The food of our ancestors has come back into fashion, no matter from where your own ancestors in particular happened to hail. Whether motivated by a desire to avoid the supposedly unhealthy ingredients and processes introduced in modernity, a curiosity about the practices of a culture, or simply a spirit of culinary adventure, the consumption of traditional foods has attained a relatively high profile of late. So, indeed, has their preparation: few of us could think of a more traditional food than bread, the home-baking of which became a sweeping fad in the United States and elsewhere shortly after the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Max Miller, for example, has baked more than his own share of bread at home. Like no few media-savvy culinary hobbyists, he’s put the results on Youtube; like those hobbyists who develop an unquenchable thirst for ever-greater depth and breadth (no pun intended) of knowledge about the field, he’s gone well beyond the rudiments.

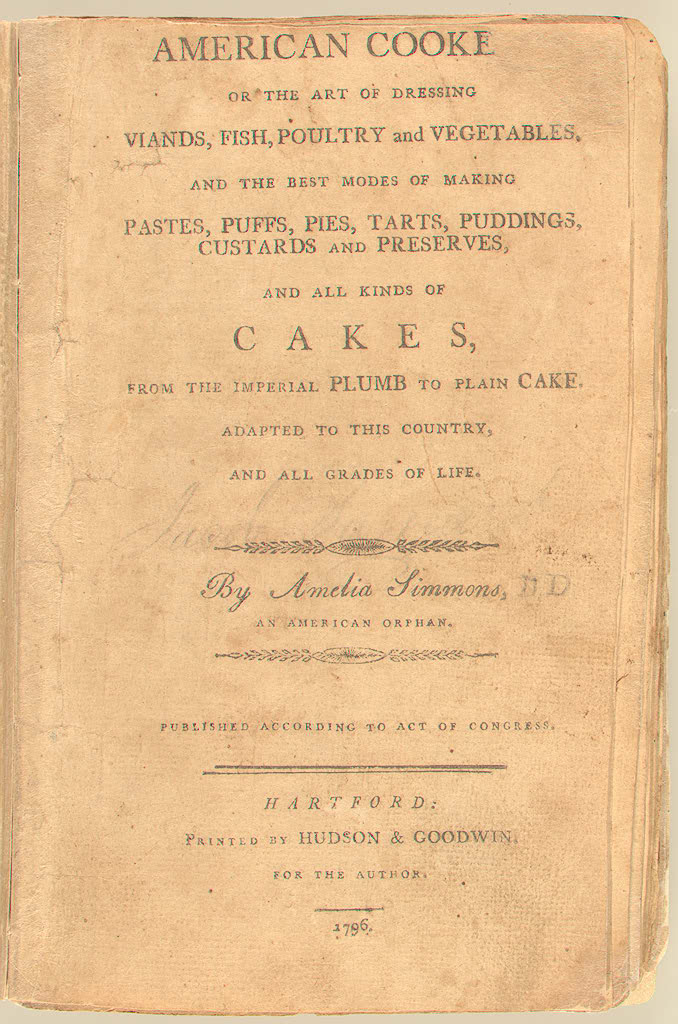

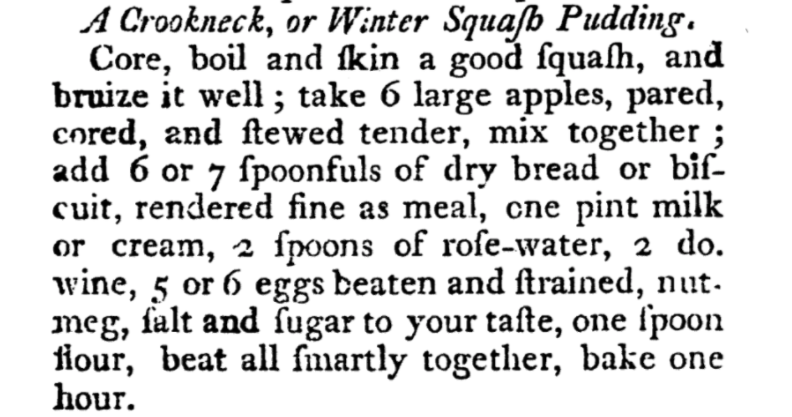

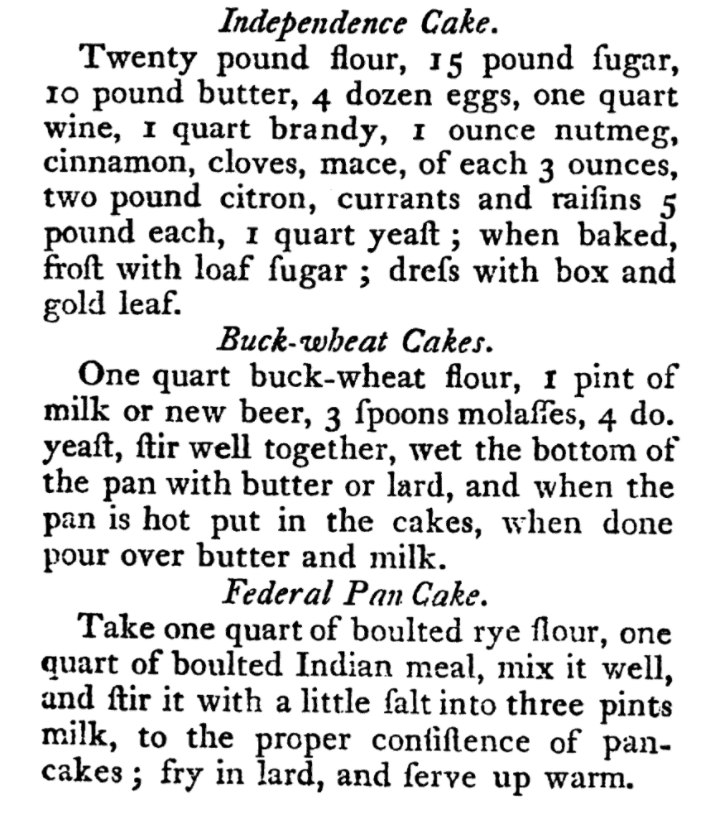

18th-century Saly Lunn buns, medieval trencher, Pompeiian panis quadratus, even the bread of ancient Egypt: he’s gone a long way indeed beyond simple sourdough. But in so doing, he’s learned — and taught — a great deal about the variety of civilizations, all of them heartily food-eating, that led up to ours.

“His show, Tasting History with Max Miller, started in late February,” writes Devan Sauer in a profile last year for the Phoenix New Times. “Since then, Tasting History has drawn more than 470,000 subscribers and 14 million views.” Each of its episodes “has a special segment where Miller explains the history of either the ingredients or the dish’s time period.” These periods come organized into playlists like “Ancient Greek, Roman, & Mesopotamian Recipes,” “The Best of Medieval & Renaissance Recipes,” and “18th/19th Century Recipes.” In his clearly extensive research, “Miller looks to primary accounts, or anecdotal records from the people themselves, rather than historians. He does this so he can get a better glimpse into what life was like during a certain time.”

If past, as L.P. Hartley put it, is a foreign country, then Miller’s historical cookery is a form of not just time travel, but regular travel — exactly what so few of us have been able to do over the past year and a half. And though most of the recipes featured on Tasting History have come from Western, and specifically European cultures, its channel also has a playlist dedicated to non-European foods such as Aztec chocolate; the kingly Indian dessert of payasam; and hwajeon, the Korean “flower pancakes” served in 17th-century snack bars, or eumshik dabang. He’s also prepared the snails served at the thermopolium, the equivalent establishment of the first-century Roman Empire recently featured here on Open Culture. But however impressive Miller’s knowledge, enthusiasm, and skill in the kitchen, he commands just as much respect for having mastered Youtube, the true Forum of early 21st-century civilization.

Related Content:

What Did People Eat in Medieval Times? A Video Series and New Cookbook Explain

Cook Real Recipes from Ancient Rome: Ostrich Ragoût, Roast Wild Boar, Nut Tarts & More

How to Bake Ancient Roman Bread Dating Back to 79 AD: A Video Primer

How to Make the Oldest Recipe in the World: A Recipe for Nettle Pudding Dating Back 6,000 BC

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.