When you watch an animated film, you visit a world. That holds true, to an extent, for live-action movies as well, but much more so for those cinematic experiences whose audiovisual details all come, of necessity, crafted from scratch. Walt Disney understood that better than anyone else in the motion-picture industry, and none could argue that he didn’t capitalize on it. When they founded Studio Ghibli, Hayao Miyazaki and the late Isao Takahata — in the fine 20th-century Japanese tradition of borrowing Western ideas and then refining them nearly beyond recognition — took Disney’s deliberate world-building a step further, painstakingly crafting a look and feel for their productions that amounts to a separate reality: rich, coherent, and, for the millions of die-hard Ghibli fans all around the world, immensely appealing.

In a few years, those fans will get the chance to enter Ghibli’s world in a much more concrete sense. Disney’s insight that his audience would beat a path to an amusement park based on his studio’s movies led to Disneyland, Disney World, and their global successors, two of which, Tokyo Disneyland and Tokyo Disney Sea, now rank among the five most visited theme parks in the world.

The area of the Japanese capital already offers an acclaimed Ghibli experience in the form of the Ghibli Museum, but in just a few years the city of Nagakute, a suburb of Nagoya, will see the opening of Ghibli’s own version of Disneyland, a theme park filled with attractions based on the studios beloved films.

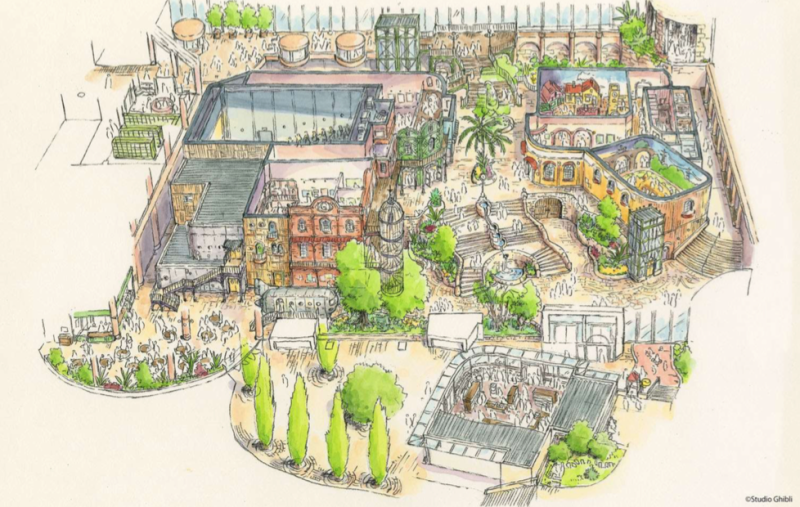

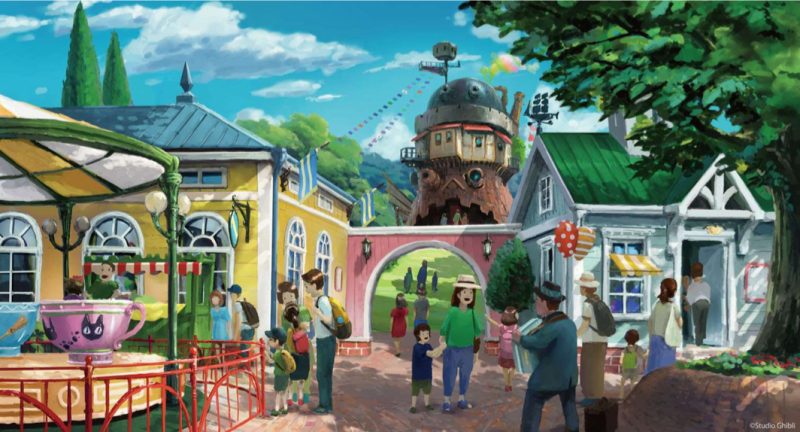

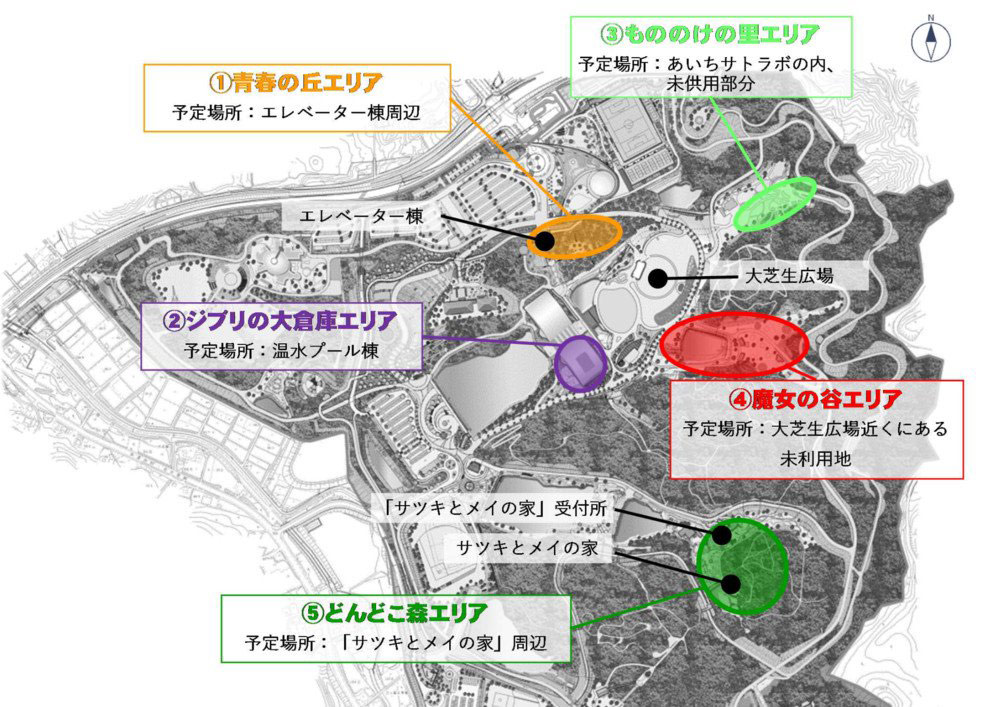

Scheduled to open in 2022 on the same plot of land used for the 2005 World’s Fair (where the house from My Neighbor Totoro was then built and still stands today), Ghibli’s theme park will greet visitors with a main gate reminiscent, writes Kotaku’s Brian Ashcraft, of “19th-century structures out of Howl’s Moving Castle as well as a recreation of Whisper of the Heart’s antique shop.”

It also includes “the Big Ghibli Warehouse, which is filled with all sorts of Ghibli themed play areas as well as exhibition areas and small cinemas,” a Princess Mononoke village, a combined area for Howl’s Moving Castle and Kiki’s Delivery Service called Witch Valley, and the Totoro-themed Dondoko Forest. Will Studio Ghibli’s theme park rise into the ranks of the world’s most visited? Nobody who has yet visited their world, in any of its manifestations thus far, would put it past them.

Studio Ghibli has released some basic concept for the new theme park. You can get a few glimpses of what they have in mind on this page.

Related Content:

How the Films of Hayao Miyazaki Work Their Animated Magic, Explained in 4 Video Essays

What Made Studio Ghibli Animator Isao Takahata (RIP) a Master: Two Video Essays

Watch Hayao Miyazaki’s Beloved Characters Enter the Real World

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.