Everything old is new again and Tuscany’s buchette del vino—wine windows—are definitely rolling with the times.

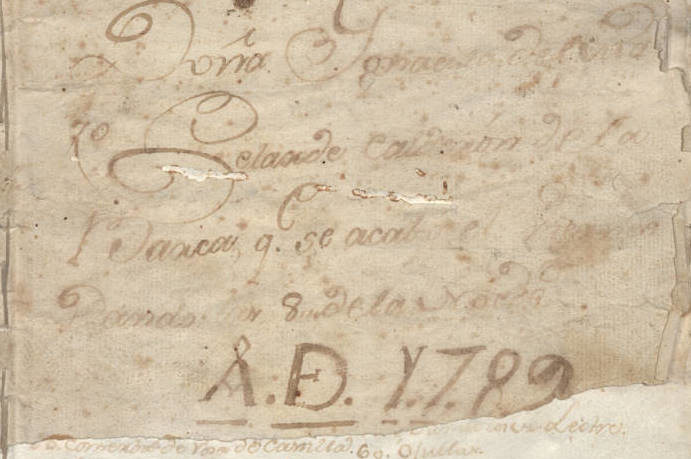

As Lisa Harvey earlier reported in Atlas Obscura, buchette del vino became a thing in 1559, shortly after Cosimo I de’ Medici decreed that Florence-dwelling vineyard owners could bypass taverns and wine merchants to sell their product directly to the public. Wealthy wine families eager to pay less in taxes quickly figured out a workaround that would allow them to take advantage of the edict without requiring them to actually open their palace doors to the rabble:

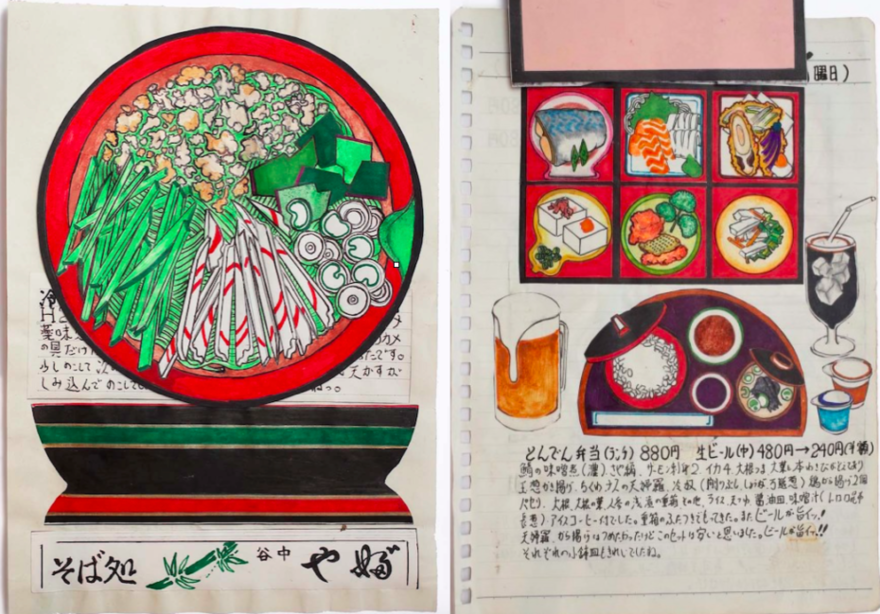

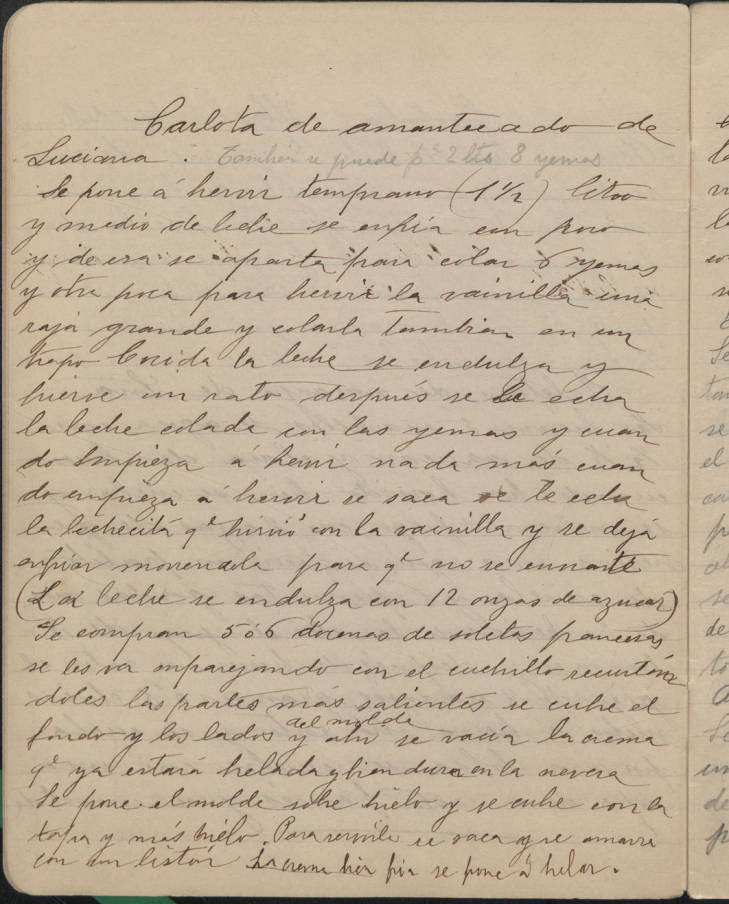

Anyone on the street could use the wooden or metal knocker … and rap on a wine window during its open hours. A well-respected, well-paid servant, called a cantiniere and trained in properly preserving wine, stood on the other side. The cantiniere would open the little door, take the customer’s empty straw-bottomed flask and their payment, refill the bottle down in the cantina (wine cellar), and hand it back out to the customer on the street.

Seventy years further on, these literal holes-in-the-walls served as a means of contactless delivery for post-Renaissance Italians in need of a drink as the second plague pandemic raged.

Scholar Francesco Rondinelli (1589–1665) detailed some of the extra sanitation measures put in place in the early 1630s:

A metal payment collection scoop replaced hand-to-hand exchange

Immediate vinegar disinfection of all collected coins

No exchange of empty flasks brought from home

Customers who insisted on bringing their own reusable bottles could do self-serve refills via a metal tube, to protect the essential worker on the other side of the window.

Sound familiar?

After centuries of use, the windows died out, falling victim to flood, WWII bombings, family relocations, and architectural renovation.

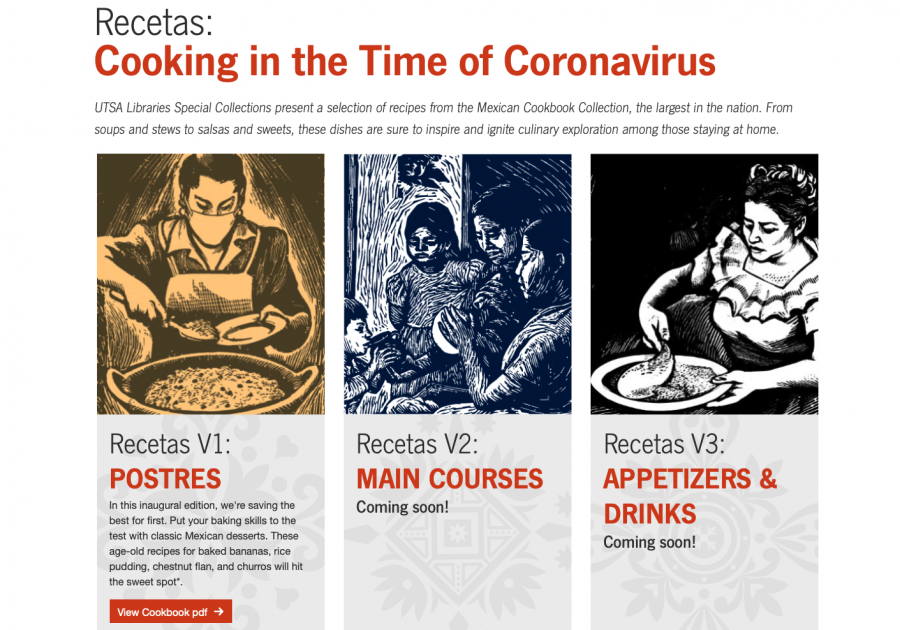

The novel coronavirus pandemic has definitely played a major role in putting wine windows back on the public’s radar, but Babae, a casual year-old restaurant gets credit for being the first to reactivate a disused buchetta del vino for its intended purpose, selling glasses of red for a single hour each day starting in August 2019.

Now several other authentic buchette have returned to service, with menus expanded to accommodate servings of ice cream and coffee.

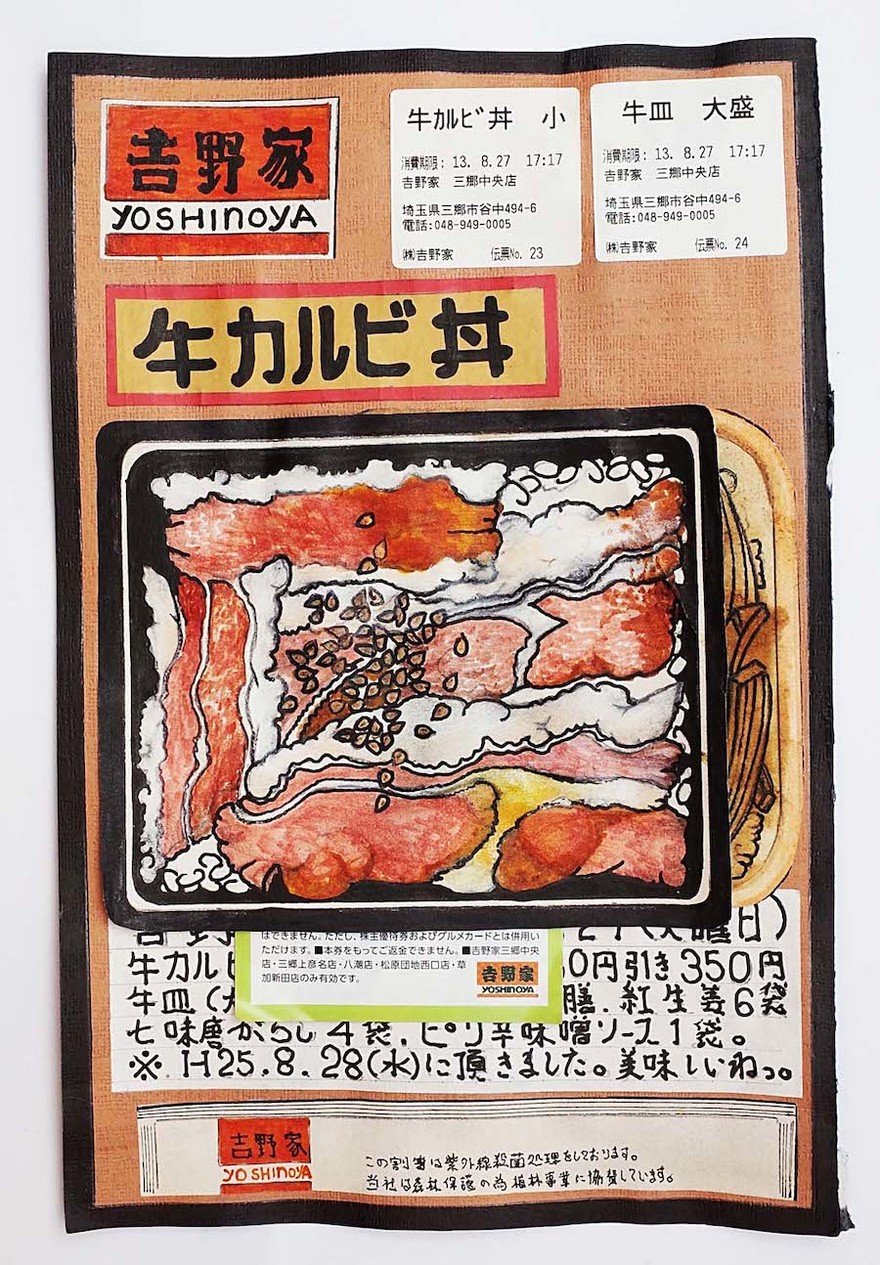

Given this success, perhaps they’ll take a cue from Japan’s 4.6 million vending machines, and begin dispensing an even wider array of items.

They may even take a page from the past, and send some of the money they take in back out, along with food and yes—wine—to sustain needy members of the community.

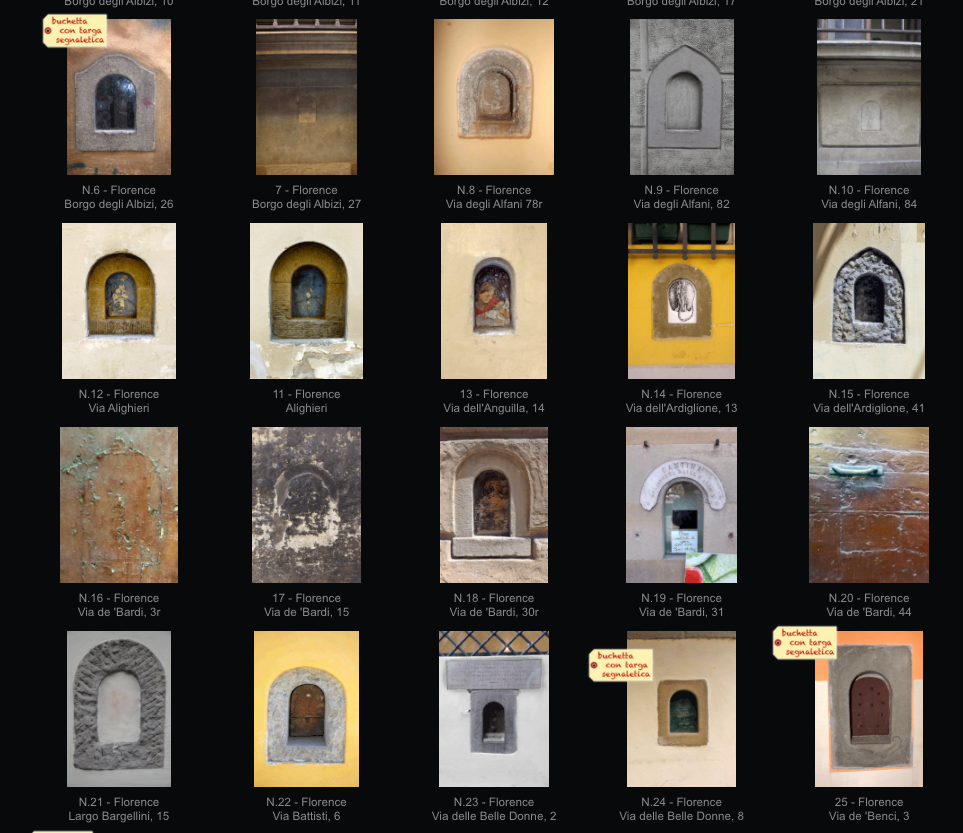

The Buchette del Vino Associazi Culturale currently lists 146 active and inactive wine windows in Florence and the surrounding regions, accompanying their findings with photos and articles of historical relevance.

Via Atlas Obscura

Related Content:

Quarantined Italians Send a Message to Themselves 10 Days Ago: What They Wish They Knew Then

A Free Course from MIT Teaches You How to Speak Italian & Cook Italian Food All at Once

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.