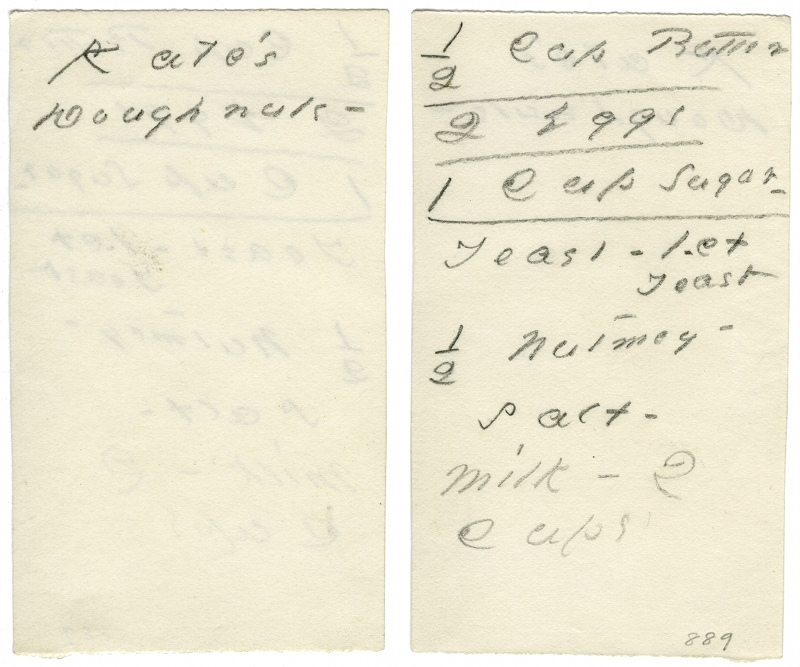

Orwell himself included a marmalade recipe. (A handwritten note reads “Bad recipe! Too much sugar and water.”), which you can see below. Decide for yourself how much sugar to add.

ORANGE MARMALADE

Ingredients:

2 seville oranges

2 sweet oranges (no)

2 lemons (no)

8lbs of preserving sugar

8 pints of water

Method. Wash and dry the fruit. Halve them and squeeze out the juice. Remove some of the pith, then shred the fruit finely. Tie the pips in a muslin bag. Put the strained juice, rind and pips into the water and soak for 48 hours. Place in a large pan and simmer for 1/2 hours until the rind is tender. Leave to stand overnight, then add the sugar and let it dissolve before bringing to the boil. Boil rapidly until a little of the mixture will set into a jelly when placed on a cold plate. Pour into jars which have been heated beforehand, and cover with paper covers.

An increasing number of people are cutting back or quitting nearly every main ingredient in what Orwell describes as authentic British cooking: from meat to dairy to gluten to sugar to suet…. But if we are going to give it a fair shake, he argues, we must try the real thing. Or his version of it anyway. He includes several more recipes: Welsh rarebit, Yorkshire pudding, treacle tart, plum cake, and Christmas pudding.

Orwell’s “British Cookery” wars with itself and comes to terms. He fills each paragraph with frank acknowledgements of British cuisine’s shortcomings, yet he relishes its simple, solid virtues. He writes that “British cookery” is “best studied in private houses, and more particularly in the homes of the middle-class and working-class masses who have not become Europeanized in their tastes.” It’s a kind of cultural nationalism, but perhaps one suggesting those who want others to understand and appreciate a specific kind British culture should invite outsiders in to share a meal.

Related Content:

George Orwell Explains How to Make a Proper Cup of Tea

Try George Orwell’s Recipe for Christmas Pudding, from His Essay “British Cookery” (1945)

Foodie Alert: New York Public Library Presents an Archive of 17,000 Restaurant Menus (1851–2008)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness