What shall we read before bed?

Georgia O’Keeffe was a fan of cookbooks, telling her young assistant Margaret Wood that they were “enjoyable nighttime company, providing brief and pleasant reading.”

Among the culinary volumes in her Abiquiu, New Mexico ranch home were The Fanny Farmer Boston Cooking School Cookbook, The Joy of Cooking, Let’s Eat Right to Keep Fit and Cook Right, Live Longer.

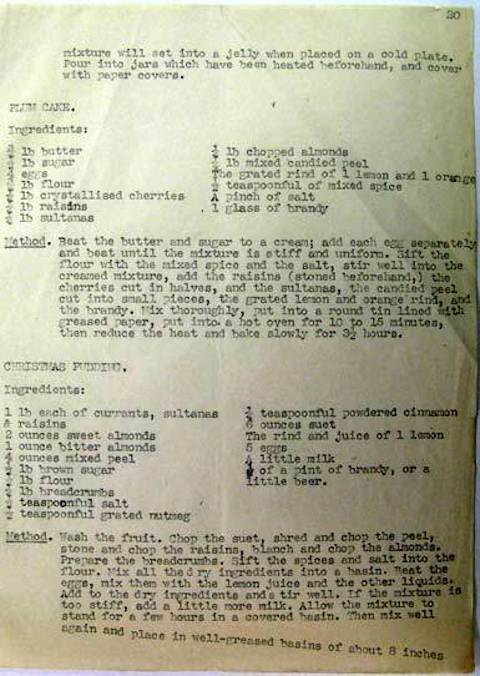

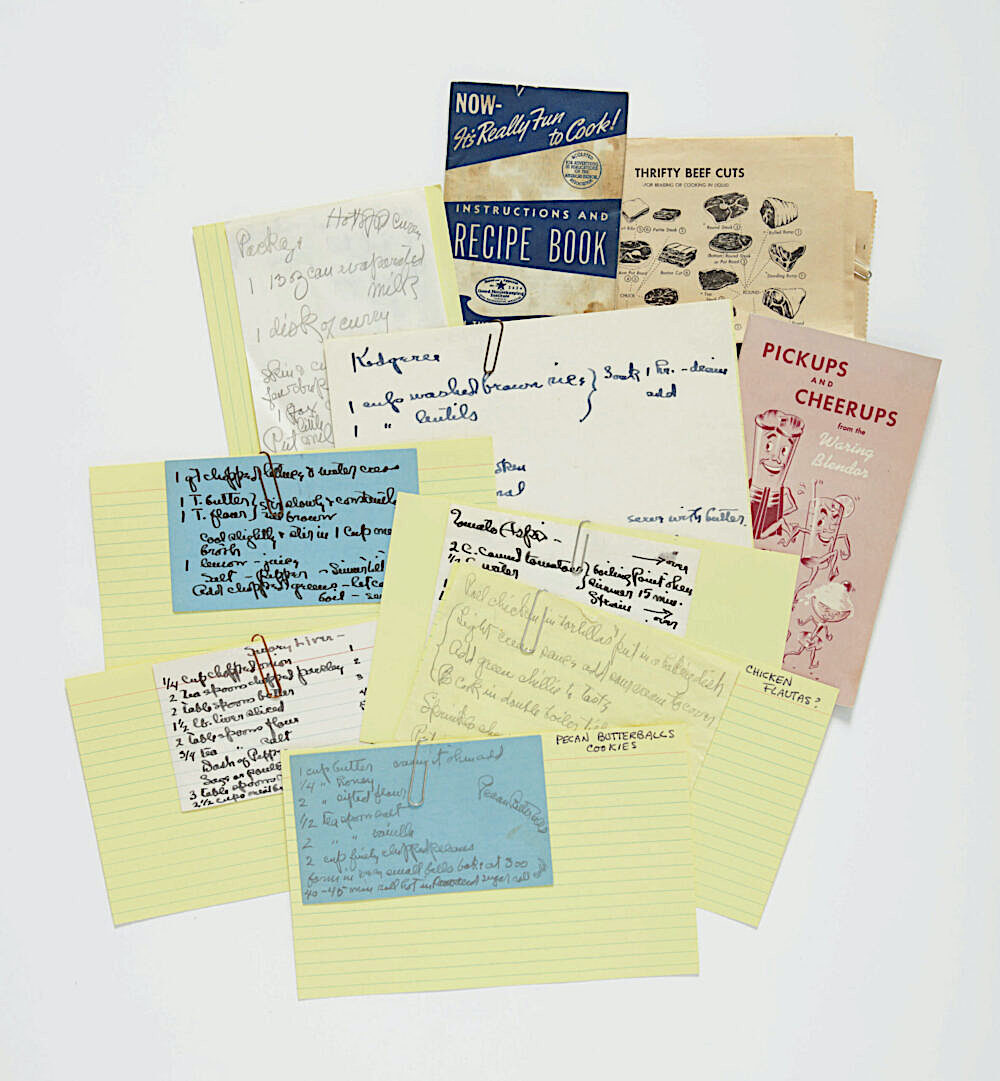

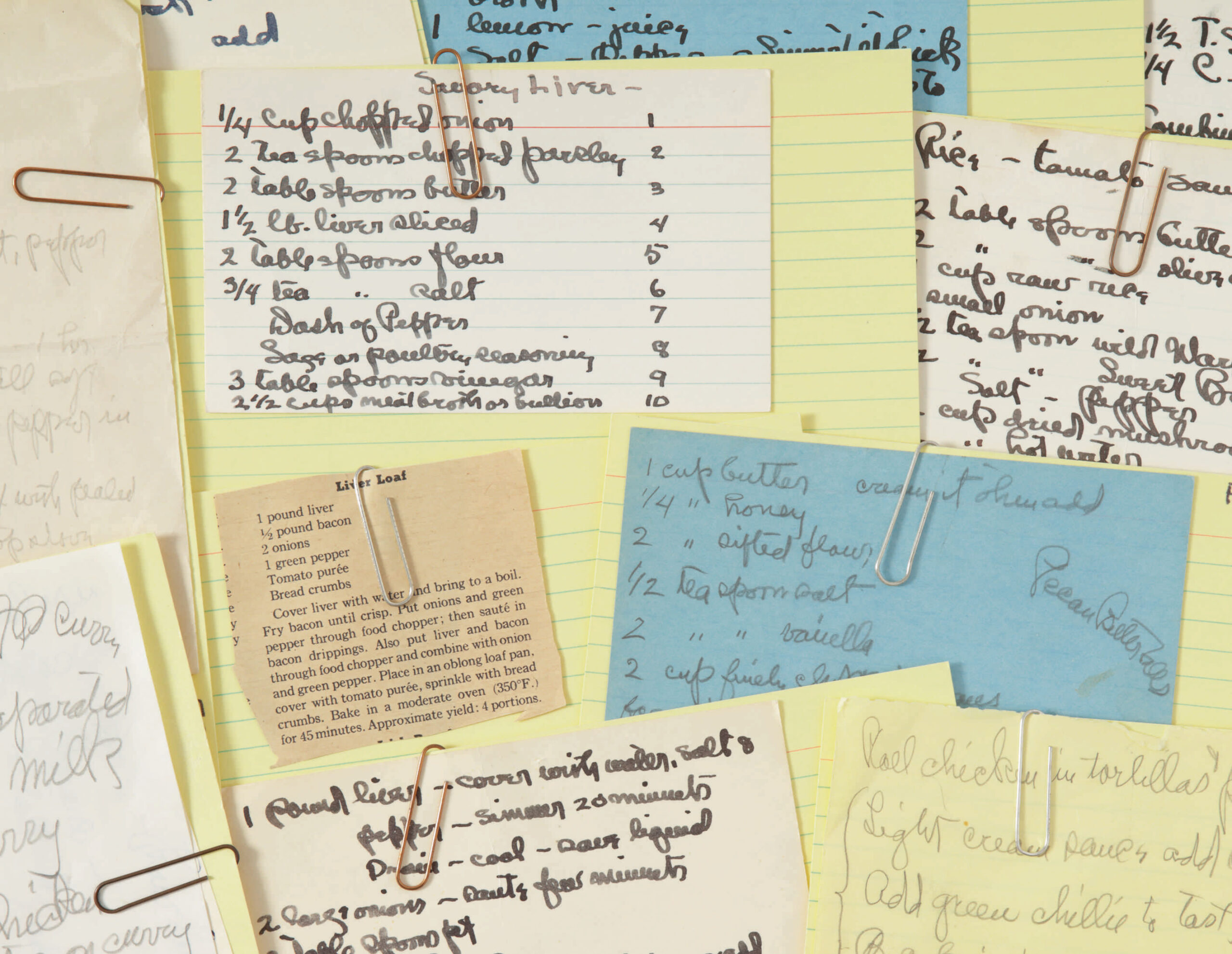

Also Pickups and Cheerups from the Waring Blender, a 21-page pamphlet featuring blended cocktails, that now rests in Yale University’s Beinecke Library, along with the rest of the contents of O’Keeffe’s recipe box, acquired the night before it was due to be auctioned at Sotheby’s. (Some of the images on this page come courtesy of Sotheby’s.)

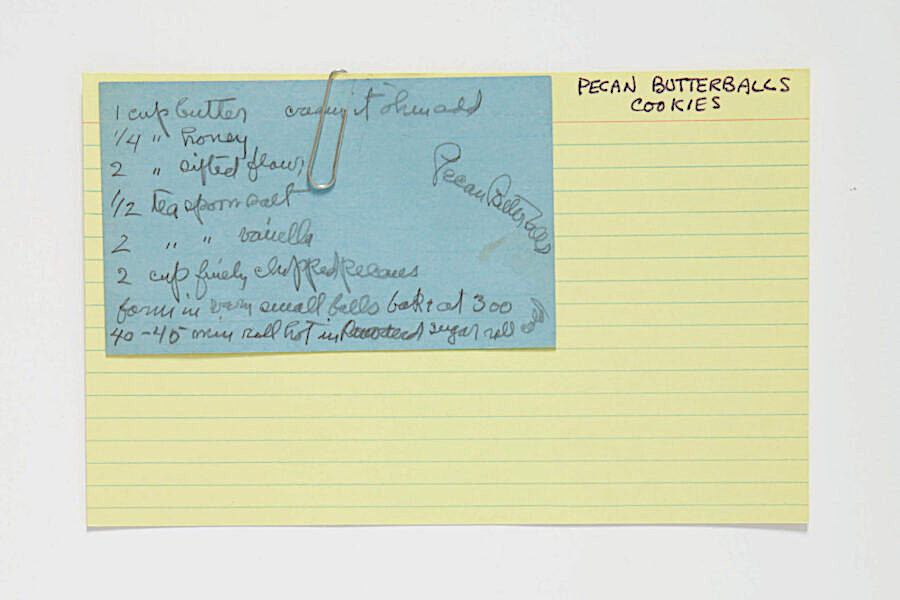

In addition to recipes—inscribed by the artist’s own hand in ink from a fountain pen, typed by assistants, clipped from magazines and newspapers, or in promotional booklets such as the one published by the Waring Products Company—the box housed manuals for O’Keeffe’s kitchen appliances.

The booklet that came with her pressure cooker includes a spattered page devoted to cooking fresh veggies, a testament to her abiding interest in eating healthfully.

O’Keeffe had a high regard for salads, garden fresh herbs, and simple, locally sourced food.

Today’s buddha bowl craze is, however, “the opposite of what she would enjoy” according to Wood, author of the books Remembering Miss O’Keeffe: Stories from Abiquiu and A Painter’s Kitchen: Recipes from the Kitchen of Georgia O’Keeffe.

Wood, who was some 66 years younger than her employer, recently visited The Sporkful podcast to recall her first days on the job :

…she said, “Do you like to cook?”

And I said, “Yes, I certainly do.”

So she said, “Well, let’s give it a try.”

And after two days of my hippie health food, she said, “My dear, let me show you how I like my food.” My first way of trying to cook for us was a lot of brown rice and chopped vegetables with chicken added. And that was not what she liked.

An example of what she did like: Roasted lemon chicken with fried potatoes, a green salad featuring lettuce and herbs from her garden, and steamed broccoli.

Also yogurt made with the milk of local goats, whole wheat flour ground on the premises, watercress plucked from local streams, and home canning.

Most of these labor-intensive tasks fell to her staff, but she maintained a keen interest in the proceedings.

Not for nothing did the friend who referred Wood for the job warn her it would “require a lot of patience because Miss O’Keeffe was extremely particular.”

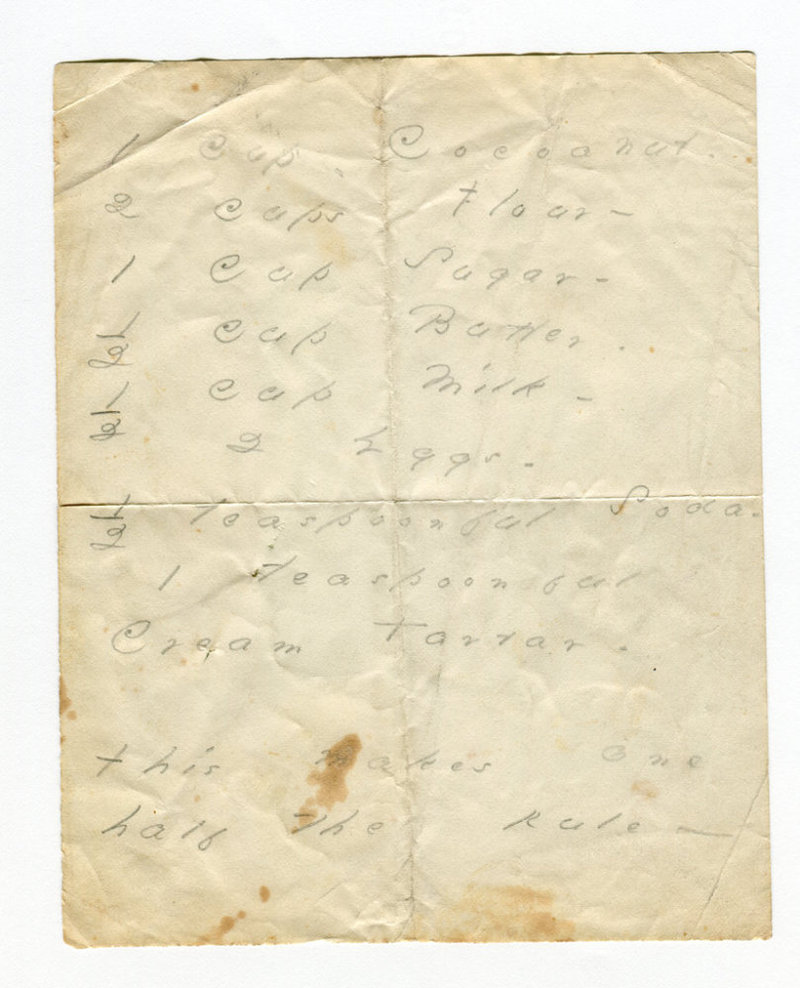

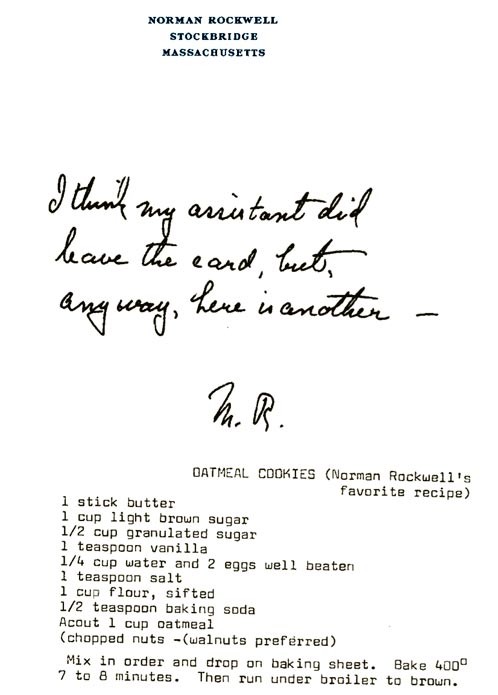

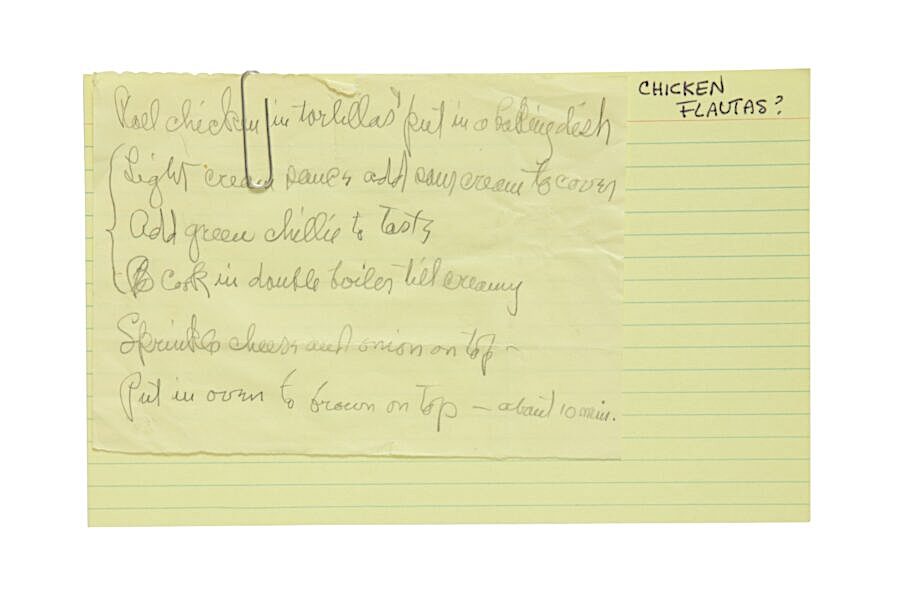

The jottings from the recipe box don’t really convey this exacting nature.

Those accustomed to the extremely specific instructions accompanying even the simplest recipes to be found on the Internet may be shocked by O’Keeffe’s brevity.

Perhaps we should assume that she stationed herself close by the first time any new hire prepared a recipe from one of her cards, knowing she would have to verbally correct and redirect.

(O’Keeffe insisted that Wood stir according to her method—don’t scrape the sides, dig down and lift up.)

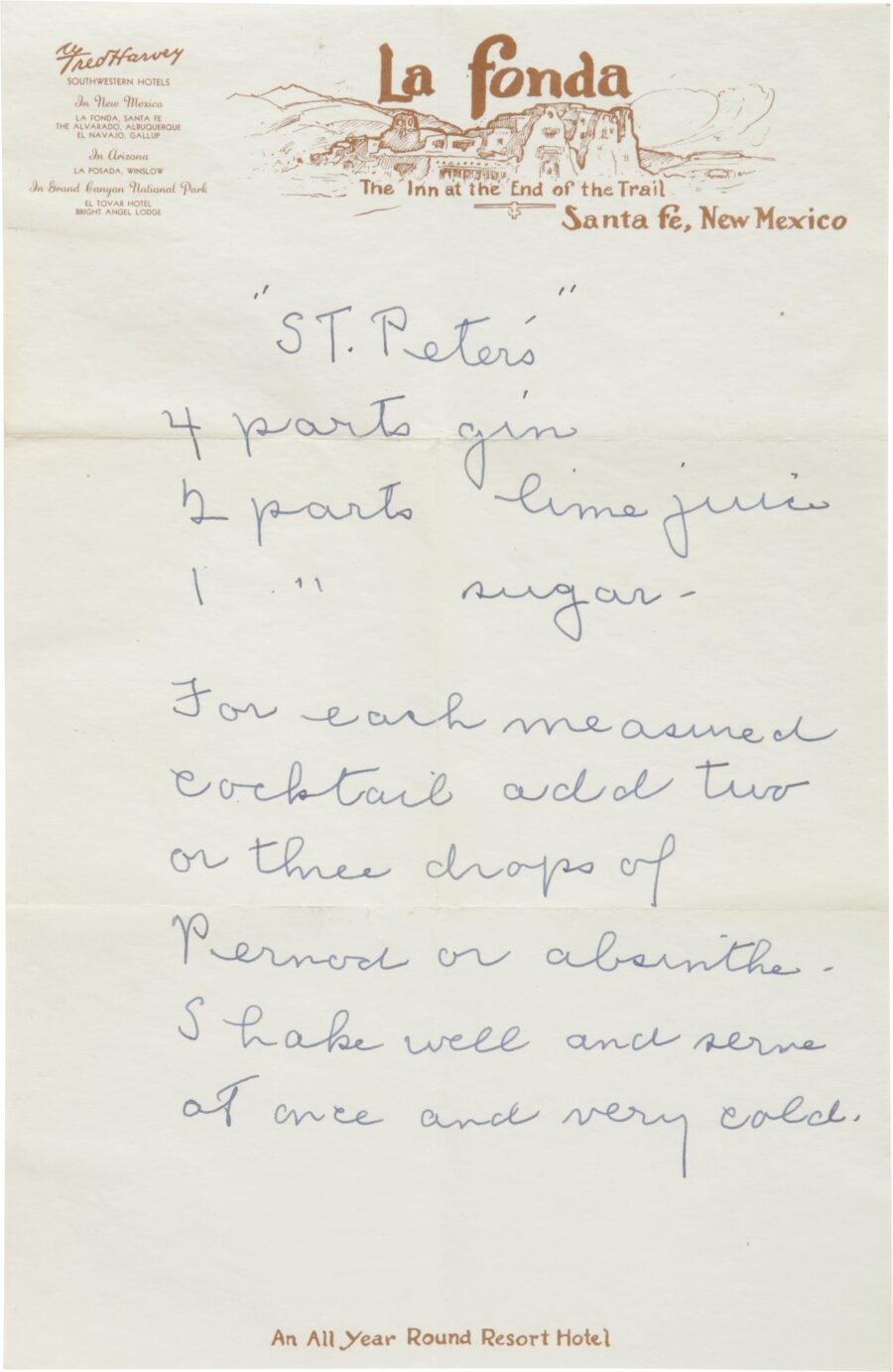

The box also contained recipes that were likely rarities on O’Keeffe’s table, given her dietary preferences, though they are certainly evocative of the period: tomato aspic, Maryland fried chicken, Floating Islands, and a cocktail she may have first sipped in a Santa Fe hotel bar.

The Beinecke plans to digitize its newly acquired collection. This gives us hope that one day, the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum may follow suit with the red recipe binder Wood mentions in A Painter’s Kitchen:

This was affectionately referred to as “Mary’s Book,” named after a previous staff member who had compiled it. That notebook was continually consulted, and revised to include new recipes or to improve on older ones…. As she had collected a number of healthy and flavorful recipes, she would occasionally laugh and comment, “We should write a cookbook.”

Related Content:

Explore 1,100 Works of Art by Georgia O’Keeffe: They’re Now Digitized and Free to View Online

Georgia O’Keeffe: A Life in Art, a Short Documentary on the Painter Narrated by Gene Hackman

The Art & Cooking of Frida Kahlo, Salvador Dali, Georgia O’Keeffe, Vincent Van Gogh & More

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.