Denis Villeneuve’s new adaptation of Frank Herbert’s Dune has made a decently promising start to what looks set to shape up into an epic series of films. But however many installments it finally comprises, it’s unlikely to run anywhere near as long as Alejandro Jodorowsky’s version — had Jodorowsky actually made his version, that is. Previously featured here on Open Culture, that project promised to unite the talents of not just the creator of the Dune universe and the director of The Holy Mountain, but those of Mœbius, H.R. Giger, Salvador Dalí, Pink Floyd, Orson Welles, and Mick Jagger. Even David Lynch’s Dune, for all its large-scale weirdness, would surely play like My Dinner with Andre by comparison.

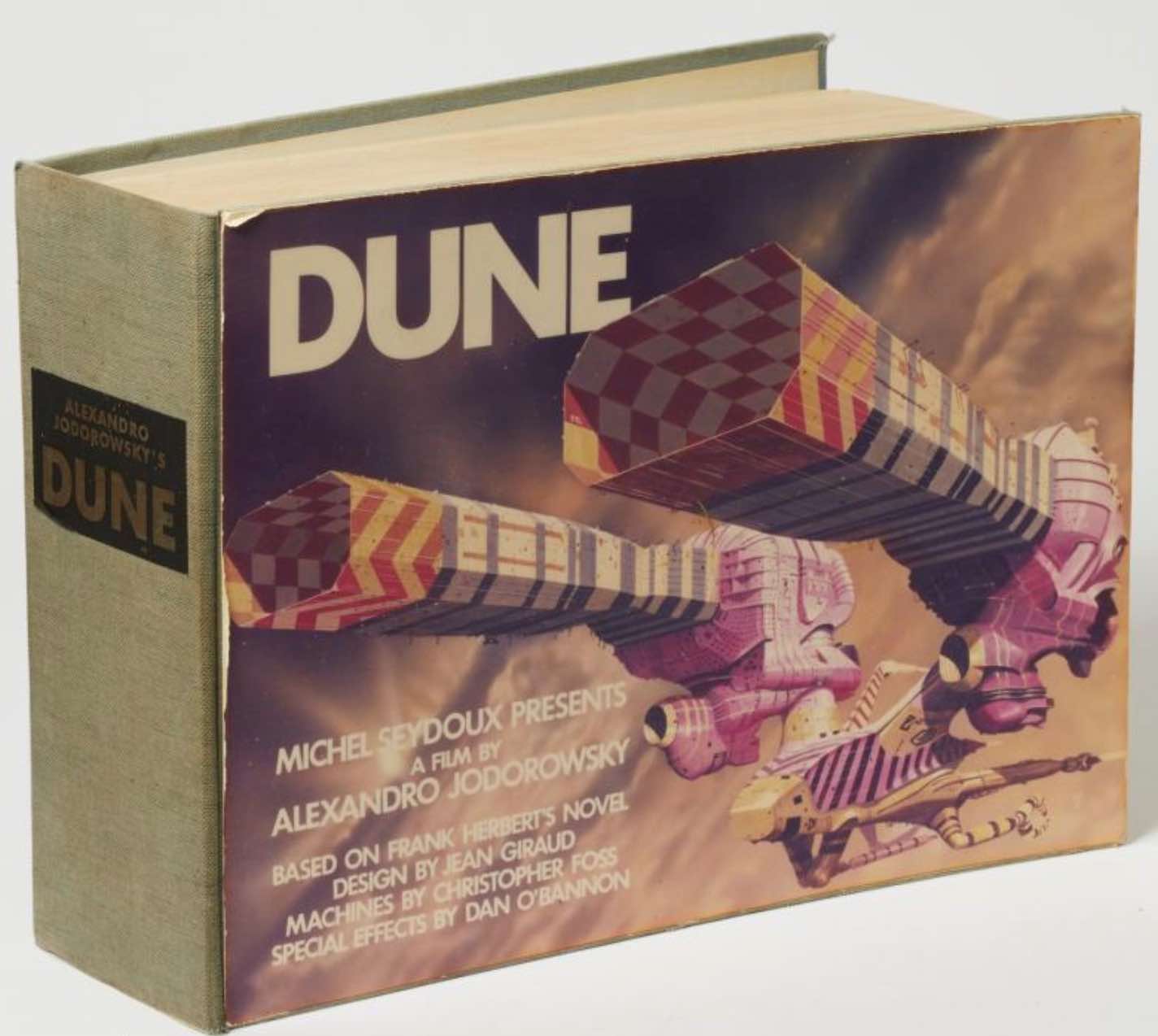

Alas, none of us will ever get to see Jodorowsky’s Dune, now one of the most storied of all unmade films. But one of us — one of the deep-pocketed among us, at least — now has a chance to own the book. Not Herbert’s novel: the book assembled circa 1985 as a pitching aid, meant to show studios the extensive pre-production work Jodorowsky, producer Michel Seydoux, and their collaborators had done.

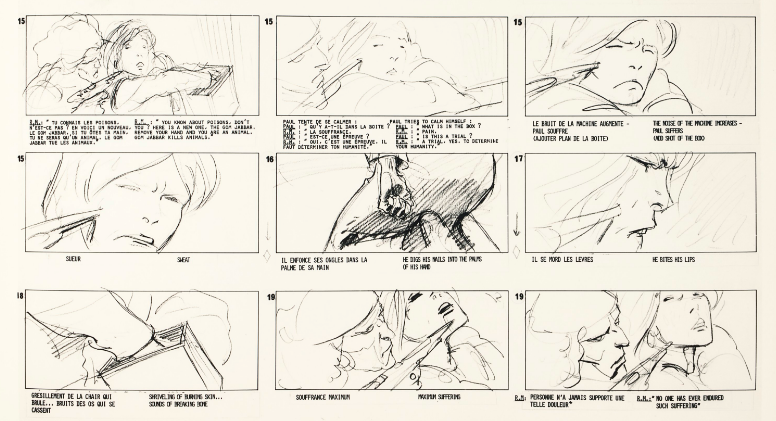

“Filled with the script, storyboards, concept art, and more, the book is basically as close as anyone can get to seeing Jodorowsky’s version of Dune,” writes io9’s Germain Lussier. “But, of course, the director and his team only created a handful of copies and this was decades ago. This isn’t a book you can just get on Amazon.”

But you can get it at Christie’s, on whose auction block it’s expected to go for between €25,000 and €35,000 (around USD $30,000–40,000). Reckoning that only ten to twenty copies were ever printed, the house’s listing describes the book as “an extraordinary artifact” from “a doomed project which inspired legions of film-makers and moviegoers alike.” Despite all of Hollywood ultimately passing on this enormously ambitious adaptation, “all of this was not in vain.” Jodorowsky himself claims that, though unrealized, his Dune set a precedent for “a larger-than-life science fiction movie, outside of the scientific rigor of 2001: A Space Odyssey.” Its influence, according to Christie’s, is present in 1970s films like Star Wars and Alien. Would it be too much to sense a trace of the Jodorowskyan in Villeneuve’s Dune as well?

Related Content:

Mœbius’ Storyboards & Concept Art for Jodorowsky’s Dune

Alejandro Jodorowsky’s 82 Commandments For Living

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the Substack newsletter Books on Cities, the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.