The greatest of the silent clowns is Buster Keaton, not only because of what he did, but because of how he did it. —Roger Ebert

In 1987, Video magazine published a story titled “Where’s Buster?” lamenting the lack of Buster Keaton films available on videotape, “despite renewed interest” in a legend who was “about to regain his rightful place next to Chaplin in silent comedy’s pantheon.” How things have changed for Keaton fans and admirers. Not only are most of the stone-faced comic genius’ films available online, but he has maybe eclipsed Chaplin as the most popularly revered silent film star of the 1920s.

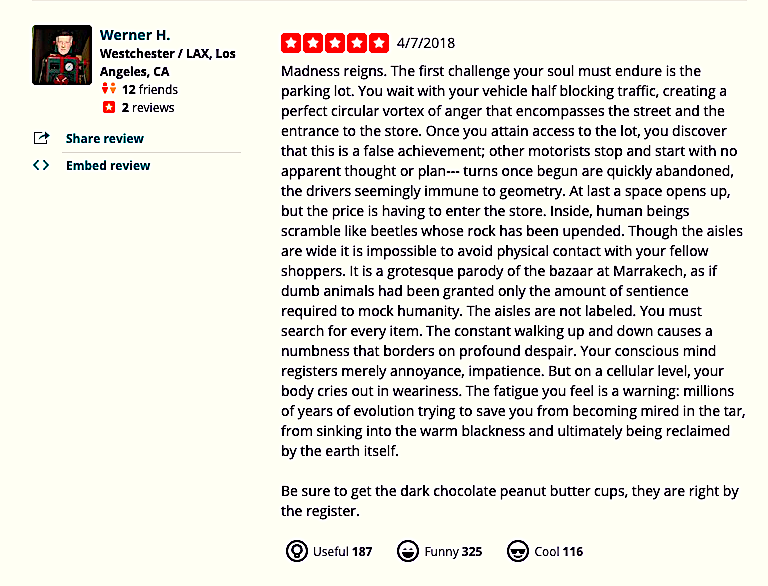

Keaton has always been held in the highest esteem by his fellow artists. He was dubbed “the greatest of all the clowns in the history of the cinema” by Orson Welles, and served as a significant inspiration for Samuel Beckett. (He was the playwright’s first choice to play Waiting for Godot’s Lucky, though he was too perplexed by the script to take the role). In Peter Bogdanovich’s new documentary, The Great Buster: A Celebration, Mel Brooks and Carl Reiner discuss his foundational influence on their comedy, and Werner Herzog calls him “the essence of movies.”

For many years, however, the state of Keaton’s filmography made it hard for the general public to fully appraise his work. “The General, with Buster as a train engineer in the Civil War, has always been available,” Roger Ebert wrote in 2002, and has been “hailed as one of the supreme masterpieces of silent filmmaking. But other features and shorts existed in shabby, incomplete prints, if at all, and it was only in the 1960s that film historians began to assemble and restore Keaton’s lifework. Now almost everything has been recovered, restored, and is available on DVDs and tapes that range from watchable to sparkling.”

Access to Keaton’s films has further expanded as a dozen or so entered the public domain in recent years, including two features, Sherlock, Jr. and The Navigator, this year and three more to come in 2021. You can watch thirty-one of Keaton’s restored, recovered films on YouTube, at the links below, shared by MetaFilter user Going to Maine, who writes, “where, oh where, in this modern world, can we find the gems of his golden era? The obvious place.”

Keaton starred in his first feature-length film, The Saphead, in 1920. For the next decade, until the end of the silent era, he dominated the box office, alongside Chaplin and Harold Lloyd, with his canny blend of daredevil slapstick and everyman pathos. After the twenties, his career floundered, then rebounded. His last picture was a return to silent film in Beckett’s 1966 short, “Film,” made the year of his death. Since then, Keaton appreciation has become almost a form of worship.

In 2018, The General came in at number 34 on Sight & Sound’s Greatest Films of All Time list. But the BFI’s Geoff Andrew argued that it deserved the top spot, and Keaton deserves recognition as “not merely the greatest of the silent comedians,” but “the greatest of all comic actors to have appeared on the silver screen… not only a great American filmmaker of the silent era,” but “one of the greatest filmmakers of all time, anywhere.” Andrew likens him to a god, but “unlike gods… Buster has the advantage of being able to make us laugh. And laugh. And laugh.”

Don’t we all need a steady supply of that medicine these days? See Keaton’s classic silent comedy The General further up and watch 29 more Keaton films at the links below. Many will be added to our collection, 4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & More.

Short Films

One Week (September 1, 1920)

Convict 13 (October 27, 1920)

Neighbors (December 22, 1920)

The Scarecrow (December 22, 1920)

The Haunted House (February 10, 1921)

Hard Luck (March 14, 1921)

The High Sign (April 12, 1921)

The Goat (May 18, 1921)

The Playhouse (October 6, 1921) (This contains a faux minstrel show segment with blackface.)

The Boat (November 10, 1921)

The Paleface (January, 1922) (Racist depictions of Native Americans)

Cops (March, 1922)

My Wife’s Relations (May, 1922)

The Blacksmith (July 21, 1922)

The Frozen North (August 28, 1922)

The Electric House (October, 1922)

Day Dreams (November, 1922)

The Balloonatic (January 22, 1923)

The Love Nest (March, 1923)Features

Three Ages (September 24, 1923)

Our Hospitality (November 19, 1923)

Sherlock Jr. (May 11, 1924)

The Navigator (October 13, 1924)

Seven Chances (March 15, 1925)

Go West (November 1, 1925)

Battling Butler (September 19, 1926)

The General (December 31, 1926)

College (November 1927)

Steamboat Bill, Jr. (May 20, 1928)Bonus! Two of Keaton’s Last Films

The Railrodder, for the National Film Board of Canada (October 2, 1965)

Film, directed by Samuel Beckett (January 8, 1965)

Related Content:

A Supercut of Buster Keaton’s Most Amazing Stunts

Buster Keaton: The Wonderful Gags of the Founding Father of Visual Comedy

List of Great Public Domain Films

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness