Public domain fans, pull your noses out of those musty old books on Project Gutenberg, but keep your eyes glued to the screen!

The Library of Congress just cut the ribbon on the National Screening Room, an online trove of cinematic goodies, free for the streaming.

Given that the collection spans more than 100 years of cinema history, from 1890–1999, not all of the featured films are in the public domain, but most are, and those are free to download as well as watch.

Archivist Mike Mashon, who heads the Library’s Moving Image Section, identifies the project’s goal as providing the public with a “broad range of historical and cultural audio-visual materials that will enrich education, scholarship and lifelong learning.”

Can’t argue with that. Those seeking to become better versed in the art of consensual kissing whilst mustachioed will find several valuable takeaways in the above clip.

Personal experience, however, compels me to expand upon Mashon’s stated goal: artists, theatermakers, filmmakers—use those downloadable public domain films in your creative projects! (Properly attributed, of course.)

You can educate yourself about a particular clip’s rights and the general ins and outs of motion picture copyrights by scrolling past the clip’s call number to click on “Rights & Access.”

The Library does emphasize that rights assessment is the individual’s responsibility. Few artists conceive of this as the fun part, but do it, or risk the sort of creative heartbreak animator Nina Paley set herself up for when integrating inadequately checked out vintage recordings into her feature-length Sita Sings the Blues, having “decided (she) was just going to use this music, and let the chips fall where they may.”

A hypothetical example: Liza Minnelli’s 2nd or 3rd birthday party at her godfather Ira Gershwin’s Beverly Hills estate?

It’s adorable to the point of irresistible, but alas “for educational purposes only,” a designation that applies to all the Gershwin home movies.

(Watch em, anyway! You never know when you may be called upon to throw an opulent 1940’s‑style toddler party. Forewarned is forearmed! Instagram’s gonna LOVE you.)

Copyright-wise, a good way to hedge your bets is to look for material filmed before 1922, like The Newlyweds, DW Griffith’s meet-cute silent short, starring America’s Sweetheart, Mary Pickford. Look to the leading ladies of that era, if you want to find some worthy tales (and footage) to shoehorn into your #metoo documentary.

Sounds like you’ve got a lot of research ahead of you, friend. But wait, there’s more!

Recharge your batteries with a visit to Peking’s Forbidden City circa 1903.

Wouldn’t that make a fine backdrop to your band’s next music video!

And dibs on the fabled diving horse of Coney Island, whose feats of derring-do were filmed by Thomas Edison.

I could watch that horse dive all day! And so could the audience of that 8‑hour puppet opera I may wind up writing one of these days. It’s set in Coney Island….

Readers, have a rummage and report back. What’s your favorite find in the National Screening Room? Any plans for future use, real or imaginary? Let us know.

If you’re not immediately inspired, don’t despair. Just check back. New content will be uploaded monthly. There are also plans afoot to create educator lesson plans on historical and social topics documented in the collection. Teachers, imagine what your students might create with this classroom tool.…

Begin your visit to the National Screening Room here.

Related Content:

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More

Download 6600 Free Films from The Prelinger Archives and Use Them However You Like

The Library of Congress Makes 25 Million Records From Its Catalog Free to Download

Library of Congress Releases Audio Archive of Interviews with Rock ‘n’ Roll Icons

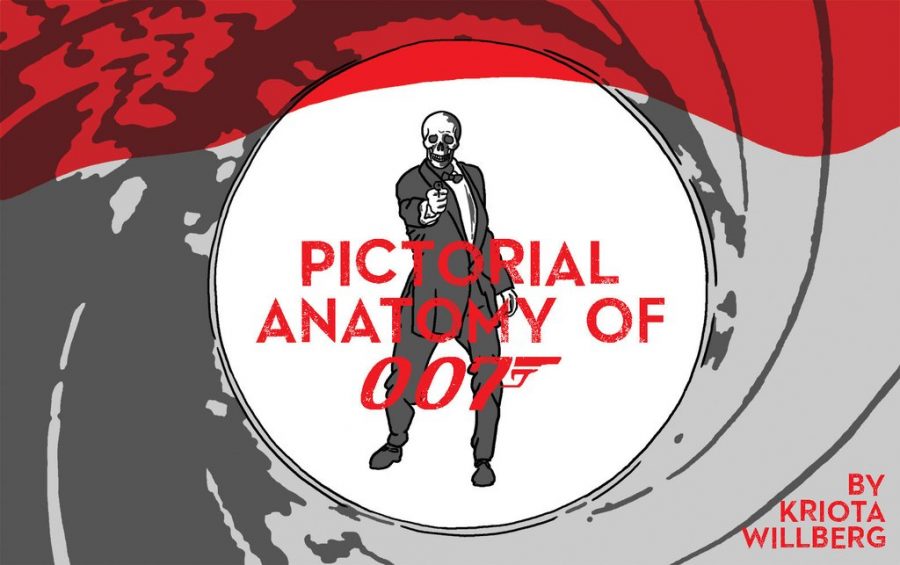

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, October 15 for another monthly installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.